First published in 1999 by Aurum Press Ltd

Reprinted in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Transport

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Anthony Burton 2015

ISBN: 978 1 47384 371 4

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47386 408 5

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47386 407 8

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Ehrhardt by

Mac Style Ltd, Bridlington, East Yorkshire

Printed and bound by Imago

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, and Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

I n , the signed sketch of the unlikely design for an aqueduct is reproduced courtesy of the Science and Society Picture Library. All other drawings included within the text are reproduced courtesy of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

The maps in the gazetteer section are by Don Macpherson.

Preface

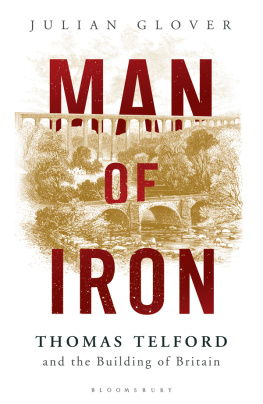

M y interest in Thomas Telford was first aroused around forty years ago when my wife and I set off, somewhat nervously, to steer across the mighty aqueduct of Pontcysyllte. At that time it was universally attributed to Telford, an attribution I was happy to repeat in my book The Canal Builders. Some years later I was approached by a publisher who asked if I would consider writing a new biography of Telford. I refused, on the not unreasonable grounds that everything that needed to be said about the man had already been said, and probably better than I could say it, by L. T. C. Rolt. I had, and have, the greatest admiration for Rolt, enhanced by the encouragement he gave to my work on The Canal Builders. The thought of competing was beyond contemplation.

It was another of the pioneers of transport history, Charles Hadfield, who began to put doubts in my mind. The publication in 1979 of the biography of William Jessop that he wrote with A. W. Skempton put a very strong case for rethinking the story of Pontcysyllte. Over the years Charles kept ringing up, rather gleefully, to say that he had found out something else about my man quite how Telford had become my man I was not sure. That process culminated in Charless last book, Thomas Telfords Temptation. It was now clear that re-evaluation was becoming necessary, and that perhaps the time had come to take up the challenge I had earlier rejected.

There has been an unhappy tendency among a minority of biographers in recent years to claim that their work is somehow better than that of their predecessors because they have been able to correct mistakes. What this usually amounts to is the discovery of previously unknown material that demands a rethinking of the story of the past. This happens all the time; if it did not, there would be little need for the new work at all. When I started work on this book, I was very conscious of just how much I owed to my predecessor. The very first thing I did was to reread Rolt, and enjoyed it as much as I had ever done. I was nervous, but not unhappy about starting. For one thing I felt very strongly was that if he were alive today, he too would be rethinking parts of the story and would have been getting the calls from Charles instead of me! The work of L. T. C. Rolt has been an inspiration to me throughout my professional career as an author, and I hope those who read this book will see it not as a replacement of his work but as a necessary continuation. My one sadness is that Charles is not here to argue about some of my opinions and argue he surely would have done. All I can do is to dedicate this book to the memory of two great pioneers of transport and engineering history, L. T. C. Rolt and Charles Hadfield.

Anthony Burton

Stroud, 1998

Preface to Second Edition

The book remains substantially the same as when it was first published: no one has contacted me to point out any embarrassing errors that were made first time round, nor has new research revealed any need to revise opinions. There have been minor changes affecting the illustrations, but not the main text. The one difference, from my point of view, is that since writing the original I have had the opportunity to travel the full length of the Gotha Canal. It was a delight to see this magnificent work and also to discover that parts still carry commercial traffic in the form of substantial cargo vessels. It was also encouraging to discover how greatly Telfords contribution was respected in Sweden. It reinforced my opinion that Telford ranks among the greatest engineers of all time, and I hope this new edition of the book will persuade others to share my opinion.

Anthony Burton

Stroud, 2015

Introduction

B iographies are often entitled The Life and Work of whoever the subject might be. In Telfords case it might be more appropriate to refer to The Work and Life of Thomas Telford, for that is surely the order in which he himself would have placed them. He worked continuously from the day he began as a boy, almost until the day he died, and it is by his works that he would want to be remembered. There is enough testimony by those who knew him to suggest that his was an affable character when he relaxed in company, but the truth is that relaxation was a luxury for which he had all too little time. One of the frustrations of writing this book at first was the lack of information about his private life. Grateful as one is to the likes of Robert Southey for his detailed account of accompanying Telford on the inspection of his engineering works, and for passing on what they looked like and what the engineer had to say about them, one cannot help wishing most fervently that he had told us what else they talked about. Similarly, Telford himself had very little time for letter writing, apart from official correspondence, but his private letters, mostly to the Little family, do at least give us a strong feel for his personality. Yet, while researching this book and hunting for information, it became steadily clearer how futile it was to try and separate the man from his work; engineering quite simply was his life, and there was little room left for anything else.

At first, I felt concerned that the engineering works were overwhelming the man, but as I went on, that worry began to disappear. More and more I realised just what a heroic life it was, how taxing both physically and intellectually. I became ever more impressed by the sheer range of challenges that Telford accepted and met. It is, I am aware, deeply unfashionable to consider the subject of engineering as anything other than terminally dull. In that case, I can only plead guilty to being hopelessly out of fashion. I have found in Telford a man who could not only solve problems, but could do so in wholly original ways. No plodding mentality could have done so; even to conceive of such structures as the Menai bridge required a huge act of imagination. To bring them to reality required a great deal more. So, to the reader looking for salacious gossip, I am sorry there is none. To those who hope to find Freudian analysis of a celibate who lost himself in work, I am afraid there is no such analysis. All that I have tried to do is to give a picture of what it meant to be one of the worlds greatest engineers at a time of the most profound changes. That seemed challenge enough for any biographer.