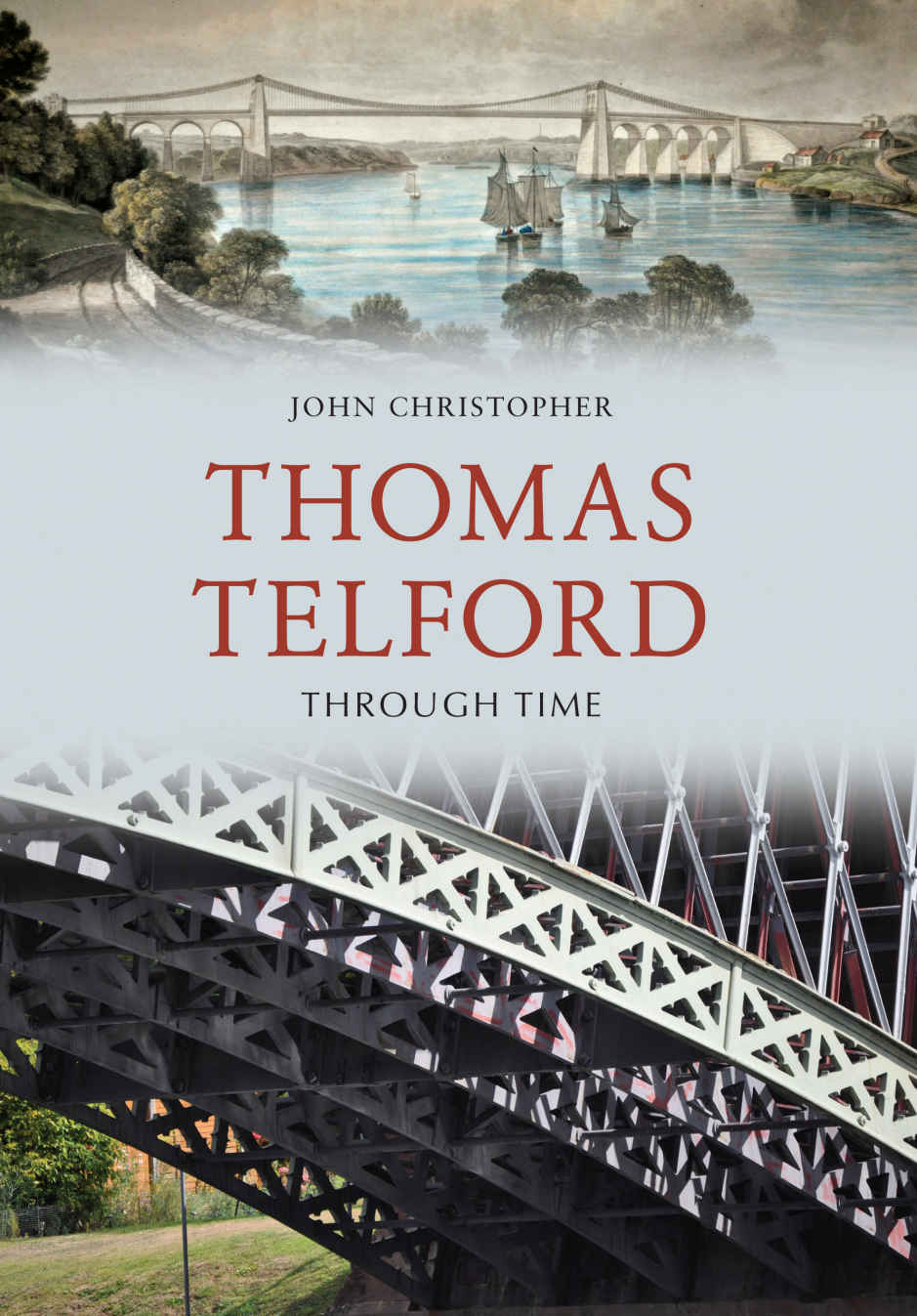

A highly romanticised view of Telfords suspension bridge at Conwy, completed in 1826. It is shown before the addition of Stephensons tubular rail bridge and the much later modern road bridge. See .

About this book

The illustrations in this book encourage the reader to explore many aspects of Telfords works. They seek to document not only their history, their architecture and the changes that have occurred over the years, but also record something of the day-to-day life of these structures. Hopefully they will encourage you to delve a little deeper when exploring the life and work of Thomas Telford, and the good news is that most locations have good public access.

First published 2016

Amberley Publishing

The Hill, Stroud

Gloucestershire, GL5 4EP

www.amberley-books.com

Copyright John Christopher, 2016

The right of John Christopher to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 9781445657813 (PRINT)

ISBN 9781445657820 (eBOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in 9.5pt on 12pt Celeste.

Typesetting by Amberley Publishing.

Printed in the UK.

Table of Contents

The Colossus of Roads

Telfords is a happy life: everywhere making roads, building bridges, forming canals and creating harbours works of sure, solid, permanent utility; everywhere employing a great number of persons, selecting the most meritous, and putting them forward in the world, in his own way.

Robert Southey

Without question Thomas Telford was the greatest engineer of his times; the most eminent of the pre-Victorian engineers (he died almost three years before Queen Victoria ascended to the throne). This was the era when the industrial revolution gave the engineers new materials, such as wrought and cast iron, to build with, but it was also the time when canals represented the future of transportation and the steam locomotive had yet to come into its own.

Telford was born in 1757 in the parish of Westerkirk in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. After leaving school he was apprenticed to a stonemason and as he mastered his craft the scope of his work increased. In 1782, at the age of twenty-five, he made his way to London where he was introduced to the architects Sir William Chambers and Robert Adam and they employed him as a stonemason on the new Somerset House. This experience nurtured his interest in architecture as a future career, which in turn led to an invitation from Sir William Pulteney, the Member of Parliament for Shrewsbury, to make improvements to Shrewsbury Castle. The Shrewsbury connection brought further commissions and, most importantly, in 1787 he was employed as the Surveyor of Public Works for Shropshire. As surveyor for the county Telford was also responsible for bridges and in 1790 he built the stone bridge across the Severn at Montford, the first of some forty bridges he would build in the county. Over the ensuing years he earned a reputation as the nations leading civil engineer, a discipline that was still in its infancy at the time. The breadth of his activities is staggering and included bridges, roads, canals and harbours. It is estimated that he built some 1,000 miles of new roads, including more than 1,000 bridges. He worked on over thirty canal projects, including the Caledonian Canal which sliced through Scotlands Great Glen from coast to coast. He worked on numerous harbour and dock projects, culminating with the construction of the St Katharine Docks in London. And built some of the most iconic major bridges and aqueducts to be found anywhere.

Detail of the ribs and spandrels on the Mythe Bridge, which crosses the River Severn to the north of Tewkesbury. Although Telford began his career as a stonemason, he willingly embraced the potential of iron as a building material for many of his bridges. (JC)

Unlike the famous men of iron of the Victorian era, Thomas Telford lived and died before the arrival of photography. This engraved plate shows the Waterloo Bridge at Betws-y-Coed in the background, which was built in 1815, making him around fifty-eight years old.

Telfords signature.

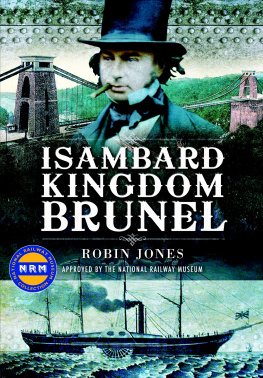

So why is it that Telfords achievements tend to be eclipsed by the next generation of engineers, the Victorian upstarts such as Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the Stephensons. Partly it is because of the nature of the projects he worked on. While canals have seen a massive resurgence in popularity among leisure boaters and tourists in recent years, they were already past their prime by the time of Telfords death. Added to which, their mostly rural location puts them out of sight for most people. His roads, on the other hand, are used by tens of thousands of people daily, but are taken for granted. In terms of public awareness the railways, which came to fruition so late in Telfords career and yes, he was involved with several railway schemes and took part in the survey of a proposed line between Glasgow and Berwick and even toured the route of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway with George Stephenson have remained an integral and highly visible part of everyday life in Britain. Telford remained loyal to the canals, believing that they and not the steam railways were the better means of transporting goods. He was also acutely aware of the antipathy felt by the railwaymen towards him as a canal builder. And, finally, there is the matter of his image; something that has become more significant with the passage of time and the increasingly visual way in which history is portrayed and perceived. For Thomas Telford had the misfortune to be born before the arrival of photography, especially photojournalism. Brunel, on the other hand, will be immortalised forever thanks in no small part to Robert Howletts iconic image of him posing in front of those gigantic chains prior to the launch of the Great Eastern steamship. It is, arguably, the most famous photograph of the nineteenth century. In contrast the only images we have of Telford are either formal paintings or engravings and prints. They lack the immediacy of the photograph and they dont seem to be especially accurate.

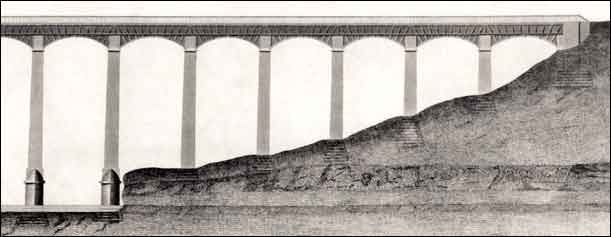

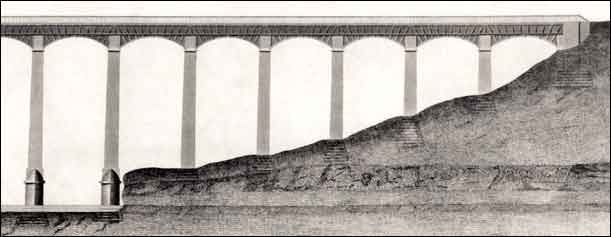

An engraving of the high Pontcysyllte aqueduct over the River Dee, from