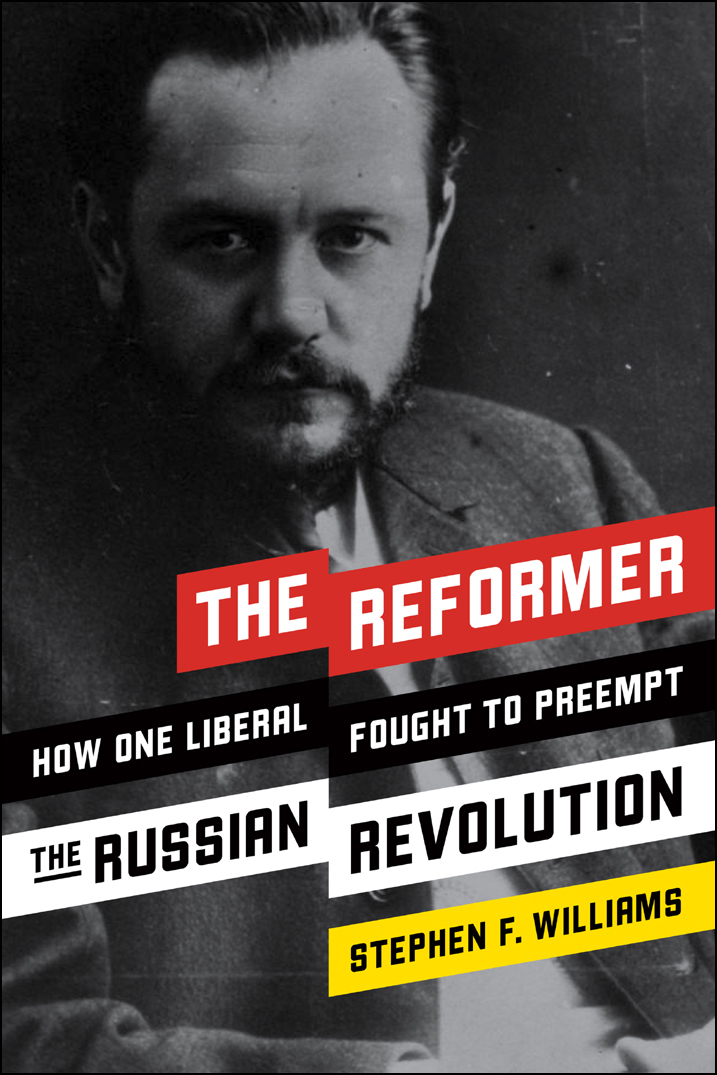

Vasily Maklakov in St. Petersburg. State Historical Museum, Moscow.

2017 by Stephen F. Williams

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of Encounter Books, 900 Broadway, Suite 601, New York, New York 10003.

First American edition published in 2017 by Encounter Books, an activity of Encounter for Culture and Education, Inc., a nonprofit, tax-exempt corporation.

Encounter Books website address: www.encounterbooks.com

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

FIRST AMERICAN EDITION

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Williams, Stephen F., author.

Title: The reformer: how one liberal fought to preempt the Russian Revolution / by Stephen F. Williams.

Other titles: How one liberal fought to preempt the Russian Revolution

Description: New York: Encounter Books, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017006458 (print) | LCCN 2017035181 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594039546 (Ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Maklakov, V. A. (Vasilii Alekseevich), 18701957. | PoliticiansRussiaBiography. | ReformersRussiaBiography. | LiberalismRussiaHistory20th century. | RussiaPolitics and government18941917.

Classification: LCC DK254.M23 (ebook) | LCC DK254.M23 W55 2017 (print) | DDC 947.08/3092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017006458

PRODUCED BY WILSTED & TAYLOR PUBLISHING SERVICES

Design and composition: Nancy Koerner

is an extension of this copyright page.

Dick Williams

and

Jack Powelson

Who kept asking useful questions

They also proposed quite a few answers

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

I want to thank some of the many people whose kindness, scholarly prowess, and general helpfulness made this book possible, recognizing that Ill likely forget to name some key contributors. First, Im deeply indebted to Lars Lih, Daniel Orlovsky, and Melissa Stockdale, who provided in-depth criticism and suggestions in their peer reviews and who engaged with me long thereafter. Many other scholars of Russian history also extended a welcome to this visitor from the world of law, ready to answer questions, point me to resources, chat about related (or unrelated) issues of Russian history, and offer useful suggestions. Among the many providing expert help (including partial readings) were Abe Ascher, Ira Lindsay, Jonathan Daly, Robert Weinberg, Albina and the late Igor Birman, Alex Potapov, Ilya Beylin, and Olga Zverovich, and Peter Roudik and Ken Nyirady of the Library of Congress. I am in debt to Abe for far more than his reactions to particular segmentshis astute observations, encouragement, friendship, and laughter date back to nearly twenty years ago, when I first thought of doing real work in Russian history.

Im also indebted to Peter Reuter, Peter Szanton, and Matt Christiansen for readings of the whole book, and Peter Conti-Brown and David Tatel for partial readings, all from the perspective of intelligent, well-informed citizens. David Dorsen, Mike OMalley, Amanda Mecke, Max Singer, Emmanuel Villeroy, and Jonathan Zittrain have provided all kinds of clues and ideas, as well as valued hand-holding and consultation.

Many thanks to Zhanna Buzova for hours spent untying the linguistic knots in Maklakovian sentences that first eluded me. I am grateful to the good people at Wilsted and Taylor Publishing Services for close copy editing and massaging the book to readiness for publication, and to Katherine Wong at Encounter Books for attentive support over the past year. Finally, thanks to all members of my family, especially to my wife, Faith, for readings, comments, and a well-calibrated mix of nudges and cheerleading.

The only way to avert a revolution is to make one.

ANTOINE PIERRE BERRYER

I N OCTOBER 1905 Tsar Nicholas II issued the October Manifesto, opening the door for the first time in Russias history to real-world political advocacyadvocacy that could affect the election of legislators, who in turn could pass laws controlling government action. This book is an account of the efforts of Vasily Maklakov, a lawyer, legislator, and public intellectual who used this opportunity to advance the rule of law in Russia. Though his efforts were clearly not enough to prevent the Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917, they illuminate the kind of challenge that reformers face today in authoritarian regimes around the globe.

In the October Manifesto the tsar promised to allow freedom of conscience, speech, and assembly and to establish an elected legislature. He also took a pledge to the rule of law. Under the manifesto, a law could take effect only with the consent of the legislature, rather than merely by decree of the autocrat, as before. And compliance with law would be an essential condition for valid executive action. If fully implemented, the manifesto would have created a government of laws.

As a trial lawyer, Maklakov regularly observed the practical qualities and defects of the rule of law in early twentieth-century Russia. He was renowned for being able to sway juries and judges with calm conversational logic. As a legislator he used his analytic and forensic skills to press for reform of Russia and reduce the risk of revolution, advocating, for example, a practical integration of peasants into Russian society and an end to religious and ethnic discrimination. He wrote for newspapers and intellectual journals on vital issues of the day. He appeared to move with ease between technical legal issues and the more philosophical questions of how law might enable the creation of a free society. His arguments delineate a Russia that might have beena Russia struggling with corners of backwardness, to be sure, but liberal, open, welcoming previously unheard voices, and developing institutions that could channel conflict into lawful paths.

As participant and observer, actor and critic, Maklakov is an inviting lens through which to view the last years of tsarism. Born in May 1869, he received a degree in history before getting one in law. He was on the political stage from shortly before the October Manifesto until the Bolsheviks took power in 1917. Named ambassador to France by the Russian Provisional Government, he set off for Paris on October 12, but was unable to present his credentials before the provisional government fell. Although active thereafter as the effective dean of the Russian migr community in France, he was also able to write the story of the revolution and its background in several books of lucid and engaging prose. Like any historian-participant, he occasionally spun events to fit his views at the time of writing, but through his contemporaneous speeches and writings we can detect cases where he adjusted historyusually only slightlyto reflect a new outlook. And his charm and capacity for friendship with people radically different from himselfLeo Tolstoy and the maverick Social Democrat Alexandra Kollontai come quickly to mindcreated a trail of relationships far beyond the ken of most lawyer-politicians, however distinguished.