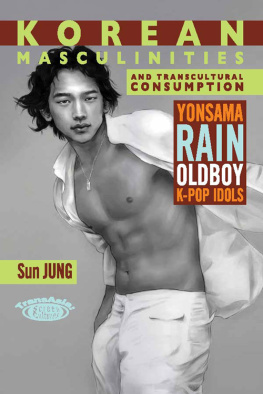

Chinese Fans of Japanese and Korean Pop Culture

How can Japanese popular culture gain nerous fans in China, despite pervasive anti-Japanese sentiment? How is it that theres such a strong anti-Korean sentiment in Chinese online fan communities when the official Sino-Korean relationship is quite stable before 2016? Avid fans in China are raising hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding to make gifts to their idols in foreign countries. Tabloid reports on Japanese and Korean celebrities have been known to trigger nationalist protests in China. So, what is the relationship between Chinese fandom of Japanese and Korean popular culture and nationalist sentiment among Chinese youth?

Chen discusses how Chinese fans of Japanese and Korean popular culture have formed their own nationalistic discourse since the 1990s. She argues that, as nationalism is constructed from various entangled ideologies, narratives, myths and collective memories, popular culture simply becomes another resource for the construction of nationalism. Fans thus actively select, interpret and reproduce the content of cultural products to suit their own ends. Unlike existing works, which focus on the content of transnational cultural flows in East Asia, this book focuses on the reception and interpretation of the Chinese audience.

Lu Chen is assistant professor in the Faculty of Journalism and Communication, Guangzhou University, China.

Routledge Contemporary China

For our full list of available titles www.routledge.com/Routledge-Contemporary-China-Series/book-series/SE0768

173Public Security and Governance in Contemporary China

Mingjun Zhang and Xinye Wu

174Interest Groups and New Democracy Movement in Hong Kong

Edited by Sonny Shiu-Hing Lo

175Civil Society in China and Taiwan

Agency, Class and Boundaries

Taru Salmenkari

176Chinese Fans of Japanese and Korean Pop Culture

Nationalistic Narratives and International Fandom

Lu Chen

177Emerging Adulthood in Hong Kong

Social Forces and Civic Engagement

Chau-kiu Cheung

178Citizenship, Identity and Social Movements in the New Hong Kong

Localism after the Umbrella Movement

Edited by Wai Man Lam and Luke Cooper

179The Politics of Memory in Sinophone Cinemas and Image Culture

Altering Archives

Edited by Peng Hsiao-yen and Ella Raidel

180Chinas Soviet Dream

Propaganda, Culture, and Popular Imagination

Yan Li

Chinese Fans of Japanese and Korean Pop Culture

Nationalistic Narratives and International Fandom

Lu Chen

First published 2018

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2018 Lu Chen

The right of Lu Chen to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-1-138-21969-4 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-41473-7 (ebk)

Typeset in Galliard

by Apex CoVantage, LLC

On April 9, 2006, after the State Administration of Radio, Film and Television (SARFT) launched a new policy to prohibit foreign animation from being broadcasted during prime time (1700 to 2000), Lin Hua (alias), a college student, planted a fake bomb in Beijings biggest bookshop. With that, Lin demanded that the bookshop sell Japanese movies instead of Chinese cartoon products or he would activate the bomb. In court, Lin criticised the Chinese governments policy against foreign animation (Endo, 2008). An internet survey on

Lins case appears to reflect, to some extent, that some Chinese youth are more open-minded about foreign cultures, even though supposedly they should boycott cultures such as that of the Japanese for historical reasons and the rising anti-Japanese sentiment since 2005. Yet, meanwhile, on June 9, 2010, around 100,000 netizens made a spam attack on the fan websites of Korean pop (K-pop) group Super Junior because their fans caused riots at the Shanghai Expo. The netizens proclaimed their online attacks as a Holy War. They also hacked into Korean government-owned websites. From these incidences, we see two extreme responses to foreign popular culture.

These two cases reveal the complex relationship between the reception of foreign popular culture and the formation of nationalistic sentiment among Chinese youth growing up in the reform era. The young fans of foreign popular culture, whose attitudes and experience of nationalism have been understated in previous studies, neither embrace foreign culture unconditionally nor resist globalisation with patriotism and xenophobia. Nationalism is certainly a more complex topic than that and to tease out a more sophisticated understanding on Chinese nationalism in the new century, the nationalistic sentiments found in Chinese fandom for Japanese and Korean popular culture can provide us with an opportunity for a better understanding of such development. Briefly, the research question of this book is how Chinese fans of Japanese and Korean popular culture have formed their own nationalistic discourse since the 1990s. In the following chapters, I will be analyzing the nationalistic discourse constructed by fans through the role of fan production and reception of culture. points out some recent dynamics in the changing interaction between fan culture and nationalism among Chinese youth.

Notes

. Retrieved on November 18, 2008.

.

The term popular culture first came into use in the English language in the early-nineteenth century. Popular is derived from the Latin to mean belonging to the people, which draws distinctions between the views of the people and those who would wield power over them. The term held negative connotations at the time of industrialisation because the elites felt their culture was threatened by this working-class popular culture. Before the 1980s, studies on popular culture focused on the potential harm it could have to democratic participation and cultural uniqueness (Clark, 2010, p. 422).

Hall argued that there is an opposition between what belongs to the central domain of the elite and the culture of the people. This opposition constantly structures the domain of culture into the popular and non-popular which is why the persistent tension to dominant culture is essential in defining popular culture (Hall, 2010, p. 220).