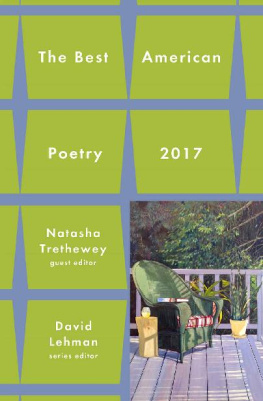

Copyright 2018 by Natasha Trethewey All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016. hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Trethewey, Natasha D., 1966 author. Title: Monument : poems : new and selected / Natasha Trethewey. Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018. Identifiers: LCCN 2018012255 (print) | LCCN 2018016439 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328508690 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328507846 (hardcover) Classification: LCC PS3570.R433 (ebook) | LCC PS3570.R433 A6 2018 (print) | DDC 811/.54dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018012255 Cover design by Mark R. Robinson Cover photograph Vincent Ruddy Author photograph Matt Valentine v1.1018 Invocation, 1926 by Natasha Trethewey, and Congregation and Liturgy from

Beyond Katrina by Natasha Trethewey, copyright 2010 by Natasha Trethewey, reprinted by permission of University of Georgia Press.

Limen, Early Evening, Frankfort, Kentucky, Family Portrait, Flounder, White Lies, Gathering, Picture Gallery, Domestic Work, 1937, Speculation, 1939, Secular, Signs, Oakvale, Mississippi, 1941, Expectant, Tableau, At the Station, Naola Beauty Academy, New Orleans, 1945, Drapery Factory, Gulfport, Mississippi, 1956, His Hands, Self-Employment, 1970, and Gesture of a Woman-in-Process copyright 2000 by Natasha Trethewey. Reprinted from Domestic Work with the permission of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, www.graywolfpress.org. Excerpt from Meditation on Form and Measure from Black Zodiac by Charles Wright. Copyright 1997 by Charles Wright. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. from The Great City, Walt Whitman

Imperatives for Carrying On in the Aftermath

Do not hang your head or clench your fists when even your friend, after hearing the story, says,

My motherwould never put up with that. Fight the urge to rattle off statistics: that, more often, a woman who chooses to leave is then murdered. from The Great City, Walt Whitman

Imperatives for Carrying On in the Aftermath

Do not hang your head or clench your fists when even your friend, after hearing the story, says,

My motherwould never put up with that. Fight the urge to rattle off statistics: that, more often, a woman who chooses to leave is then murdered.

The hundredth time your father says, But she hated violence,why would she marry a guy like that? dont waste your breath explaining, again, how abusers wait, are patient, that they dont beat you on the first date, sometimes not even the first few years of a marriage. Keep an impassive face whenever you hear Stand By Your Man, and let go your rage when you recall those words were advice given your mother. Try to forget the first trial, before she was dead, when the charge was only attempted murder; dont belabor the thinking or the sentence that allowed her ex-husbands release a year later, or the juror who said, Its a domestic issuethey should work it out themselves. Just breathe when, after you read your poems about grief, a woman asks, Do you thinkyour mother was weak for men? Learn to ignore subtext. Imagine a thought cloud above your head, dark and heavy with the words you cannot say; let silence rain down. Remember you were told, by your famous professor, that you should write about something else, unburdenyourself of the death of your mother and just pour your heart out in the poems. Ask yourself whats in your heart, that reliquaryblood locket and seedbedand contend with what it means, the folk saying you learned from a Korean poet in Seoul: that one does not bury the mothers bodyin the ground but in the chest, orlike youyou carry her corpse on your back.

I

fromDomestic Work

Limen

All day Ive listened to the industry of a single woodpecker, worrying the catalpa tree just outside my window. Hard at his task, his body is a hinge, a door knocker to the cluttered house of memory in which I can almost see my mothers face.

She is there, again, beyond the tree, its slender pods and heart-shaped leaves, hanging wet sheets on the lineeach one a thin white screen between us. So insistent is this woodpecker, Im sure he must be looking for something elsenot simply the beetles and grubs inside, but some other gift the tree might hold. All day hes been at work, tireless, making the green hearts flutter.

Early Evening, Frankfort, Kentucky

It is 1965. I am not yet born, only a fullness beneath the Empire waist of my mothers blue dress. The ruffles at her neck are waves of light in my fathers eyes.

He carries a slim volume, leather-bound, poems to read as they walk. The long road past the college, through town, rises and falls before them, the blue hills shimmering at twilight. The stacks at the distillery exhale, and my parents breathe evening air heady and sweet as Kentucky bourbon. They are young and full of laughter, the sounds in my mothers throat rippling down into my blood. My mother, who will not reach forty-one, steps into the middle of a field, lies down among clover and sweet grass, right here, right now dead center of her life.

Family Portrait

Before the picture man comes Mama and I spend the morning cleaning the family room.

She hums Motown, doles out chores, a warning He has no legs, she says. Dont stare. Im first to the door when he rings. My father and uncle lift his chair onto the porch, arrange his things near the place his feet would be. He poses our only portraitmy father sitting, Mama beside him, and me in between. I watch him bother the space for knees, shins, scratching air asyears laterId itch for whats not there. You bout as white as your dad,and you gone stay like that. Aunt Sugar rolled her nylons down around each bony ankle, and I rolled down my white knee socks letting my thin legs dangle, circling them just above water and silver backs of minnows flitting here then there between the sunspots and the shadows. This is how you hold the poleto cast the line out straight.Now put that worm on your hook,throw it out, and wait. She sat spitting tobacco juice into a coffee cup. This is how you hold the poleto cast the line out straight.Now put that worm on your hook,throw it out, and wait. She sat spitting tobacco juice into a coffee cup.

Hunkered down when she felt the bite, jerked the pole straight up reeling and tugging hard at the fish that wriggled and tried to fight back. A flounder, she said, and you can tellcause one of its sides is black.The other side is white, she said. It landed with a thump. I stood there watching that fish flip-flop, switch sides with every jump.

White Lies

The lies I could tell, when I was growing up light-bright, near-white, high-yellow, red-boned in a black place, were just white lies. I could easily tell the white folks that we lived uptown, not in that pink and green shanty-fied shotgun section along the tracks.

I could act like my homemade dresses came straight out the window of Maison Blanche. I could even keep quiet, quiet as kept, like the time a white girl said (squeezing my hand), Nowwe have three of us in this class. But I paid for it every time Mama found out. She laid her hands on me, then washed out my mouth with Ivory soap. Thisis to purify, she said, and cleanse your lying tongue. Believing her, I swallowed suds thinking theyd work from the inside out.