About the Author

Sir Christopher Frayling is perhaps the most wide-ranging cultural historian of our times: the author of numerous publications on subjects ranging from vampires to Westerns; the writer and presenter of successful television series, whether on advertising, the Middle Ages or Tutankhamun. He is a Fellow of Churchill College, Cambridge, and was Rector of the Royal College of Art, London, from 1996 to 2009, where he remains Professor Emeritus of Cultural History. His many public appointments have included Chairman of Arts Council England; Chairman of the Design Council; and the longest-serving Trustee of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Chinese Lives: The People who Made a Civilization

The Seventy Wonders of China

Chinese Graphic Design in the Twentieth Century

Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged

High Society: Mind-Altering Drugs in History and Culture

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

Contents

Yellow Peril

1: a danger to Western Civilization held to arise from expansion of the power and influence of Oriental people;

2: a threat to Western living standards developed through the incursion into Western countries of Oriental labourers willing to work for very low wages and under inferior working conditions.

Websters New International Dictionary, 1971

If there were no more than twenty Chinese people dwelling in Chinatown, the accounts of the sensation-seekers would without fail magnify their number to five thousand. And every one of those five thousand yellow-faced demons will smoke opium, smuggle arms, commit murder hiding the corpses under their bed rape women regardless of age and commit an endless amount of crimes, all deserving, at the very least, gradual dismemberment and death by ten thousand slices of the sword. Authors, playwrights and screenwriters are prompt to base their pictures of the Chinese upon such rumours and reports

Lao She: Mr Ma and Son, first published in China, 1929; Penguin translation

by William Dolby, 2013

Aladdins Procession, from Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp, set in an imaginary China as was traditional, illustrated by Walter Crane (1874). Buyenlarge/SuperStock.

The seeds of this book were first sown over a genial lunch with Edward Said in Paris on 7 July 1995. We had been discussing the cinema of Empire in the context of postcolonial ideas, for , then our discussion turned to Saids very influential book on Orientalism (1978), one of the few academic studies to have changed the meaning of a word in common parlance in this case, from description of a specialism to a pejorative. I suggested that there were two very significant gaps in Orientalism: any analysis of the role of popular culture in diffusing (or even creating) orientalist prejudices and reinforcing stereotypes, and any case-studies from or about China. Saids main interest, it seemed, was confined to academic writing by intellectuals in serious literature/high culture, and to the Middle East and North Africa. He tended to see high-table orientalists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries especially those from France and Britain as the main culprits, busy projecting their own parochial assumptions and racist myths onto the Orient through their specialist writings, which would then somehow trickle down, or so it was implied, into popular culture.

Edward Said readily agreed with the point about the absence of popular culture in Orientalism, most notably film:

there is definitely a connection of some sort between the mass media, literature and serious novels. And the mass media, certainly the films, have a much more powerful, simplifying and reductive effect. Because they are visual. I mean, when you see an American-Indian with feathers and paint across his face he looks terrifying and it doesnt matter whether youve read about him in Fenimore Cooper or not it fixes the image in your mind forever. It also, if you receive these as I did growing up medieval films about the Crusades, Arabian Nights films, Imperial films, films with exotic Chinese all of them are very difficult to remove from your head when later on you grow up and you read the books.

Someone ought, he said, seriously to examine the diffusion of orientalism in his view usually originating in academe through the media of popular and mass culture, and to question whether such ideas ever originated there: pulp literature, song lyrics, comics, films, cartoons, postcards, melodrama, music hall and pantomime. There had been a few studies of this kind, but nothing really substantial. Maybe I would be interested in taking on such a project?

He agreed with the point about China as well. Some of the most indelible visual images from popular culture were of Chinamen.

I remember their effect on me [when growing up in Egypt and British Palestine], the Fu Manchu films and Charlie Chan We just didnt know. We didnt interact with Chinese people. So in a certain way these films also created divisions within the non-European world. But the most powerful thing about them is that they established the norm, which became unquestioning. And everything else was deviant, frightening and eccentric. They were and are very strong

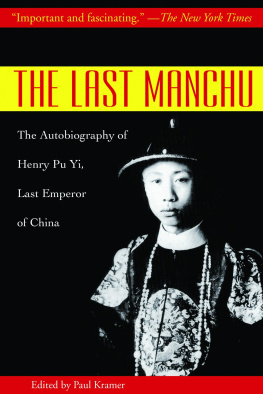

There was much to be written about the assumptions of sinologists in the Victorian and Edwardian periods, their defence of their own guilty consciences, and about the received wisdom among connoisseurs that the ancient glories of Chinese culture peaked in the Tang dynasty around the seventh and eighth centuries and had been in decline ever since; about how the wonderment of Marco Polo in Cathay morphed into the contempt of the nineteenth century and beyond; about how it was thought to have been the Jesuits and European administrators who prevented the savage Genghis Khan tendency from resurfacing.

In America, the literary image of the Chinese as alien other as sinister villain or dragon lady or comic laundryman or threatening heathen or broken blossom or doomed prostitute or member of a brutalized horde grew out of Bret Harte, mining stories from gold-rush California, railroad and urban myths about bachelor societies, the Exclusion Act of 1882, and the anxieties the images embodied were mainly about immigration. In Britain and the rest of Europe, however, the repertoire of Chinese characteristics also reflected anxieties about the decline of Empire and the rising dragon. The stories were about us they were not really about China at all. By the time Edward Said first encountered them, during his schooldays in Cairo, British occupation was nearing its end and Arab Nationalism was on the rise:

When I was growing up in the early 1940s, I must have been six or seven, and seeing films such as Gunga Din, The Lives of a Bengal Lancer and The Four Feathers, there were no comparably powerful images yet being produced in the Egyptian cinema no costume dramas, nothing exotic, only films about local Egyptian life. I dont remember ever seeing any of these films in the framework of colonialism in which I was on the side of the colonized. Rather I saw them as a kind of replica of the schools I went to which happened to be English schools where the master looked like those guys in the films, the leading characters. Gunga Din looked like a recalcitrant schoolboy who had his moment of glory at the end, his apotheosis. That was the best you could do. There wasnt a moments doubt that I should question any of this. It was the height of sportsmanship, of behaving well those are the words we used. Sacrificing yourself for