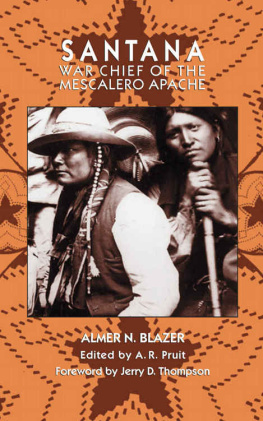

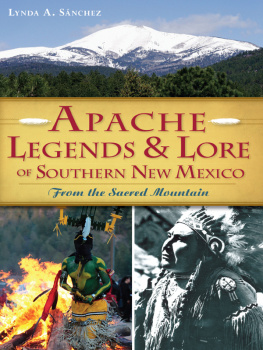

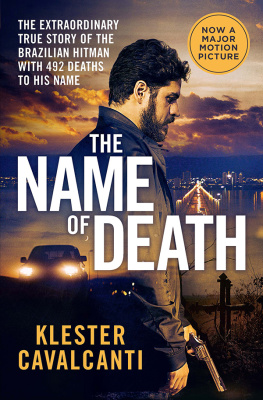

Drawn from previously unpublished firsthand accounts of the years 1862 to 1880, this book tells the story of a great chief who was targeted for death by the U.S. military as the worst of all the Apaches. After disappearing for eight years with his band, Santana emerged as war chief of all the Mescalero bands and eventually won the confidence of the U.S. Government. Using his gifts as a leader and negotiator, Santana was able to persuade the American authorities to prevent the surviving Mescalero Apache from being exterminated by the military. He was finally able to secure a reservation on their traditional homeland in the mountains of south-central New Mexico. Written in the 1940s, Almer N. Blazers historic manuscript is a vivid recreation of the day-to-day history of Santana and the beleaguered tribe who looked to his leadership during their gravest crisis. Blazer writes sympathetically of the tribes struggle for survival and gives accurate, authoritative descriptions of Mescalero life before it was forever changed by contact with European culture.

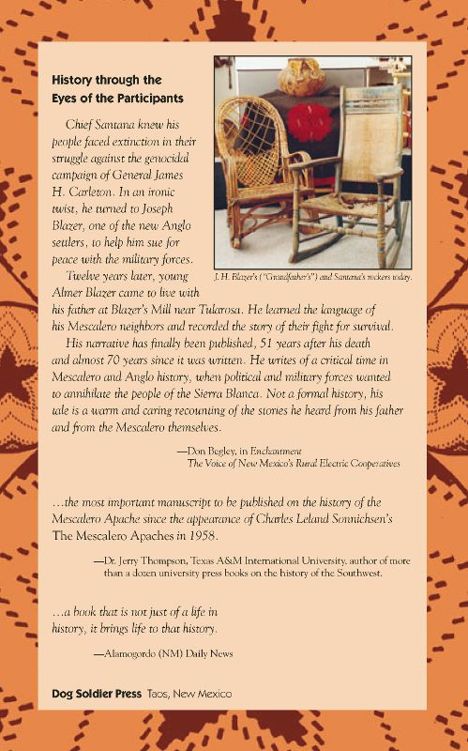

Almer Blazer grew up at his fathers mill, an isolated white outpost in Mescalero territory near Tularosa, New Mexico. The story of Santanas life and achievements comes from the detailed recollections of the authors father, Dr. Joseph H. Blazer, who was Santanas close personal friend and his firm ally in negotiations with the government. Growing up in close association with the Mescalero, Almer Blazer was present at rituals and participated in the typical activities of Mescalero boys. In his manuscript, Almer Blazer presented a vital picture of daily tribal life, customs, and religious beliefs. He faithfully transmitted what he saw, heard, and experienced, preserving oral history and cultural information that might otherwise have been lost during the Mescaleros brutal transition to modern life.

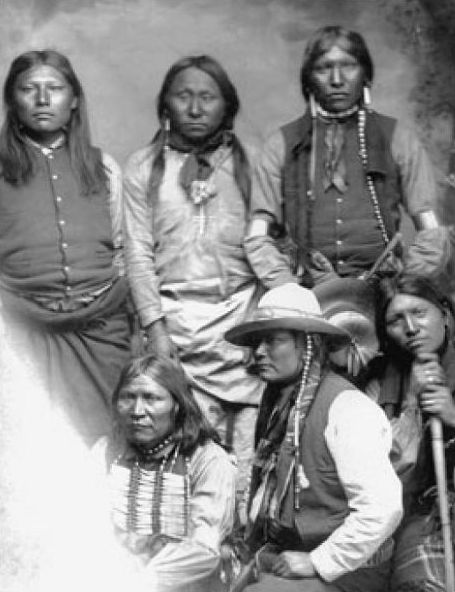

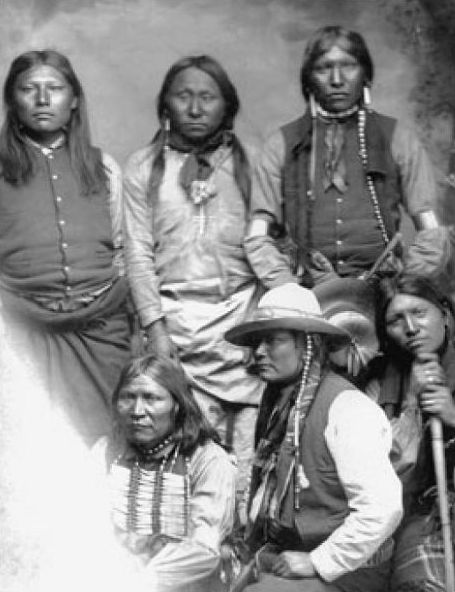

Dr. Pruits introduction reconstructs the historical events leading up to the time when Santana emerged as war chief. The book includes rare early photographs of the Mescalero Apache, many of which are from the Blazer family collection.

Dog Soldier Press

Taos, New Mexico

SANTANA

WAR CHIEF OF THE MESCALERO APACHE

To the Memory of

ALMER N. BLAZER

Some seed the birds devour,

And some the season mars,

But here and there will flower The solitary stars.

A. E. Housman

SANTANA

WAR CHIEF OF THE MESCALERO APACHE

Almer N. Blazer

Edited by A. R. Pruit

Foreword by Jerry D. Thompson

Dog Soldier Press

Taos, New Mexico

Copyright by Dog Soldier Press, 1999.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9718657-8-4

Kindle Edition

Dog Soldier Press

PO Box 1782, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico 87557

www.dogsoldierpress.com

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Photographs (cover and facing title page): Courtesy Rio Grande Historical

Collections, New Mexico State University Library; (back cover):Don Begley.

Contents

FOREWORD

B eneath the towering, snowcapped summit of Sierra Blanca in south-central New Mexico Territory in late 1867 or early 1868, two very different men met for the first time. One was Dr. Joseph Hoy Blazer, a big, blue-eyed, solidly built Iowa Civil War veteran, who never saw an Indian until he was forty years old. The other man was also tall, with a broad, calm face and great dignity of manner. He was Mescalero War Chief Santana. In the years that followed, the two men formed a unique and trusting friendship. In the words of C. L. Sonnichsen, Blazer was one of the very few white men whom the Mescalero trusted and accepted. Blazer had purchased a sawmill, La Maquina, in the Sacramento Mountains in the heart of the Mescalero country; in time, it became known as Blazers Mill.

Often preyed on by crooked traders, harassed by land-hungry settlers, starved, lied to, and attacked by the army, Santana and the Mescalero found Blazer to be a striking contrast to other white men they had known. Blazer was to learn much from Santana, who had been a leader of considerable influence among the Mescalero since at least 1830. Long at war with the Mexicans, the Mescalero had watched in 1850 as a new invader penetrated the traditional homeland of the White Mountain Apache. A detachment of bluecoats out of the Rio Grande Valley crossed the Organ Mountains, the arid Tularoso Basin, and rode into the rugged, pine- and fir-crested mountains to the east. With perhaps as many as three hundred warriors, Santana, by sheer intimidation, drove off the invaders. Yet shortly thereafter, Santana, along with the Jicarilla Apache and Comanche, proposed peace to the governor of New Mexico. When peace failed, the chief exerted every effort to keep his band, which never numbered more than a few hundred, as isolated and far away from the white man as possible. Yet again in January 1855 Santana was at the head of the Mescalero band that confronted the army on the Peasco River and killed Captain Henry Whiting Stanton.

After the death of chiefs Barranquito in 1857 and Manuelito in 1862, Santana continued to rise in the Mescalero hierarchy. During the relentless and genocidal 18621863 campaign against the Mescalero by General James H. Carleton, Santana managed, probably by secluding himself and his followers in the rugged canyons of the Sacramento and Guadalupe mountains, to avoid capture and the humiliation of confinement at the Bosque Redondo Reservation.

During the following decade, through clever negotiations and with the mediation of Joseph H. Blazer and other whites who supported the Mescalero, Santana was able to secure a reservation that preserved a substantial remnant of his peoples homeland. In the great smallpox epidemic of 1876 that swept the area, Santana, an old man by this time, was seriously afflicted and was taken in and nursed by Joseph H. Blazer at The Mill. Shortly thereafter, the chief returned to his lodge only to die of pneumonia. Joseph H. Blazer died in 1898.

Almer Newton Blazer, son of the doctor, first came to the reservation as a boy of twelve in 1877a year after Santanas death. The younger Blazer also became a trusted friend of the Mescalero as well as an authority on the White Mountain Apache. Educated at Las Cruces and Santa Fe, he was anxious that Mescalero history be preserved and wrote articles on the Apache and the history of the area.

Over the years, the Blazer familys knowledge and records have proven indispensable for any study of the Mescalero. Any serious scholarship on the subject necessitates the use of these records. J. Evetts Haley, Eve Ball, William A. Keleher, A. M. Gibson, C. L. Sonnichsen, and Robert M. Utley as well as other scholars, have all used the Blazer records and information obtained from the family.

When Almer N. Blazer died in 1949, he left behind a valuable and informative book-length manuscript entitled Santana: War Chief of the Mescalero. In the manuscript, Blazer repeated much of what he had learned from his father as well as older Mescalero who had known Santana. A. R. Pruit, who grew up with the Blazer family and who has had a lifetime interest in the Mescalero, has at last brought the manuscript to publication. Through meticulous research of historical archives, Pruit verified much of what was in the manuscript and uncovered a considerable amount of data pertinent to the war chief and Mescalero history, even for the years (18551872) when Santana was thought by white men to be dead. Much of this information has not previously been seen by scholars.

Next page