17OO

Scenes from London Life

MAUREEN WALLER

Hodder & Stoughton

Copyright 2000 by Maureen Waller

First published in Great Britain in 2000 by Hodder and Stoughton

A division of Hodder Headline

The right of Maureen Waller to be identified as the Author of the Work

has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 0 340 73966 5

Hodder and Stoughton

A division of Hodder Headline

338Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

For my parents,

Margaret Mary and John Gamble Waller,

with love and gratitude

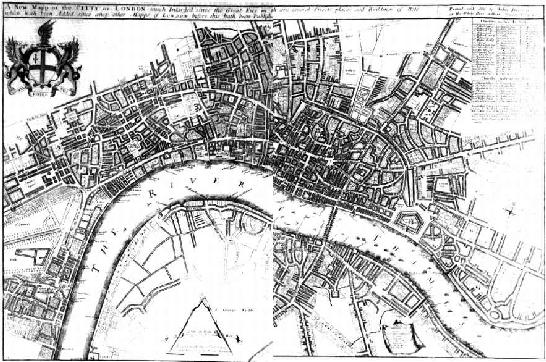

ENDPAPERS: Details from a panorama of London and Westminster c. 1700 (Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should like to thank my good friend Tim Hely Hutchinson, who has shown interest in this project from the start. I owe a debt of gratitude to my editor, Roland Philipps, for his belief in me and for giving me this opportunity to publish my first book. He has been kind and supportive throughout. I am grateful to the other members of the Hodder & Stoughton team for their enthusiasm and professionalism.

My thanks are due to my agent, Maggie Pearlstine, and to Matthew Bayliss and Toby Green, who have all been unstinting in their efforts on my behalf. I am grateful to Professor Lisa Jardine for steering me towards London in the eighteenth century. Thanks also to my friend Jane Ashelford for lending me her expertise on the dress of the period and on the picture research. As ever, she made it fun. Thanks to Jerome Boyd-Maunsell for his assiduous research at a couple of crucial moments.

This book would not have been possible without the help of the staff and superb collections in the London Library, Guildhall Library, the British Library and its Newspaper Library at Colindale, Senate House Library in the University of London, the Greater London Record Office at Clerkenwell and Lambeth Palace Library. Special thanks go to Mr Jeremy Smith and Mr John Fisher in the Prints and Maps Section at Guildhall Library. Mr Ian Murray at the Worshipful Company of Barbers kindly showed me their account books for the period, and Mr S. W. Massil at the Huguenot Society Library at University College London was most helpful in providing me with material.

I am most grateful to Dr Thomas Stuttaford for his advice on disease, and to my father, Dr John Waller, for his lengthy explanations of the same. Any howlers there are my own. I wish to thank Barry Turner and Tony Rennell for giving their valuable time to read the script and for their helpful comments and criticism.

Above all, I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to Brian MacArthur for his endless patience, encouragement, good humour, emotional and

practical support, and advice on how to write. He has listened to hours of what Daniel Defoe thought, and what Londoners before us said and did. It may now be possible for him to venture out with me without being treated to a description of the contents of the Fleet Ditch or the whereabouts of plague pits on an innocent expedition to dinner.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

... the chiefest emporium, or town of trade in the world; thelargest and most populous, the fairest and most opulent city atthis day in all Europe, perhaps the whole world

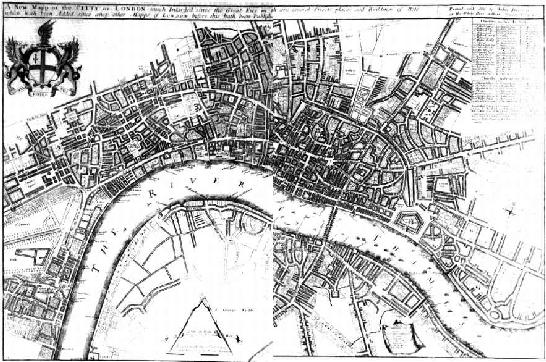

L ondon in 1700 was the most magnificent city in Europe. It took its beauty from Wrens skyline of churches, especially as viewed from the river. Dominating the city, the new St Pauls rested on its hilltop nearing completion. Only the dome was outstanding, prompting the wag Ned Wards analogy, As slow as a Pauls workman with a bucket of mortar. The River Thames was the artery of the metropolis, the wide thoroughfare dotted with thousands of pleasure craft and red and green passenger boats plying their trade. London Bridge with its density of houses and souvenir shops was the only bridge linking the north and south banks. And below it at the Port of London the ships lined up like a floating forest to unload their cargoes from the furthest corners of the world. Only a few miles away the hills of Hampstead and Highgate provided a reassuring rural backdrop to the thriving metropolis at their feet.

The capital dominated the kingdom to an extent that it has never done before or since. It was home to at least 530,000 people one in nine of the entire population while the second city, Norwich, had a population of 30,000. Not only did so many of William Ills subjects live in London, but the city impinged on the lives of many more. It was a magnet to all classes. Aristocracy and gentry flocked to London to be seen at court, to attend parliament, to settle their legal affairs, to enjoy the season and arrange marriages for their children, and to shop. London was a shoppers paradise, a great emporium of goods for its hungry consumers. The booming newspaper industry in Grub Street found a ready market in Londons coffee-houses where everything was up for discussion. London was the centre of a lively publishing trade, the theatre and music. Visitors absorbed its ideas and culture and disseminated them to all parts of the kingdom.

The Thames was Londons main highway, dotted with thousands of passenger boats and pleasure craft. Below London Bridge ships queued up like a floating forest to unload their cargoes (Guildhall Library, Corporation of London)

But this great city could not sustain itself. The mortality rate was higher than it had been a century previously. In any year there were more burials than christenings. One in three babies died before the age of two. Only one in two of the survivors passed the age of fifteen. Adults in their twenties and thirties, often family breadwinners, were particularly vulnerable. The streets were open sewers, the drinking water was contaminated, the stink of decaying refuse and overflowing graveyards was pervasive, houses did not have the conveniences of running water or flush lavatories and anyway, there was no understanding of basic hygiene. The atmosphere was thick with sulphurous coal smoke belching out of thousands of domestic and industrial fires, begriming the inhabitants and stultifying the gardens.

Tuberculosis was widespread and a particularly virulent strain of smallpox cut a swathe through the densely packed population. Medicine was largely helpless in the face of disease and a broken limb could be the harbinger of infection and death. It is not surprising, therefore, that native-born Londoners were chronically sick and of poor constitution, and the metropolis needed a constant influx of more robust migrants from the provinces. About 8,000 young people from all parts of the kingdom and as far away as Ireland poured in every year, attracted by the promise of wages 50 pet cent higher than anywhere else.

Next page