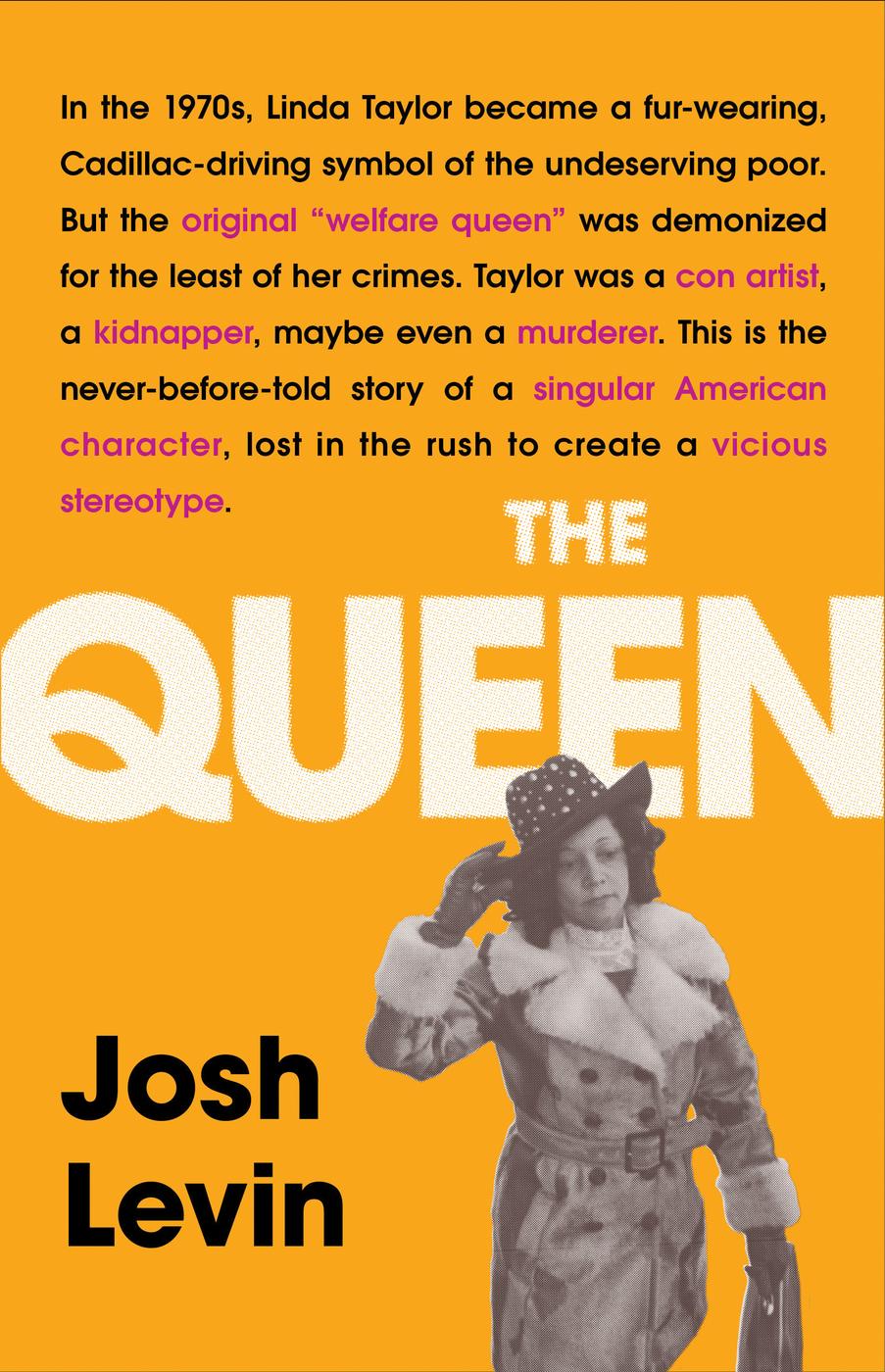

Copyright 2019 by Josh Levin

Cover photograph Bettmann/Getty Images

Author photograph by J. Seidman

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrown.com

twitter.com/littlebrown

facebook.com/littlebrownandcompany

First Edition: May 2019

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-51327-2

E3-20190426-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20190415-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20190325-DA-NF-ORI

E3-20190114-DA-NF-ORI

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

To Jess, for everything

How old was she? John Parks asked me. We were sitting outside on a spring day in 2013, a little less than thirty-eight years since his ex-wife, Patricia, had died under suspicious circumstances. Boy, you waited a long time to come, the seventy-seven-year-old Parks said, struggling to remember details, such as Patricias age, that had once seemed unforgettable. At first, it was just on the tip of my tongue. And nobody came.

Patricia Parks had been thirty-seven when she was pronounced dead of a barbiturate overdose on the night of June 15, 1975. Patricia, whod suffered from multiple sclerosis, had been treated at home by a friend whod promised to make her feel better. Linda Taylor submerged Patricia in ice-cold water and fed her medications stored in unlabeled bottles. Taylor also took possession of the sick womans house on the South Side of Chicago and became the executor of her estate. John Parks believed then and remained certain decades later that Taylor murdered Patricia. But nobody had seen fit to charge Taylor with his ex-wifes killing, and nobody in any position of authority, John told me, had bothered to ask him what he thought of Patricias friend. All they said was, Thats another black woman dead.

When I started digging into Linda Taylors life, I hadnt imagined that Id end up investigating a potential homicide. Taylor rose to prominence in the mid-1970s as a very different kind of villain: Americas original welfare queen. One of the first stories I ever read about her, a squib in Jet magazine from 1974, said that shed stolen $154,000 in public aid money in a single year, owned three apartment buildings, two luxury cars, and a station wagon, and had been busy preparing to open a medical office, posing as a doctor. Another Jet article depicted her as a shape-shifting, fur-wearing con artist who could change from black to white to Latin with a mere change of a wig. But when Ronald Reagan expounded on Taylor during his 1976 presidential campaign, shocking audiences with the tale of a woman in Chicago who used eighty aliases to steal government checks, he didnt treat her as an outlier. Instead, Reagan implied that Taylor was a stand-in for a whole class of people who were getting something they didnt deserve.

The words used to malign Linda Taylor hardened into a stereotype, one that was deployed to chip away at benefits for the poor. The legend of the Cadillac-driving welfare queen ultimately overwhelmed Taylors own identity. After getting convicted of welfare fraud in 1977, Taylor disappeared from public view and public memory. No one seemed to know whether shed really lived under eighty aliases, and nobody had any idea whether she was alive or dead.

I spent six years piecing together Taylors story and trying to comprehend why it got lost in the first place. The more I learned about her, the more the mythologized version of Linda Taylor fell apart, and not in the ways I expected. As a child and an adult, Taylor was victimized by racism and deprived of opportunity. She also victimized those even more vulnerable than she was.

Patricia Parkss death was a blip for the Chicago Tribune; Linda Taylors public aid swindle was a years-long obsession. For journalists and politicians, the welfare queen was a potent figure, a character whose outlandish behavior reliably provoked outrage. Poor black women saw their character assailed by association with Taylor. At the same time, a woman whom Taylor had preyed on elicited no sympathy. Patricia Parkss ex-husband, John, who died in 2016, believed that his familys race was the reason that Patricias death wasnt seen as a scandal or a tragedy. Id have to be somebody, he told me, explaining why some Americans get justice and others dont.

Linda Taylor did horrifying things. Horrifying things were also done in Linda Taylors name. No ones life lends itself to simple lessons and easy answers, and Taylors was more complicated than most. Ive tried my best to tell the whole truth about what Linda Taylor did, what she came to signify, and who got hurt along the way. That goal may be unattainable, but we do far more damage to the world and to ourselves when we dont care to pursue it.

Jack Sherwin tossed his days work on the front seat of his unmarked Chevy. Hed fished five or six burglary reports from his pigeonhole after roll call, enough to keep him and his partner occupied all morning and for a good chunk of the afternoon. Sherwin didnt need any more assignmentshe had at least a half-dozen more reports jammed inside his briefcase.

The Chicago burglary detective turned on the police scanner and peeled off his sport coat. August 12, 1974, was sunny, hot, and unbearably humid; the sky felt heavy but it wouldnt rain all day. Sherwin headed east from his units headquarters on Ninety-First Street and South Cottage Grove, past the Jewel Food Store where a group of armed men had recently made off with a $1,000 haul.

He parked his car in South Chicago, a working-class, mostly black and Latino neighborhood bordered on the west by the Skyway, a toll road that carried suburban commuters above a part of town theyd rather not drive through. A month earlier, a sixty-six-year-old woman had been shot in the neck a short distance away in Calumet Heights, on the street outside St. Ailbes Catholic church.more than four decades later, still the most homicides in a calendar year in the history of Chicago.

Sherwin wasnt dealing with anything as messy as a murder case. This was a routine burglary, not a big enough deal to justify his partner, Jerry Kush, getting out of the car.

The two-story, six-unit brick building at 8221 South Clyde Avenue looked like a tiny castle, with a crenellated roof, an arch over the entryway, and limestone ornaments near the windows. Sherwin rang the bell and got buzzed inside. As he knocked on the door of a first-floor apartment, he looked down at his clipboard and rehearsed a sequence of well-worn questions: Whats missing? Did anyone see what happened? Is there anything youd like to add to your original report?

![T.L. Taylor [T.L. Taylor] - Watch Me Play](/uploads/posts/book/131712/thumbs/t-l-taylor-t-l-taylor-watch-me-play.jpg)