FIRST PUBLISHED IN PRINT FORMAT 2015 BY

The Collins Press

West Link Park

Doughcloyne

Wilton

Cork

Kieran Fagan 2015

Illustrations Fiona Aryan 2015

Kieran Fagan has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Irish Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000.

All rights reserved.

The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for permissions should be addressed to the publisher.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-84889-246-0

PDF eBook ISBN: 978-1-84889-907-0

EPUB eBook ISBN: 978-1-84889-908-7

mobi ISBN: 978-1-84889-909-4

Typesetting of print edition by

Carrigboy Typesetting Services

Cover design by Fairways Design

KIERAN FAGANS interest in miscarriages of justice was prompted by living close to 10 Rillington Place in London in the 1960s. At that address serial killer John Christie had lived, and also Timothy Evans, who was hanged for murders later shown to be the work of Christie. The author is a retired journalist who has worked for The Irish Times, Irish Independent and Sunday Tribune.

For Alana, Anahita and Afshn

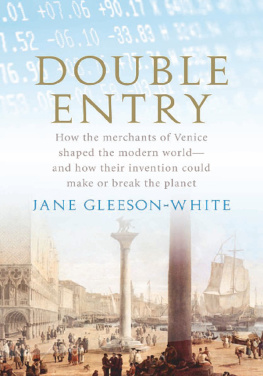

Harry Gleeson with some greyhounds, which were his great passion. COURTESY TOM GLEESON

W hen I first began to look into this subject, in late 2009, I thought the job involved finding out the names of those who had murdered Mary McCarthy, or Moll Carthy as she was known locally. My plan was to bring the story up to date by publishing the names of those responsible, thus exonerating Harry Gleeson, the man hanged in April 1941 for Moll McCarthys murder. Not long after I had begun, however, I was sidetracked by another project, and when I returned to Molls murder in late 2011, I found that my purpose had shifted: I was less focused on who had killed her. After all, an earlier writer on the subject, Marcus Bourke, though he stopped short of naming the guilty parties, had left plenty of clues pointing to their identity. The key for me became to ask other questions. Why did they do it? How did they get away with it? This book, I hope, explains how a series of overlapping events and interests caused an innocent man to be hanged.

In looking into these matters, I found that I had to ask some hard questions of those still living, and prompt the living to ask even harder questions of the dead.

Look at the bare facts: a woman was murdered and a man was hanged for her murder. Yet most of their neighbours and friends knew at the time that the evidence that pointed to Harry Gleeson being the murderer was sketchy. Others knew, or thought they knew, that he had not killed anyone. So why did so few speak up for him? And if not then, why not later? Why, in the early 1990s, when first Bill OConnor and then Marcus Bourke had published books showing grave flaws in the murder investigation and the trial of Harry Gleeson, did people not speak out and demand that his reputation be restored?

There was, and still is, a conspiracy of silence. Molls promiscuous relations with certain men in New Inn, County Tipperary, and beyond left many families with guilty secrets. Fear was another factor. If Harry Gleeson did not commit the murder, then those who did were still living in the community and had shown that they were not to be trifled with. So this conspiracy of silence could more accurately be described as a reign of terror, as Sen Delaney of the Justice for Harry Gleeson campaign group pointed out to me. However, even after all the protagonists had died, there remained little appetite for confronting the truth. All this contributed to unease in a community that knew it had looked the other way when trouble had come to a neighbours door. There were then, as there are now, honourable exceptions, and it is to them we owe the truth.

The townland of Marlhill, close to the village of New Inn, came to the attention of the wider world following the events of Thursday, 21 November 1940, when a farm manager, out checking on sheep, found the body of a woman with gunshot wounds. That single event would enmesh the lives of ordinary people and international figures, lawyers, diplomats and international peacemakers, film-makers and novelists, and its consequences continue to engage the attention of the public to this day. This book is an attempt to disentangle the threads that came together in what was a fairly typical community in the Irish countryside, not long after the Second World War had begun. However, there are some questions to which we will never find answers.

Where people are quoted, the text is taken from the official record unless otherwise indicated. There are conflicts in evidence between old time and new time because some rural people did not change their clocks for daylight-saving time. These conflicts can get in the way of comprehension. Previous writers tried to adjust the text to adopt one. I have chosen not to alter the record, but to ensure that, where timing is critical to understanding what is going on, the time lapse between events is given correctly.

T he village of New Inn is a pleasant, quiet backwater today, less busy than it was some seventy-five years ago. Then, it was on the main Dublin-to-Cork road, about halfway between Cashel and Cahir, and had a busy garda station with a complement of four men. The girls secondary school was a hive of activity, just across the road from a modest parish church and quiet graveyard. Vincent OBrien had not yet begun training horses at nearby Ballydoyle, but the land was good, and many farmers prospered in the Golden Vale, some of the finest agricultural land in Western Europe. Because of wartime supply shortages, farmers were required to plant crops, although much of the land was better suited to grazing high-quality livestock, as generally happens today.

The motte (or moat, in local parlance) of Knockgraffon is an imposing man-made earthen mound, an Anglo-Norman settlement, from the twelfth or thirteenth century, which survives to this day. Nearby is Rockwell College, in the 1940s a day and boarding school for boys run by the Holy Ghost order, now co-educational, where a young amon de Valera taught briefly. Knockgraffon National School, scene of some of the events in this book, closed its doors for the last time in 1992, though it outlasted New Inn Secondary School by ten years.

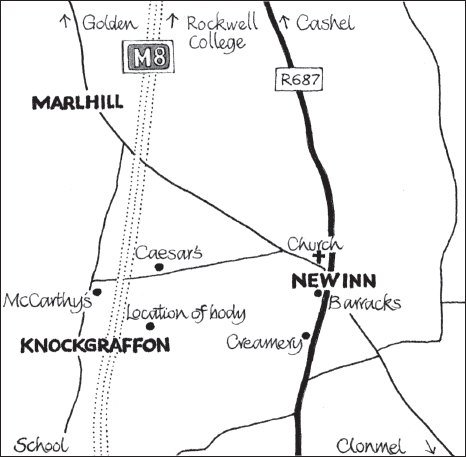

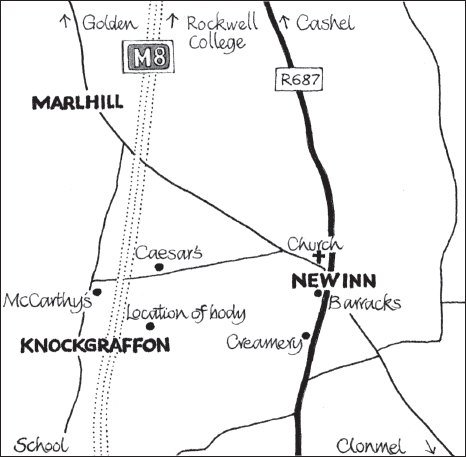

Map of the MarlhillKnockgraffonNew Inn area today, showing M8.

COURTESY FIONA ARYAN

But a resident of New Inn from 1940 would not recognise much else about the landscape. In recent years, the M8 motorway has severed the area. The very contours of the land have changed because the motorway passes through on a raised embankment. Farmers lost many acres when the motorway was built. John Caesars farm in the townland of Marlhill where Mary McCarthys body was found in November 1940 was bisected, and what remains of it now lies on either side of the motorway, with access via a tunnel.

Next page