First published in Australia and New Zealand by Allen & Unwin in 2018

First published in the United States by Seven Stories Press in 2018

Copyright Klester Cavalcanti, 2006

Translation Nick Caistor, 2018

First published in Brazil as O Nome da Morte.

This edition was licensed by Seven Stories Press, Inc., the originating English language publisher, 2018.

Published by special arrangement with Villas-Boas & Moss Literary Agency & Consultancy and its duly appointed coagent, 2 Seas Literary Agency.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 232 8

eISBN 978 1 76063 610 4

Internal design by Jon Gilbert

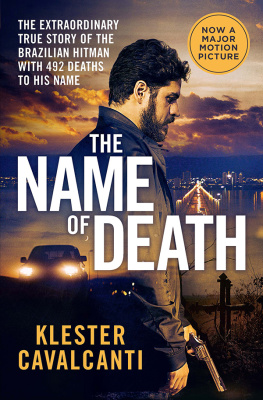

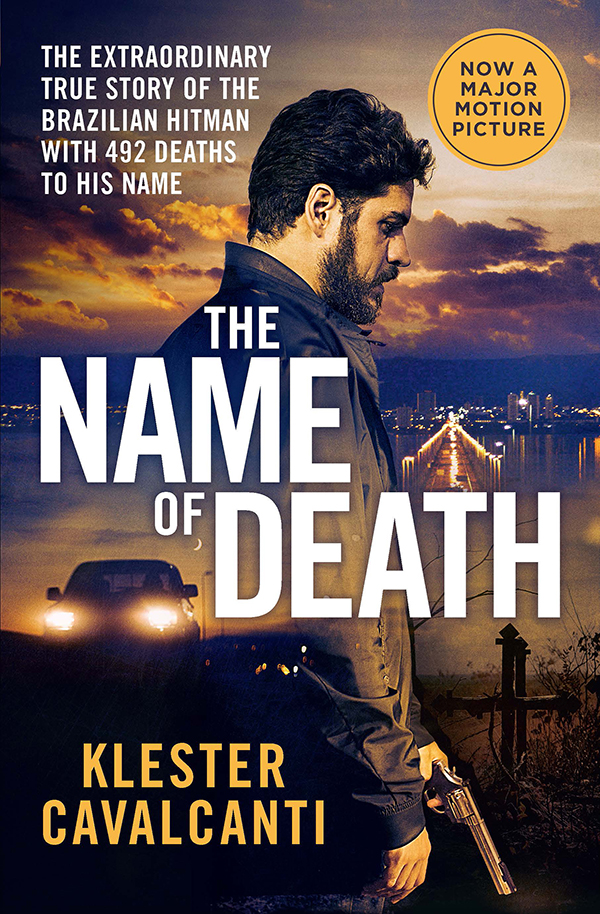

Cover design: Luke Causby/Blue Cork

Cover photo: Imagem Filmes

This book is dedicated to my parents, Dborah and Alcindo.

Also to my son, Diego.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To my brother, Kaike Nanne, for his ever-present love and support. To my friends Alexandre Mansur, Janduari Simes, Roberto Sadovski, and Valdemir Cunha, for their constant encouragement. To Isabel Malzoni, for her patience and dedication.

CONTENTS

IT TOOK SEVEN YEARS of interviews before Jlio Santana authorized me to put his real name in this book. The first time we spoke, in March 1999, he agreed to tell me his story, but did not want to reveal his identity or to allow meor anyone elseto photograph him. Thats easily understood. The man I started to interview from that day onat an average of once a monthis a professional killer who in thirty-five years of work has shot almost five hundred people. More precisely, 492 deaths, of which 487 were duly recorded in a notebook, with the date and place of the crime, how much he received for the job, and most important of all, the names of those who contracted him, as well as those of the victims.

My first contact with this intriguing Brazilian citizen came about while I was working on a report about slave labor. At that time, in March 1999, I was Veja magazines correspondent in Amazonia, a post I held for a little more than two years. For the report, the photographer Janduari Simes and I traveled to various towns in Par state, looking for people who had been enslaved and for ranchers who kept slaves on their properties. During an operation by the Federal Police and the Ministry of Justice in the town of Tom-Au, one of the policemen said it was common in the region for the ranchers to hire gunmen to kill relativesusually the children or brothersof slave workers who had fled their estates, as a way of forcing the slaves to return to work. Seeing my interest in talking to one of these killers, a policeman taking part in the operation told me he knew a gunman and would speak to him to see if he could give me his phone number. To anyone who knows how the Brazilian police operate, unfortunately this friendly relationship between criminals and the police is nothing new. But I only really believed this federal policeman was going to put me in touch with the killer two days later, when he contacted me to say he had already talked to the gunman and that I could phone him the next day, at precisely two oclock in the afternoon. The number he gave me was a public phone opposite a bakery in the town of Porto Franco, in Maranho state. On that Thursday, March 18, 1999, in a conversation that lasted almost half an hour, I learned that the name of the man whose story I wanted to tell was Jlio Santana, and that he had committed his first murder at the age of seventeen, in 1971.

From our conversation and his tone of voice, Jlio did not seem to me either violent or aggressive. He spoke in a calm, unhurried way, with a strong northeastern Brazilian accent. What was clear from our first contact was that he was keen to tell his story. If you like, Ill tell you everything, he said. Ive never told anyone these things. Before our conversation ended, we agreed to talk again five days later, at the same time. As soon as I hung up, I called the then executive editor of Veja in So Paulo, Laurentino Gomes, who had to approve my story ideas. He was enthusiastic about us doing the profile of a contract killer. But he said we could not publish such an outlandish, shocking story without at least giving the real name of the person involved. And if the killer agreed to pose for a photo, better still. Each time I talked to Jlio, I became increasingly fascinated by his story. But at the same time my hopes of him agreeing to us publishing his name and photo grew fainter and fainter. In the short term at least.

For the next seven years I continued my conversations with the man who killed close to five hundred people and never had any other profession. With every phone call our relationship became increasingly close. I felt as if he grew to trust me more and to tell his stories more sincerely and with greater emotion. Occasionally I would remind him of my wish to publish the story of his lifeby now with the idea of making it into a bookbut repeated that to do so it was absolutely necessary for him to authorize me to give his real name and a photograph. Jlio remained adamant. I was sure, though, that one day he would change his mind. This happened in January 2006. During one of our conversations, Jlio told me he had decided to abandon his life as a killer in order to live with his wife and two children in another state far away from Maranho.

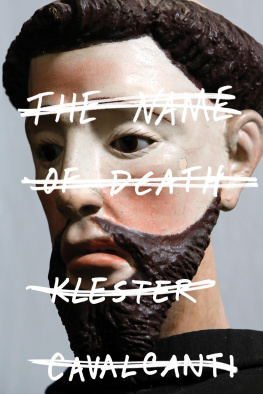

On hearing this, I managed to convince him that his greatest fearthat of being arrested if his name appeared in a bookno longer made any sense. Given that he was living in another state and leading a completely different life from the one he had led until now, the police would never find him. But if you put my photo in the book, theyll get me, Jlio said. I explained that the photo was indispensable but that we could doctor it so that his face would be unrecognizable. And as a proof of the extreme trust he had in me, he finally agreed to let me to put his name and photograph in the book. This book.

Yet something important was still missing: to meet the killer in person. Up until then, all my conversations with Jlio Santana had been by telephone. I had no idea what he looked like, how he walked, how he sat, how he smiled. I did not know the house he lived in, or his wife and children. In order to get to know him and his universe, in April 2006 I traveled to Porto Franco, where Jlio and his family lived. I spent three days there with a calm, good-humored, home-loving man who was affectionate toward his wife and children and very religious. A man apparently nothing out of the ordinary. A very different profile from that of the killers that abound in literature and the cinema.

WITH THREE NOTEBOOKS stuffed with notes exclusively from my conversations with Jlio, I turned to another aspect of my work: to find other sources, both documents and people, who would confirmor notthe stories told by the protagonist of this book. To do this I interviewed almost forty peoplefrom policemen to gold prospectors who worked at Serra Pelada, and including relatives of people killed by Jlio. I also had access to police investigations and judicial files. It was a relief to discover that these sources, both people and documents, convincingly confirmed everything Jlio had told me, as well as providing me with detailed information about the cases referred to in this book.