Copyright 2019 by Ruth Kassinger

Illustrations 2019 by Shanthi Chandrasekar

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kassinger, Ruth, author.

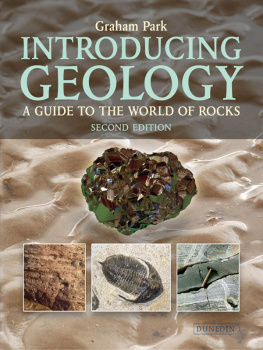

Title: Slime : how algae created us, plague us, and just might save us / Ruth Kassinger.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018043835 (print) | LCCN 2018044781 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544433151 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544432932 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Algae.

Classification: LCC QK566 (ebook) | LCC QK566 .K37 2019 (print) | DDC 579.8dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018043835

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

Cover image Getty Images

Author photograph Stone Photography

eISBN 978-0-544-43315-1

v1.0519

For Ted

Introduction

Algae. When you read the word, what pops into your mind? A bright green ring of slime around an outdoor drain? Dark green fuzz obscuring the glass of a fish tank? Pea-soup scum blanketing a pond in midsummer?

Whatever unpleasant image it is, I understand. Before I wrote this book, if Id heard algae, Id have instantly recalled the greenish hems on the damp shower curtains in the girls locker room at Pimlico Junior High. Seaweedsthese are algae, toowould have triggered another unpleasant memory. As a child, I learned to swim in a lake at summer camp, starting in the Guppies class and moving up to Minnows. The Minnows practiced a dozen yards from the shore, where the water was chest-high. Seaweeds grew in patches out there on the silty bottom, but I kept my eyes open underwater and usually managed to steer clear. Sometimes, though, if an earlier class had churned the shallows and clouded the water, I would accidentally blunder into them. Their caresses along my bare arms and legs would send me into a panicthe slippery vines seemed as if they might wrap around me and pull me under. Id bolt to my feet, gasping, and flounder my way out.

After the age of eight (when I graduated to Sunfish and swam beyond the dock in deeper water), I rarely thought about algae. And then, quite suddenly, in December of 2008, I began to think about them a lot. That was when, in researching another book, I visited Valcent Products, a startup biofuel company operating in a greenhouse in the dusty outskirts of El Paso, Texas. Founder Glen Kertz, backed by millions of dollars in venture capital, was growing algae in dozens of vertical, clear plastic panels, each ten feet tall by four feet wide and a few inches thick. Inside the panels, a water-and-algae mixture flowed through serpentine channels. That day, with sunlight streaming down from overhead, the panels glowed a bright, almost otherworldly green. Kertz, a man built on the Daddy Warbucks model with candid blue eyes, explained that the color would deepen almost to black as the algae within doubled and redoubled. Once a day, half the contents of the panels was siphoned off and sent into a powerful centrifuge that separated the algae from the water, leaving an algal paste. The paste was then heated under high pressure to extract the oils inside, oils that wouldwhen Valcent perfected its operationsbe sold to a refinery to be processed into gasoline, diesel, or jet fuel. New water was added to the panels every day, so algae were perpetually on the job.

Success, Kertz asserted, was just around the corner; Valcent would soon be producing one hundred thousand gallons of fuel per acre. Like the many journalists writing awestruck articles about the company, I was ready to be convinced. After all, crude oil is made of ancient algae, compressed over millions of years below ground. Valcent would be doing in a short time what Earth has been doing, slowly, for ages. By burning algae fuel in our vehicles, we would be taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere rather than putting long-sequestered carbon into the atmosphere, as we do when we burn fossil fuel. Because 14 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions comes from burning transportation fuel, switching to algae oil would have a significant impact on climate change. Bonus points: growing algae requires no arable land and no fresh water, both valuable and increasingly scarce resources on our planet.

Unfortunately for his investors, Kertz wasnt much of a scientist or engineer, and shortly after my visit, Valcent went out of the oil business. (So much for those candid eyes.) Although Kertzs oil-per-acre figure was too high by a factor of at least ten, the science behind algae fuel is perfectly correct, and a host of other companies, mostly small startups but also Exxon, had begun developing the multiple technologies involved. I eagerly followed the progress of these entrepreneurs, trying to figure out what was really possible. As I did, I found myself increasingly engagedand ultimately engrossedby the little green cells at the heart of these enterprises. Biofuels, as it turns out, are only a small part of the promise of algae.

My fascination became this book. It is the story of my journeyby phone, plane, car, boat, drone, and scuba fins, across the US and around the globe from Canada to Wales to South Koreato understand how algae, the most powerful organisms on the planet, influence our lives, for better and for worse, and what role they will play in our future. I start deep in Earths history and travel to the bleeding edge of modern biotechnology. Along the way, I meet scientists and entrepreneurs who have been harnessing these tiny dynamos to improve our health, nourish our ever-growing human population, and clean up the mess we are making of our planet.

Algae are Earths authentic alchemists. Using sunlight for power, they take the dross of carbon dioxide and, with water and a scintilla of minerals, turn it into organic matter, the stuff of life. Even better, as they work their combinatorial magic, they burp oxygen. Take a breath: At least 50 percent of the oxygen you inhale is made by algae. What is waste to them is priceless to all respiring animals. Without algae, we would gasp for air.

There is no shortage of algae. The oceans are blanketed in a dense but invisible six-hundred-foot-thick layer of them. There are more algae in the oceans than there are stars in all the galaxies in the universe. Swallow a single drop of seawater, and you could easily down several thousand of these unseen beings. They are the essential food of the microscopic grazing animals at the bottom of the marine food chain. If all algae died tomorrow, then all familiar aquatic lifefrom tiny krill to whaleswould quickly starve.

In fact, if algae hadnt evolved more than 3 billion years ago and oxygenated the atmosphere, multicellular creatures would never have graced the oceans. It was a species of green algae that, 500 million years ago, acclimated to life on land and evolved into all of Earths plants. Without plants to eat, the first marine animals that wriggled out of the water 360 million years ago would never have survived or continued to evolve and diversify into all the land-living creatures we know today, including us. If, several million years ago, our ancestor hominins hadnt had access to fish and other algae-eating aquatic lifeand thus to certain key nutrientswe would never have evolved our outsize brains. Without algae, we couldnt know that all of life depends on algae.

Algaes influence extends long after their death. Their microscopic, carbonaceous corpsesthose that dont become food for aquatic animals and bacteriadrift down through the ocean like a steady snowfall. On the ocean floor, they silently accumulate, their carbon remains sequestered for eons. By transferring carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to long-term storage, algae help keep our planet from becoming an unbearable hothouse. About fifty million years ago, when the Arctic was last ice-free year-round, a million-year burst of algae growth cooled the atmosphere to help create the icy conditions we see today.