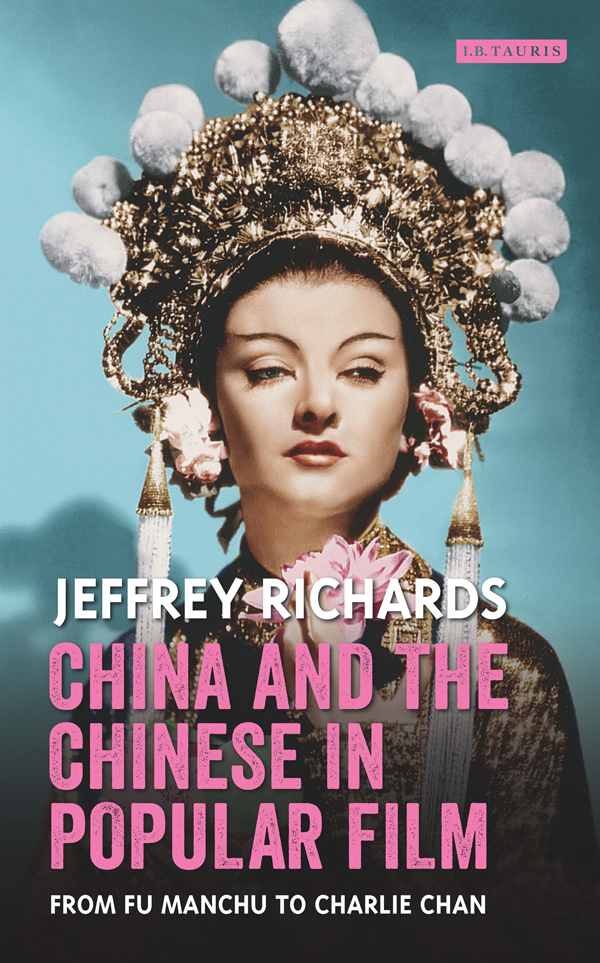

Jeffrey Richards is Emeritus Professor of Cultural History, Lancaster University. His many publications on cinema and its history include The Age of the Dream Palace: Cinema and Society in 1930s Britain; Best of British: Cinema and Society from 1930 to the Present; the British Film Guide to A Night to Remember (all I.B.Tauris); and Mass Observation at the Movies. He is General Editor of I.B.Tauris Cinema and Society Series.

Jeffrey Richards latest book is a characteristically wide-ranging, thorough and richly detailed study that sheds new light on both familiar classics and forgotten films. Informative and accessible, China and the Chinese in Popular Film will appeal to specialist and non-specialist readers alike.

Mark Glancy, Reader in Film History, Queen Mary University of London

China and

the Chinese

in Popular

Film

From Fu Manchu to Charlie Chan

Jeffrey Richards

Published in 2017 by

I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

London New York

www.ibtauris.com

Copyright 2017 Jeffrey Richards

The right of Jeffrey Richards to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

ISBN: 978 1 78453 720 3

eISBN: 978 1 78672 064 1

ePDF: 978 1 78673 064 0

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

Contents

List of Illustrations

Boris Karloff in The Mask of Fu Manchu (MGM, 1932)

Christopher Lee in The Face of Fu Manchu with Tsai Chin (Anglo-Amalgamated, 1965)

One of many Fu Manchu clones: Joseph Wiseman as Dr No with Sean Connery and Ursula Andress (United Artists, 1962)

Myrna Loy as Fah Lo Suee in The Mask of Fu Manchu (MGM, 1932)

Anna May Wong (publicity photograph, 1935)

The opium den in Broken Blossoms (United Artists, 1919)

Luise Rainer and Paul Muni in The Good Earth (MGM, 1937)

Barbara Stanwyck and Nils Asther in The Bitter Tea of General Yen (Columbia, 1933)

Paul Lukas and Kay Walsh in The Chinese Bungalow (British Lion, 1940)

Gregory Peck and Richard Loo in The Keys of the Kingdom (20th Century-Fox, 1944)

Richard Todd defying Communists in Yangtse Incident with Richard Leech and Keye Luke (British Lion, 1957)

Clifton Webb and William Holden defying Communists in Satan Never Sleeps (20th Century-Fox, 1962)

David Niven defying the Chinese Empress (Flora Robson) in 55 Days at Peking (Rank-Bronston, 1962)

Warner Oland as Charlie Chan (publicity still, undated)

Sidney Toler as Charlie Chan (Monogram, 1945)

Acknowledgements and Note on Chinese Names

This book has been many years in the making and I have had the opportunity of honing various chapters in lectures given in a variety of institutions. But I also owe debts of gratitude to many individuals for help and advice of different kinds and would like to thank in particular Robert Bickers, James Chapman, Mark Glancy, Joel Hockey, Linda Persson, Anthony Slide, Richard Taylor, Deborah Williamson, Anne Witchard and Peter Yeandle. Thanks are due to Jane Robson for her copy-editing and to Zoe Ross for compiling the index. Two long-standing friends have been especially helpful, Sir Christopher Frayling and Professor Kevin Harty, and I dedicate the book to them.

Throughout I have used the Wade-Giles system for the Romanisation of Chinese names rather than the pinyin system which has replaced it, because it was the Wade-Giles system which operated during the period under review. Similarly, where the terms Oriental and Asiatic are used they reflect the prevalent contemporary usage at the time the films were made. All stills are from the authors collection.

For

Sir Christopher Frayling

and

Kevin Harty

Western Attitudes to China and the Chinese

The oldest and most enduring image of China and the Chinese in the West is of numberless yellow hordes swarming out of the East to engulf Western civilisation. This constituted a folk memory and derived directly from the eruption in the thirteenth century of the Mongol armies, led by the grandson of Genghis Khan, who appeared suddenly from the mysterious heart of Asia and rampaged through Russia, Eastern and Central Europe before being halted at the gates of Vienna in 12412. It lurked in the collective consciousness to be reawakened periodically by events such as the Taiping Rebellion, the Boxer Uprising and the Korean War which were seen and reported in the language of vast and apparently unstoppable hordes.

A more positive image emerged from the narratives of Western travellers to China in the later medieval and Renaissance periods, the Italian Marco Polo, Spanish and Portuguese travellers, Franciscan friars and Jesuit missionaries. They reported on a peaceful, prosperous and well-ordered empire with a modest, hard-working and law-abiding population. But a darker side to the civilisation surfaced in reports of slavery, footbinding, female infanticide and the castration of male children to create eunuchs, tales which created a belief in a tendency to cruelty as an inherent character trait of the Chinese. Sinophilia reached a zenith in the eighteenth century, particularly in France, with admiration and imitation of the style dubbed Chinoiserie which embraced items such as blue and white porcelain, ornamental pagodas and pavilions, lacquered furniture, Chinese lanterns, Chinese screens, Chinese wallpaper and embroidered silk, and in the celebration of an idealised Chinese Empire which was utilised as a means of critiquing contemporary Western society.

This all changed in the nineteenth century in the context of the rapid and apparently irreversible development of European empires and the transformation of Western society by the industrial revolution. Apart from the enclaves of Macao and Hong Kong, China never became part of the formal European empires but it was integral to an informal imperialism based on Western trade and commerce. The European powers, in particular the British, took up residence in Shanghai and the so-called treaty ports and participated in the Imperial and Maritime Customs service, which was the principal source of revenue for the Chinese imperial government, and which was run by a succession of Britons.

Compared to the dynamic and expanding European empires, China came to seem stagnant, backward, hidebound and firmly opposed to progress and innovation, its government system corrupt, sclerotic and autocratic, its people cruel, cunning, superstitious and xenophobic. The horrors of the Indian Mutiny, graphically reported in a rabidly racist press, had instilled a generalised fear of Asiatics in the Western population and this was apparently confirmed by the Boxer Rebellion and the siege of the foreign legations in Peking in 1900. As Paul A. Cohen has written of the Boxers: In film, fiction and folklore, they functioned over the years as a vivid symbol of everything we most detested and feared about China.