MAN OF IRON

MAN OF IRON

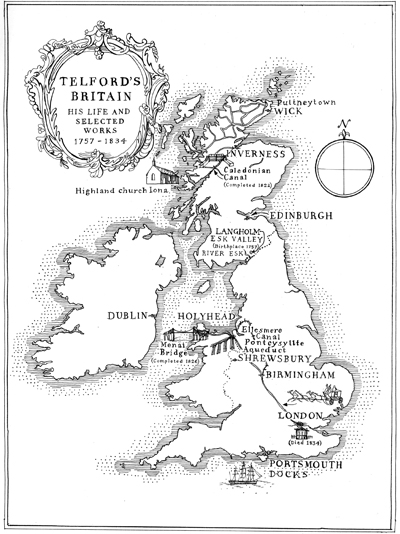

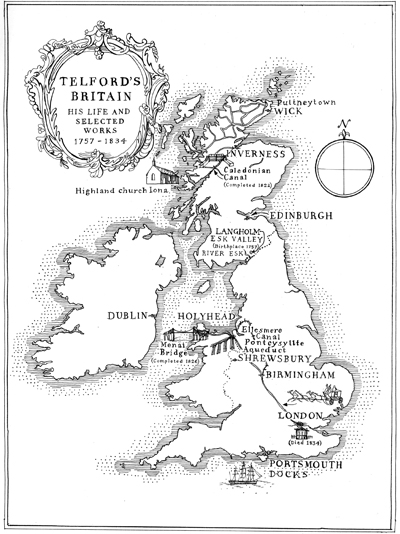

Thomas Telford and the Building of Britain

Julian Glover

Bloomsbury Publishing

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

www.bloomsbury.com

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain 2017

Julian Glover, 2017

Map artwork Emily Faccini

Julian Glover has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: HB: 978-1-4088-3746-7

EPUB: 978-1-4088-3747-4

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

To Matthew

CONTENTS

Menai in deep winter, well past midnight. To the east, the cold heights of Snowdonia; to the west, Anglesey and the Irish Sea. The wind was up, the tide was racing on the rocks below and rain was on its way. It was ordinarily no place for people without thick cloaks, tall boots and a pressing need to be out of their beds: but this night was different. There was a crowd, shouts, jostling, the stamping of hooves and the velvet smell of sweating horses. Bright lights reached down to the dark water that had separated Anglesey from the mainland for perhaps 4,000 years until this moment but would never do so again.

The modern world was arriving in North Wales that night in 1826. Everything was changing. And Thomas Telford was there. Thomas Telford was the man who made it happen. It was his new bridge people had come to see. His bridge they wanted to cross for the first time. And what they saw stretching into the darkness was indeed extraordinary: a structure as bold as anything built in Britain since the Romans, like a great blade cutting between water and sky. Technology was being tested to the limit that night. So was courage. No one could know for sure if the iron chains which held the bridge high above the Menai Strait would be safe; if Telfords design would be proved; if a mathematical dream would come true.

And now, from the road to the east, came the sound of hurry: iron-rimmed wheels and horses hooves galloping on rough gravel, racing to keep time. The Royal London and Holyhead coach was heading for the port: its scarlet sides and the royal crest proclaiming the right to carry the precious mailbag for Dublin. As it pulled up outside the Bangor Ferry Inn its exhausted horses were unharnessed and a fresh team attached. A man stepped forward with an air of command. He climbed quickly onto the top of the coach and sat down next to David Davies, the coachman on duty that night.

The mans name was William Provis and he had overseen the building of the Menai Bridge under Telfords instruction. Now, he broke his momentous news. This was to be the first coach to cross the new structure. Briefly, there was confusion: even an argument. Davies and his guard, William Read, resisted. Orders were orders, they said. They insisted they needed written instructions to change their route from the old Menai ferry. But Provis held firm. The bridge, he told them, was to open that night. That was final. He was taking command of the coach.

And now the excitement increased. A note was sent down to the ferryman on the Bangor shore to inform him that his boat was not needed that night. It would never be again. At about 1 a.m., with Provis by his side, the coachman flicked his reins, the horses strained and the coach set off on the short journey from the inn to the bridge. It was, one witness remembered, quite a sight, the high mounted steeds mantling their proud crescent necks, as if conscious of the triumphant achievement.

As the coach reached the bridge many more passengers tried to scramble aboard, wanting to be among the first to cross. The weather was wild. Amid glare of lamps (a heavy gale of wind blowing by this time), Provis recalled later, the passengers were joined by as many more as could be crammed in or find a place to hang by. Then, with the overloaded coach creaking, the iron gates that guarded the crossing were swung open for the first time. A crack of the whip put the horses in motion and we were quickly conveyed to the opposite end, amidst the cheers of the men around us and the shrill whistling of the gale.

And so, without more fanfare than this, on a horrible night at 1.35 a.m. on 30 January 1826, the Menai Bridge opened. It was the finest moment of Thomas Telfords career: at sixty-eight, he had built the most daring structure of his life, the first great suspension bridge of the modern age, its central deck almost 580 feet long, slung 100 feet above the tidal channel from sixteen thick chains. The bridge was this stupendous effort of human genius, one popular guide of the time declared. The Menai Bridge, he concluded, will rank, in future ages, as the Eighth Wonder of the World.

Telfords response to all this was telling. A different man would have sought public glory. A different man would surely have insisted on crossing first that night rather than letting his friends and juniors make the trip before him. A different man would have made a pompous speech or wanted to name the bridge after himself, or perhaps tried to call it after King George IV in the hope it would bring him rewards, just as a different man would have sought honours or riches throughout his life.

Telford wasnt like that, ever. If the design of his bridge exposes one side of his character relentless, daring, ingenious then the manner of its opening exposes another private, perhaps Soon after, the celebrated Oxonian stagecoach followed, heading for London and reputed to be the fastest in Britain. Then came a scrum of numerous Gentlemens carriages, landaus, gigs, cars, poney-sociables &c &c upwards of one hundred and thirty in number; and horsemen innumerable.

The Royal Standard flew from the great stone towers, cannons fired and competing bands played on either shore. Joy, admiration and astonishment seemed depicted in every countenance on beholding the proportion, symmetry and grandeur apparent to the most common observer, in every part of this unrivalled structure.

A party began. At one time the Bridge was so crowded that it was difficult to move along, Provis wrote in a letter the next day. Most of the carriages of the neighbouring gentry, stage coaches, post chaises, gigs and horses passed repeatedly over and kept up a continuous procession for several hours the demand for tickets was so great that they could not be found fast enough and many in the madness of their joy threw their tickets away that they might know the pleasure of paying again. Not a single accident or unpleasant occasion took place and everyone appeared satisfied with the safety of the Bridge and delighted that they could go home and say I crossed the first day it opened.

Next page