ABOUT THE AUTHOR

I AN U RBINA, is a reporter for The New York Times, based in the papers Washington bureau. He has degrees in history from Georgetown University and the University of Chicago, and his writings, which range from domestic and foreign policy to commentary on everyday life, have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, The Guardian, Harpers Magazine, and elsewhere. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife, son, stepdaughter, and a nuisance of a dog.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to the many people who were willing to reveal themselves to me in all their creative, petty, and vindictive glory. I would never have found them all were it not for Sahar Habibis speedy legwork and smart research. Mark Thomas and Gunnar Hellekson were also constant sources of good ideas. I am grateful to Christy Fletcher, my agent, for nimbly getting the project started and to Paul Golob, my editor at Times Books, for forcefully steering it on its wayalways with good humor and careful dedication. None of it would have been possible without Alex Wards careful diplomacy and smart editorial input. The hustle and creativity of the team at Henry Holt and Company was equally invaluable.

Thanks especially to Susan Edgerley and Joe Sexton, my bosses at The New York Times, for giving me the time I needed and the support I could never have expected. My gratitude goes to Wendell Jamieson, who worked his standard magic on my prose in the original piece. I also appreciate Kevin Flynn for tireless mentorship and Gerry Mullany for constantly being so flexible.

Most especially, thanks go to Sherry and Amanda for sharing with me a perspective on the world and for picking up so much slack as I try to offer a piece of this perspective to others.

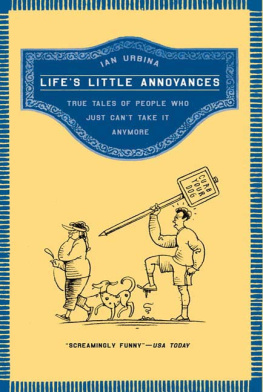

WHAT CAN YOU DO WHEN THE WORLD IS PUSHING YOU OVER THE EDGE?

MORE THAN YOU THINK

For some of us, its the automated voice that answers the phone when wed rather talk to a real person. For others, its the fact that Starbucks insists on calling its smallest-sized coffee tall. Or perhaps its those pesky subscription cards that fall out of magazines. Whatever it is, each of us finds some aspect of everyday existence to be particularly maddening, and we often long to lash out at these stubborn irritants of modem life.

In Lifes Little Annoyances. Ian Urbina chronicles the lengths to which some people will go when they have endured their pet peeves long enough and are not going to take it anymore. It is a compendium of human inventiveness, by turns juvenile and petty, but in other ways inspired and deeply satisfying. We meet the junk mail recipient who sends back unwanted business reply envelopes weighted down with sheet metal, so the mailers will have to pay the postage. We commiserate with the woman who was fed up with the colleague who kept helping himself to her lunch cookies, so she replaced them with dog biscuits that looked like biscotti. And we revel in the seemingly endless number of tactics people use to vent their anger at telemarketers, loud cell-phone talkers, spammers, and others who impose themselves on us.

A celebration of the endless variety of passive-aggressive behavior, Lifes Little Annoyances will provide comfort and inspiration to anyone who has ever gritted his teeth and dreamed of sweet retribution against the slings and arrows of outrageous people.

IAN URBINA is a reporter for The New York Times, based in the papers Washington bureau. He has degrees in history from Georgetown University and the University of Chicago, and his writings, which range from domestic and foreign policy to commentary on everyday life, have appeared in the Los Angeles Times.The Guardian. Harpers Magazine , and elsewhere. He lives in Washington, D.C., with his wife, son, stepdaughter, and a nuisance of a dog.

FROM

LIFES LITTLE ANNOYANCES

Chris Myers is thankful that he grew up next to a parking lot. His favorite childhood prank is serving him well in dealing with annoying people.

Whenever someone parks in a space reserved for the disabled, he leaves a note on the windshield that says, Im so sorry I hit your car. It doesnt look like the damage was severe. Then he signs a name but he makes it just messy enough to be illegible.

It works best if the person owns a fancy car, says the thirty-one-year-old student at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. The driver scrambles around trying to find the damage, and then theyre also faced with the decision of whether to call and report it to the police even though they are parked in an illegal space.

And if he is feeling particularly perverse, Myers adds a phone number to the note.

The best is to use a phone number for a group that advocates on behalf of the disabled, he says.

1

WEAPONS OF THE WEAK

It makes no sense that inconsiderate dog owners refuse to clean up after their pets, so why should the response be any more rational? If a person risks getting shot by taking the logical approach to dealing with impatient drivers who lay on their horns for no apparent reason, then why not try a softer, and perhaps less reasonable, tactic? |

The world would be an awfully boring place if everyone acted logically. And justice would only belong to the litigious. |

Thankfully, there are people who occupy the space just below aggression but just above following the rules. |

So when our favorite TV program is interrupted by yet another fund-raising telethon, its these types who call in to unnerve the smiling phone attendants seated in front of the cameras. And when every waiting room on the planet seems to have a television blaring some mind-numbing talk show, these people bring us the perfect tool to shut them off without anyone knowing who did it. |

They are the arms dealers and foot soldiers of lifes smallest battles. And we all owe them a debt of gratitude. They make the world safe for the rest of us who are equally frustrated but just a little more timid. |

WHO TURNED THIS THING ON, ANYWAY?

Nothing tortures the psyche more than being trapped in a room with the voice of Geraldo Rivera lecturing about the decline of American culture. And no matter how hard you try to look away from that television in the hospital waiting room or the airport lobby, the babbling entrances you like the rest of the zombies sitting around.

If only you could turn it off without causing a minor uproaror at least without anyone knowing it was you who did it.

All Mitch Altman wanted to do that day was catch up with several friends he met for dinner. The whole point was for us to share each others company, says the forty-eight-year-old inventor, who lives in San Francisco.

But the televisions perched in the corners of the Chinese restaurant were monopolizing attention. No one could focus back on each other, Altman says.

When Altman and his friends finally did reclaim control of their attention, the conversation quickly drifted to the topic of public television sets. All agreed that a discreet and universal remote would be the ultimate weapon against this pervasive annoyance.

So Altman built one. And after testing it out at a couple of local bars and restaurants, he named his pocket-sized gadget TV-B-Gone and began selling it on the Internet.

The choice of having that distraction on or not should be yours, he says. Now, it cant be taken for granted that everyone wants the television blaring.

Of course, his weapon cuts both ways. It has only one button, Altman explains. Unfortunately, that means it works as well to turn on the TV as it does to turn it off.