Maureen Waller - Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England

Here you can read online Maureen Waller - Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2013, publisher: St.Martins, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England

- Author:

- Publisher:St.Martins

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Brian, who made it possible

and Charles Spicer, who loves English history.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank my agent, Jonathan Lloyd, and my publishers, Roland Philipps and Charles Spicer, for their input and enthusiasm for this project. I am grateful to Morag Lyall for copy-editing the script, and to Rowan Yapp and the rest of the team at John Murray. I also wish to thank those who were kind enough to give me confidential interviews to discuss our present Queen.

Enormous thanks, as ever, go to my husband, Brian MacArthur, for his boundless support. He has lived with the six queens for far too long.

Introduction

Famous have been the reigns of our Queens. Some of the greatest periods in our history have unfolded under their sceptre

Winston Spencer Churchill, 1952

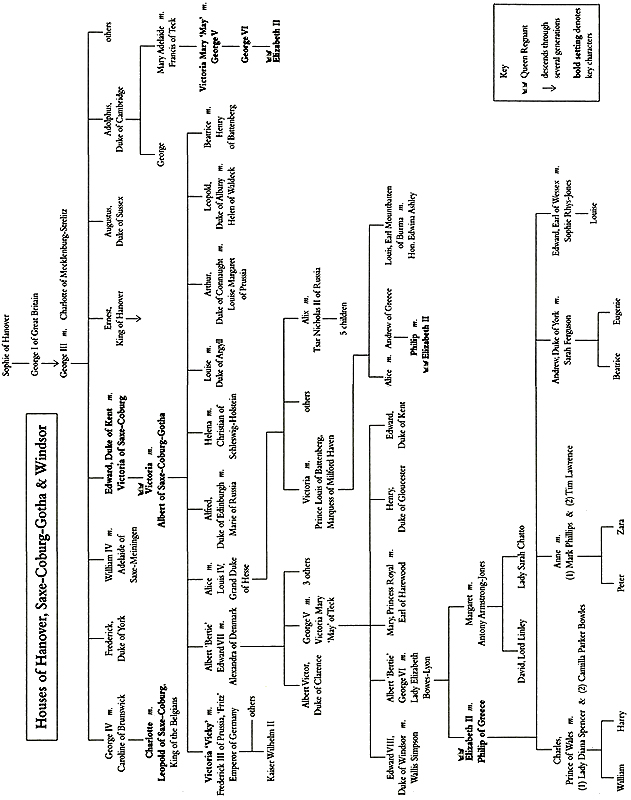

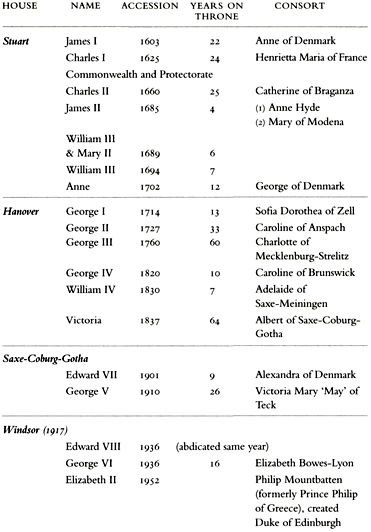

T HE ENGLISH LIKE Queens, the old Duchess of Coburg remarked cheerfully when she received news of the birth of her granddaughter, the future Queen Victoria. Indeed, by the early nineteenth century the English greeted the accession of a young female sovereign with relief. Victorias sex was very much to her advantage. Even in 1936, the year of the abdication crisis, the nation contemplated the eventual succession of the young Princess Elizabeth with happy anticipation, assuming she would emulate the qualities of her great-great-grandmother Victoria, while, in the aftermath of the Second World War, it was optimistically believed she would recreate a new Elizabethan age.

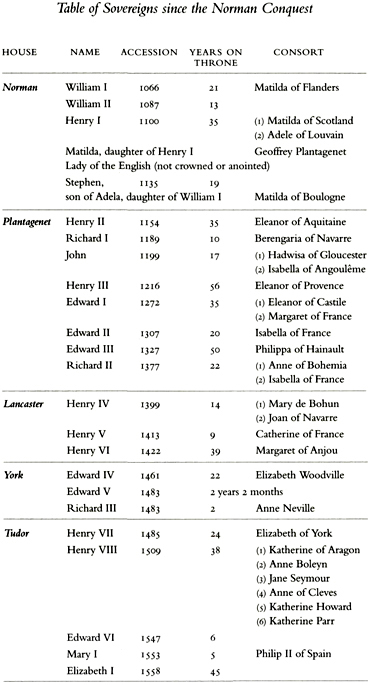

It had not always been so. England had no Salic law, barring a woman from the throne, but in practice the idea of female sovereignty was anathema. It was assumed that a female succession would plunge the country into civil war, as, indeed, it had when in the early twelfth century Henry I had died, leaving the crown to his daughter, Matilda. Although Henry had had his barons swear to accept her, and Matilda, who had been married to the Holy Roman Emperor, was no ingnue, the hereditary principle was not yet established, and it was easy for her cousin Stephen one of the boys, as it were, and not even the eldest son to snatch the crown.

Great by birth, greater by marriage, greatest in her offspring ran the epitaph for Matilda, who was never crowned or anointed queen. Nor did she ever call herself Queen. Possibly she thought the term, derived from the Saxon cwen, inappropriate, since hitherto it had applied only to queens consort, or possibly she hesitated to call herself Queen before a coronation had taken place. At any rate, the title she used was Lady of the English. There can be no clearer indication than her epitaph that as a woman she was seen merely as a vessel through whom the right to the crown would pass from one male to another, from her father Henry I to her son, Henry II. As she was a woman, it was assumed she would be unable to fulfil a kings primary function that of active military leader even though for nineteen years she courageously and determinedly fought her cause.

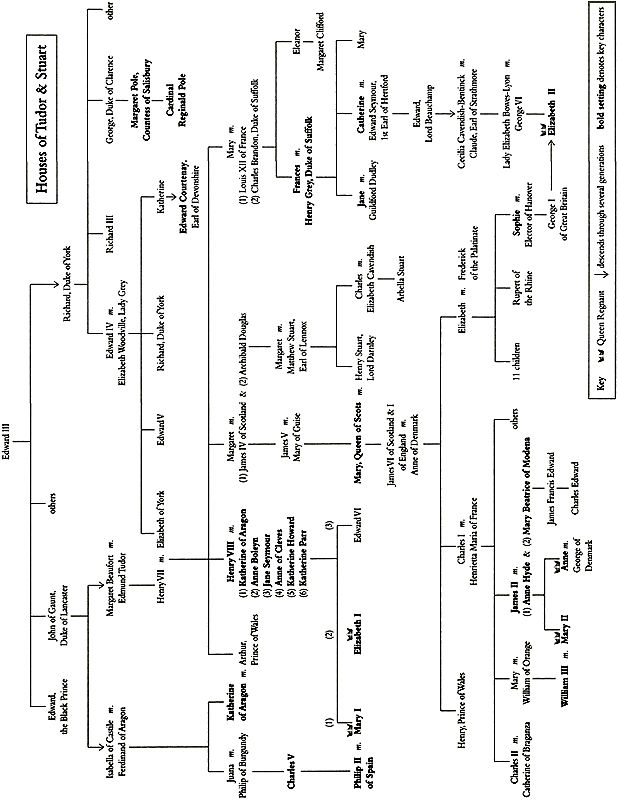

Four centuries later Henry VIII was confronted with the same problem, since his wife had failed as he saw it to provide him with a son. In theory, his daughter Mary could have fulfilled the same role as Matilda, a vessel to be used for the perpetuation of a masculine dynasty, had Henry married her off early enough. Indeed, Henrys own claim to the throne derived from two women: his grandmother, Margaret Beaufort, and his mother, Elizabeth, representing the rival claims of Lancaster and York, both of whom had ceded their rights to the men. Unfortunately, Henrys mind was far too conventional to accept the idea of a female succession and he failed to see the possibilities before him.

For someone as macho as Henry VIII, a daughter was a dent on his manhood, a deep injury to his self-esteem and hence to the glory of the monarchy, of which he was the personification. He would overturn Church and state to get a son, but, ironically, he was still succeeded after the six-year minority of Edward VI by two daughters. If the first failed to confound the prejudice against female rule, the second, Elizabeth I, was arguably the greatest sovereign in our history.

Contrast the childhoods of the first two Tudor queens regnant, Mary I and Elizabeth I, with the cocooned existence of the future Elizabeth II in the twentieth century, recalled in the saccharine account of Crawfie, her governess. Henry VIII threatened to chop off his daughter Marys head if she did not submit to his will, declaring her mothers marriage by Gods law and mans law incestuous and unlawful and herself a bastard. By the time she was three, Elizabeths status had changed from inheritrix of England to bastard; at thirteen, under suspicion of treason, she pitted her wits against the Council, and won; by the time she was twenty-one she was her sisters prisoner in the Tower, under threat of death. Their cousin, Lady Jane Grey, proclaimed Queen but never crowned and anointed, was only seventeen when she went to the scaffold, the innocent victim of ambitious and unscrupulous schemes to usurp the crown in her name.

Mary I and Elizabeth I came to the throne at a time of enormous religious upheaval. Everything that had brought comfort in previous centuries the age-old traditions of the Church, which embraced kings, nobles and commoners in the whole body of Christendom from the cradle to the grave and beyond had been stripped away, just as the reassuringly familiar figure of the King was replaced by a woman. How to assuage the anxiety that female rule generated, and how were these female sovereigns to overcome the drawbacks of their sex?

A tradition reaching back to Aristotle held that women were morally and physically inferior to men and therefore unfit to rule. The prejudice was strongly embedded in Christianity. The traditional Pauline doctrine of the Church I gyve no licence to a woman to be a teacher nor to have authorite of the man, but to be in silence had applied to queens consort as well as commoners. Indeed, it was Matildas authoritative personality that earned her the reputation of being proud and alienated the Londoners, whose support was crucial if she was to be crowned. The preponderance of queens regnant and female regents in the mid sixteenth century, in England, Scotland, France and the Low Countries, coinciding with intense religious conflict, fuelled the debate.

John Knoxs bitter diatribe, The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women, was a vicious attack on female rule generally, although specifically targeted at three Catholic queens, among them Mary Tudor. It is a thinge most repugnant in nature, that women rule and governe over men, he ranted, that a woman promoted to sit in the seate of God, that is, to teache, to judge or to reigne above man, is a monster in nature, contumelie to God, and a thing most repugnant to his will and ordinance. In Knoxs world, authority was equated with maleness; femaleness and rule were mutually contradictory.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England»

Look at similar books to Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sovereign Ladies: Sex, Sacrifice, and Power--The Six Reigning Queens of England and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![of Twitter @queen_uk - Still Reigning: [of Twitter @queen uk]](/uploads/posts/book/224535/thumbs/of-twitter-queen-uk-still-reigning-of-twitter.jpg)