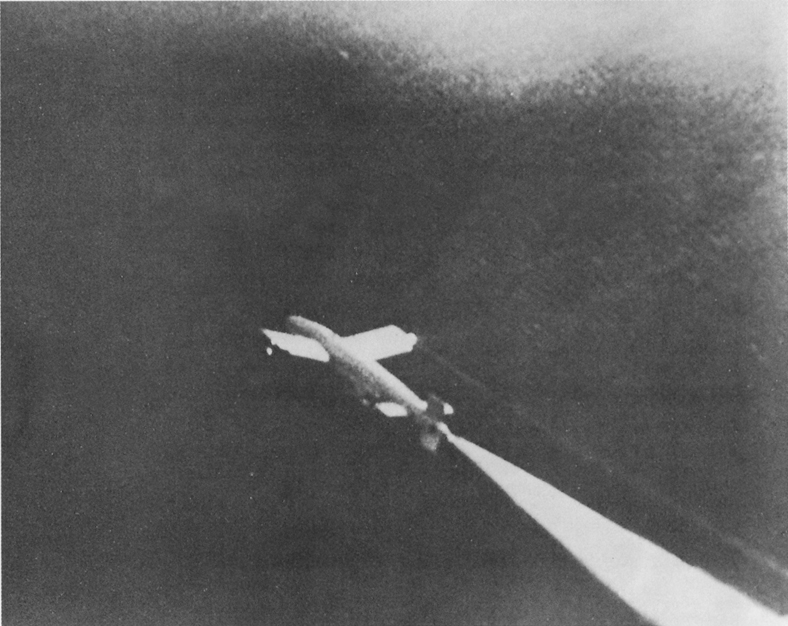

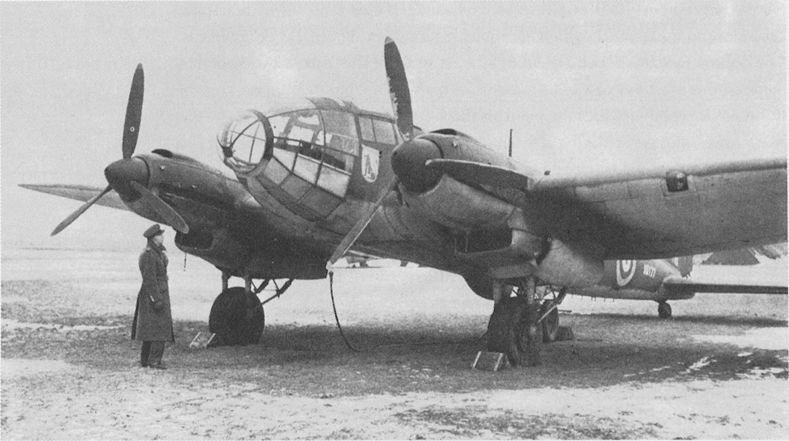

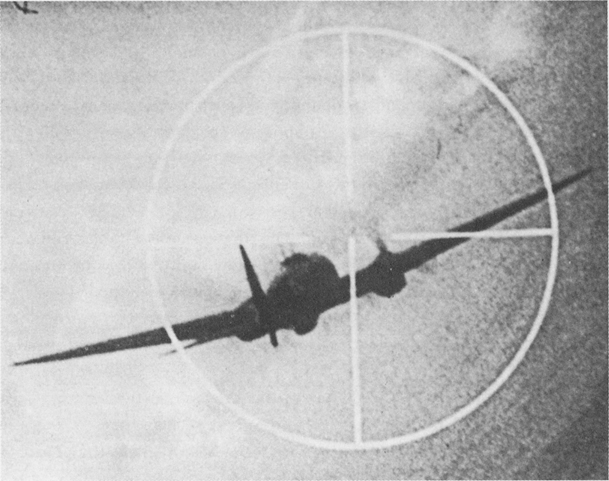

The Blohm und

Voss 143. One of

many guided

missiles developed

by the Germans

during the war, the

BV 143 was tested

in 1941 as a guided

aerial torpedo for

use against

shipping, but did

not enter

operational service.

First published in 1978 by The British Broadcasting Corporation

Published in 2004 in this format by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY CLASSICS

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley

S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Brian Johnson, 1978, 2004

ISBN 1 84415 102 6

The right of Brian Johnson to

be identified as Author of this Work has

been asserted by him in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book

is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage

and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Wharncliffe Local History, Pen & Sword Select,

Pen & Sword Military Classics and Leo Cooper

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

For all who worked in the small back rooms

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This book is based on the BBC Television Series The Secret War, and I am indebted to the researchers who gathered the material for the original six programmes upon which I have drawn heavily. Charmian Campbell researched The Battle of the Beams and Radar, interviewing many of the participants in Britain and Germany. Susan Bennett tracked down witnesses in Germany, Poland and France to uncover much of the Enigma story. Kate Haste combed the Public Records Office for information on the V1 and V2, in addition to interviewing many of the men and women involved.

My colleague Fisher Dilke, who wrote the television Enigma programme, greatly assisted with additional research in the preparation of the final chapter of the book.

I am indebted also to the Public Record Office for allowing Archive material to be quoted.

Finally I wish to place on record my indebtedness to Tony Kingsford and Paul McAlinden of BBC Publications for their sympathetic editing and presentation of the manuscript.

The British Consulate in Oslo.

INTRODUCTION: A LETTER FROM OSLO

On 19 September 1939 in a speech in Danzig Hitler boasted of fearsome secret weapons against which Germanys enemies would be defenceless. Confirmation of the development of at least some of that arsenal was soon to come from a most unexpected source Germany in what must rate as one of the most incredible windfalls even in the long history of espionage. In the small hours of 5 November 1939 a parcel was left on a window-ledge of the British Consulate in Oslo, in what was still neutral Norway. Addressed to the Naval Attach, it contained several pages of German typescript and a small electronic device which, when examined in London by Dr R. V. Jones, of Air Ministry Scientific Intelligence, proved to be an early proximity fuse for an anti-aircraft shell and was clearly included to authenticate the much more important typescript. Subsequently known as the Oslo Report, this set out the scope of German military scientific research, including such highly classified information as the identity of Peenemunde as an important research centre.

The Junkers 88, the Luftwaffes new secret wonder plane, the correspondent stated, was to be used as a high-speed dive bomber a fact unknown in Britain. He detailed German radar developments and confirmed that radar had been instrumental in directing fighters to a squadron of Wellington bombers that had been decimated on a raid on Wilhelmshaven. He explained the working of a German night-bomber radio aid, which later became known as the Y-Gerte and which was to figure in the soon-to-be-fought Battle of the Beams. The report also significantly outlined German rocket development.

The letter was simply signed A German scientist who wishes you well. His identity has never been established, but he must have been highly placed. In London many sceptics rejected the authenticity of the document, and others claimed it to be a plant a propaganda exercise to undermine moral. Jones did not subscribe to these views, considering the document to be genuine; indeed, he later said that during the few quiet moments of the war I used to turn up the Oslo Report to see what was coming next.

The Oslo Report was a clear warning that the war was to be a struggle as much between scientists as fighting men a war which Britain, uncharacteristically, was well placed to fight. This was due in no small measure to the decision taken in 1938 to compile a register of some 5000 scientists. Thus highly capable men from universities and industry were ready to form the nucleus of a formidable army that was to wage a strange electronic war of secrets.

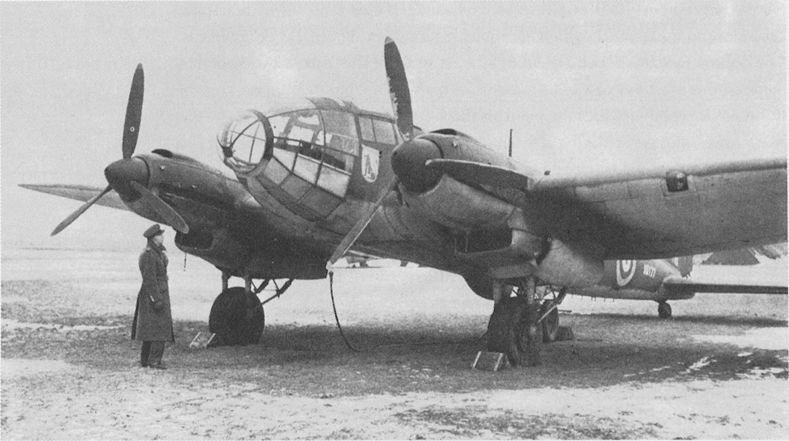

This He 111, forced down early in the war comparatively undamaged, was repaired and test-flown by the RAF. Although it carries RAF markings, it still retains the unit emblem of its late owners Kampfgeschwader 26. It was possibly from this machine that RAF Intelligence Officers salvaged the scrap of paper which gave the first clue to Knickebein whose aerials can be seen underneath the fuselage just to the left of the roundel.

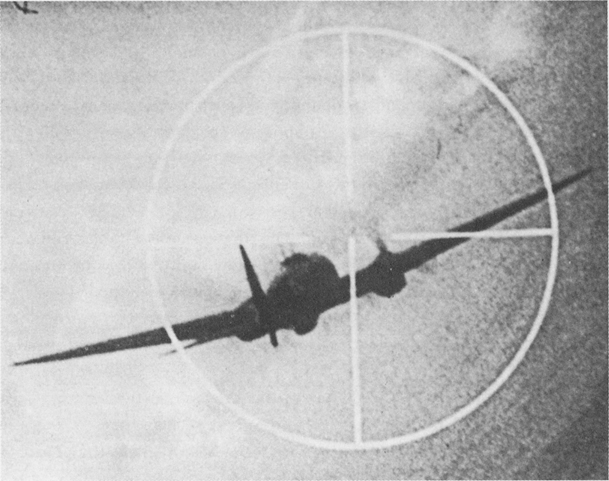

A fighter pilots view of an He 111. Like most German bombers in 1940, the Heinkels defensive armament was inadequate against Spitfires and Hurricanes. Although still handicapped then by lack of airborne radar, RAF night fighters nevertheless shot down several bombers on visual interception.

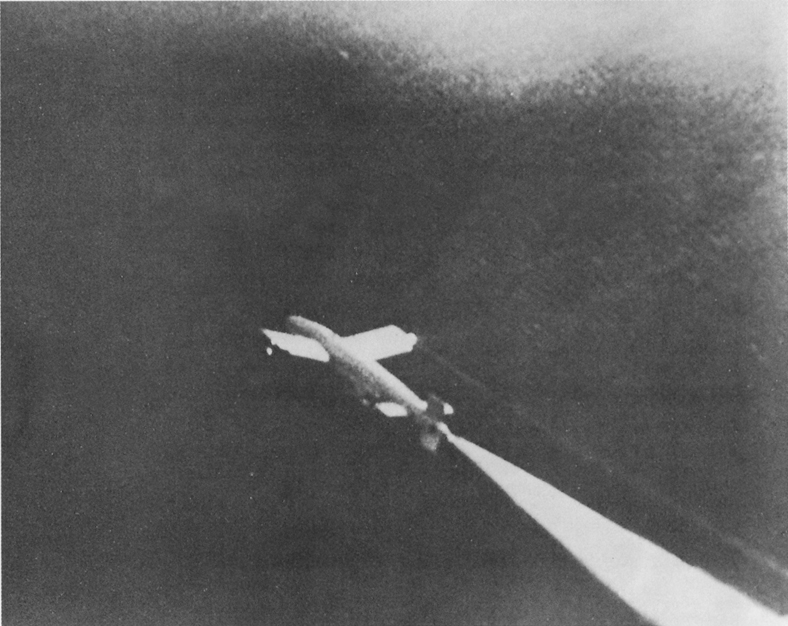

In the early months of 1940, the German Air Force, the Luftwaffe, began to fly night bombers over the blacked-out towns and countryside of Britain: not the massed formations that had been feared but single aircraft which appeared to be probing night defences which incidentally were at that time practically non-existent. However, one night in March 1940 one of these nocturnal wanderers, plotted by ground radar, was intercepted by a night fighter which made a lucky visual contact and shot it down.

The crashed aircraft, a Heinkel 111, bore the marking 1H + AC which identified its unit as Kampfgeschwader (Bomber Group) 26. It was, as a matter of routine, examined by RAF Technical Intelligence Officers; the examination must have been thorough, for salvaged from the wreckage was a scrap of paper which seemed to have been an aide-mmoire for the navigator. In translation it read:

Navigational aid: Radio Beacons working on Beacon Plan A. Additionally from 0600 hours Beacon Dhnen. Light Beacon after dark. Radio Beacon Knickebein from 0600 hours on 315.