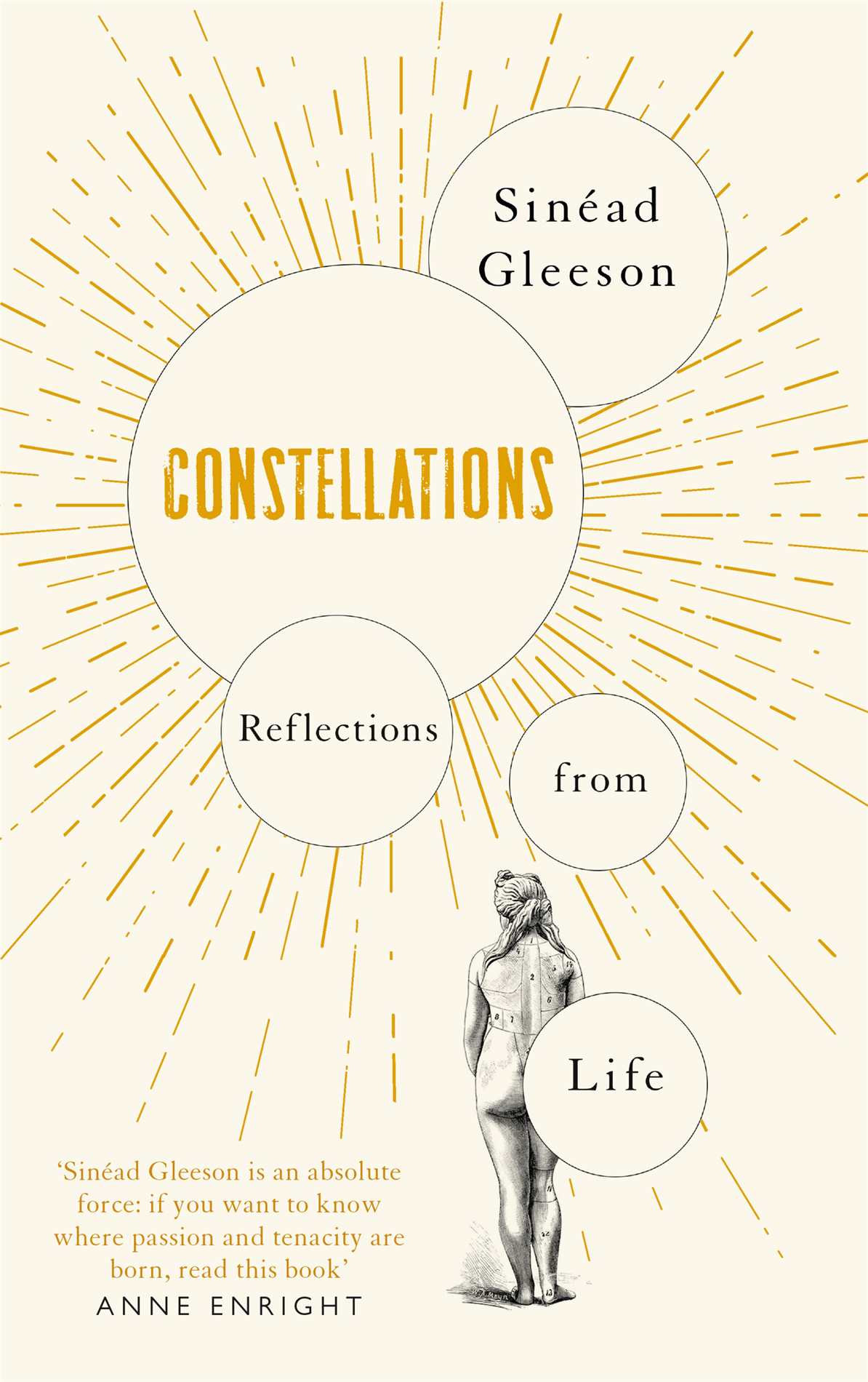

Sinéad Gleeson - Constellations: Reflections from Life

Here you can read online Sinéad Gleeson - Constellations: Reflections from Life full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Pan Macmillan UK, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Constellations: Reflections from Life

- Author:

- Publisher:Pan Macmillan UK

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Constellations: Reflections from Life: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Constellations: Reflections from Life" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Constellations: Reflections from Life — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Constellations: Reflections from Life" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To Steve,

For everything.

And in memory of Terry Gleeson.

Reflections from life

Sinad Gleeson is a writer of essays, criticism and fiction. Her writing has appeared in Granta, Winter Papers and Gorse, and a story of hers appears in Being Various: New Irish Short Stories published by Faber in May 2018. She is the editor of three shortstory anthologies, including The Long Gaze Back: an Anthology of Irish Women Writers and The Glass Shore: Short Stories by Women Writers from the North of Ireland, both of which won Best Irish Published Book at the Irish Book Awards. Sinad has worked as an arts critic and broadcaster and has presented The Book Show on RT Radio 1. She lives in Dublin.

Censor the body and you censor breath and speech at the same time. Write yourself. Your body must be heard.

Hlne Cixous, The Laugh of the Medusa

Empirically speaking, we are made of star stuff. Why arent we talking more about that?

Maggie Nelson, The Argonauts

I stood beneath the flag of motherhood and opened my mouth although I did not know the anthem

Liz Berry, The Republic of Motherhood

Maybe the body is the only question an answer cant extinguish.

Ocean Vuong, from Immigrant Haibun, Night Sky with Exit Wounds

The Bullet Catch

The body is an afterthought. We dont stop to think of how the heart beats its steady rhythm; or watch our metatarsals fan out with every step. Unless its involved in pleasure or pain, we pay this moving mass of vessel, blood and bone no mind. The lungs inflate, muscles contract, and there is no reason to assume they wont keep on doing so. Until one day, something changes: a corporeal blip. The body its presence, its weight is both an unignorable entity and routinely taken for granted. I started paying particular attention to mine in the months after turning thirteen. When a pain, persistent and new, began to slow me down. My body was sending panicked signals, but I could not figure out what they meant. The synovial fluid in my left hip began to evaporate like rain. The bones ground together, literally turning to dust. It happened quickly, an inverse magicians trick: now you dont see it, now you do. From basketball and sprinting to bone sore with a limp. Hospital stays became frequent, and I missed the first three months of school four years in a row.

Doctors tried everything to solve the mystery: firstly, by applying slings and springs a jauntily named type of traction that sounded to me like a clown duo. Then surgery. Biopsies. An aspiration: a name that suggests hopefulness, but yielded no results. My godmother Terry visited daily, bringing dinners and soft toys shed won in claw-crane machines, while my bones continued to disintegrate.

The eventual diagnosis was monoarticular arthritis. Doctors mentioned an operation called an arthrodesis, which, even in the late 1980s, they were reluctant to perform. Especially on girls, the surgeon told my parents amid much throat clearing, but I didnt discover what he meant until years later. That I would have years of wishing my body could do things it couldnt do, and explaining myself to others.

Numbers and Rituals

In the Bible, there is a story in Genesis of Jacob wrestling with a stranger, thought to be an angel. When the angel couldnt defeat him, he touched Jacobs hip, dislocating it, leaving him with a limp for life. Jacob was circumspect, viewing it as a reminder of his mortality, of the fact that the angel spared his life. That the spiritual self is more powerful than the physical body.

I was a pious child. Weekly Mass, regular trips to confession, and above all a fervent and deeply held belief in God, heaven and all the saints. This was reinforced by heavy indoctrination at school. In the local church, I bought books of religious poetry from a friend of my grandmother, who had a stall near the confession box. The poems were stanzas about nature; predictable rhymes steeped in Pantheism. The covers were always of fields, skies and flowers. Real majesty of the Lord stuff but I coveted these books with their small folio and cheap binding.

In the late 1980s, Irelands Catholicism had not yet unravelled. Priests still inspired fear in their congregations, but it was long before it was discovered that some of them had been raping children. A very specific kind of mistreatment was meted out to women. Contraception had been illegal until 1979, and then available on prescription. Being difficult to obtain made crisis pregnancies common. Until the 1960s, a married woman might be permanently pregnant: eight, ten, twelve pregnancies were not unusual. I hear it as one word eighttentwelve as though the numbers dont matter. As though double-figure pregnancies were to be stoically endured, like flu or a headache. Friends of my mother went to England and brought back suitcases full of condoms to pass around like war rations.

When my older brother was born in 1970, my mother had to be churched before she was allowed to return to Mass. The priest blessed all new mothers, cleansing them of impurity for having had a baby. In the eyes of holy men, even giving birth tainted womens bodies. It was not until 2018 that Ireland held a referendum on abortion, and passed a limited law for terminations in certain cases of up to twelve weeks.

Rope Lanes

The first hospital stay is three weeks long, followed by various types of physiotherapy: outpatient appointments and mandatory daily swimming. For three months in winter my mother drove me to a pool daily. We both got bored of the cold, and the same blueness; of me swimming lengths of front crawl and breaststroke over mosaic tiles. Days became weeks, and I propelled myself through lanes of lukewarm chlorine without incident. Until one night a group of rowdy teenage boys slammed into me, a foot knifing into my hip. The unexpected pain had the effect of a power cut. My body stopped, my brain tried to figure out what had happened. No flailing, just stillness. I stared into the chlorine blur and wondered if the joint was damaged, sinking until a lifeguard dove in and fished me out.

My grandmother used to work at another local pool, and convinced her old colleagues to let me swim there when it was closed. Alone, with the underwater lights, its tiled bowl felt eerie. All that blue, and quiet, the water shadows on the ceiling. I scared myself by imagining what lay beneath. Each week, I swam faster and got stronger. My body became an inverse: strong arms, while the weak left leg refused to move or build muscle. It withered, and is still thinner than the right. My lack of symmetry endures.

1988

In 1988, Dublin is a thousand years old, and the city celebrates with parades and commemorative milk bottles. The focus-grouped slogan for the year is Dublins Great in 88.

In 1988, I am thirteen, and Ray Houghton scores for Ireland against England in the European Football Championship. Headscarfed women like my grandmother light candles in churches in the hope well beat the Soviet Union (we draw) and the Netherlands (we lose).

In 1988, my mother brings me to an old redbrick house near Dublins South Circular Road. The woman who lives there owns a small glass relic of Padre Pio, containing some of his bone. My hip and the bones of a Catholic saint are briefly united as she rubs it over my hip with a susurration of prayers. Although nothing happens in the weeks that follow, my faith stays strong. I develop a habit of dipping my fingers in the holy water font at Mass and flicking a few drops in the general direction of my pelvis.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Constellations: Reflections from Life»

Look at similar books to Constellations: Reflections from Life. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Constellations: Reflections from Life and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.