The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Roland Philipps

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Enormous thanks, as ever, go to my husband, Brian MacArthur, whose idea it was for me to venture into the twentieth century, for his endless patience, wisdom, humour and support.

I should like to thank Jonathan Lloyd, wonderful agent and dear friend, and Roland Philipps, inspiring publisher, for their unfailing enthusiasm, dedication and kindness. I thank Lizzie Dipple at John Murray for her sympathetic assistance and attention to detail and Morag Lyall, who has done a splendid job copy editing all three of my books.

I wish to thank Mr Noel Mander for kindly giving permission to use the drawing on the endpapers, which was executed by his friend, the late Cecil Brown.

I am grateful to Professor Peter Hennessy and Mr Tom Pocock for generously giving their valuable time to reading sections of the script and offering helpful suggestions.

The historian of London is extremely fortunate in the wealth of material at her disposal and I wish to thank the staff of the following libraries and institutions for their helpful service: The Imperial War Museum, the National Archives, the Guildhall Library, the British Library and the Newspaper Library, the London Metropolitan Archives, the Trustees of the Mass-Observation Archive, University of Sussex, the London Library, the BBC Written Archives Centre, The Times Archives, the British Film Institutes National Film and Television Archive, Camden Local Studies and Archives Centre, Hackney Archives, Kensington and Chelsea Local Studies Library, Southwark Local Studies Library, Tower Hamlets Local History Library and Archives, and Westminster Archives Centre.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and I should like to thank all those who have kindly granted permission to use quoted material.

Maureen Waller

London, October 2003

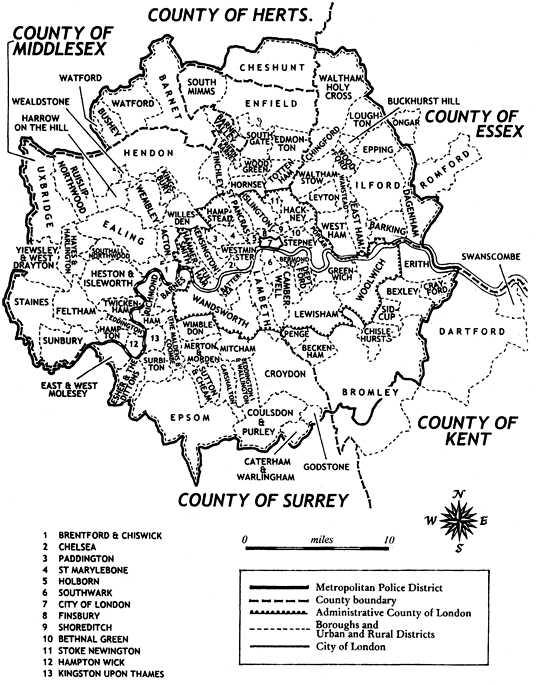

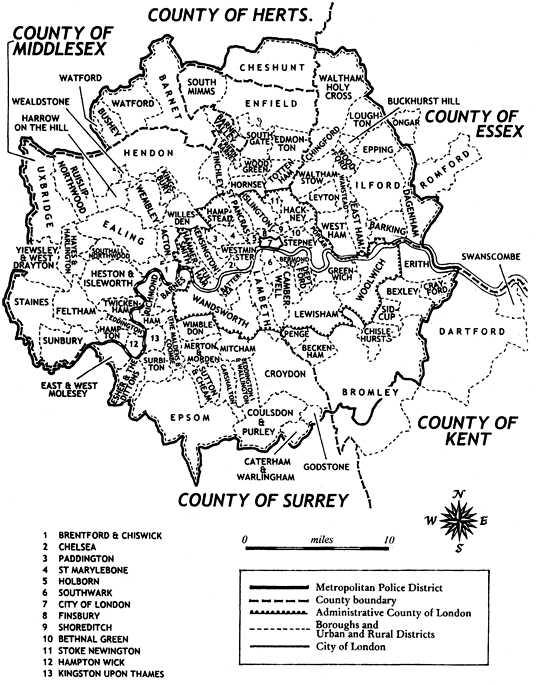

Ministry of Home Security

Composition of Groups in Region No 5 London Region

GROUP 1

Chelsea

Fulham

Hammersmith

Kensington

Westminster

GROUP 2

Hampstead

Islington

Paddington

St Marylebone

St Pancras

Stoke Newington

GROUP 3

Bethnal Green

City

Finsbury

Hackney

Holborn

Poplar

Shoreditch

Stepney

GROUP 4

Bermondsey

Deptford

Greenwich

Lewisham

Woolwich

GROUP 5

Battersea

Camberwell

Lambeth

Southwark

Wandsworth

GROUP 6A

Cheshunt

East Barnet

Edmonton

Enfield

Hornsey

Southgate

Tottenham

Wood Green

GROUP 6B

Barnet RD

Barnet UD

Finchley

Friern Barnet

Hendon

Potters Bar

GROUP 6C

Acton

Bushey

Ealing

Harrow

Ruislip

Southall

Uxbridge

Wembley

Willesden

GROUP 6D

Brentford

Feltham

Hayes

Heston

Staines

Sunbury

Twickenham

Yiewsley

GROUP 7

Barking

Chigwell

Chingford

Dagenham

East Ham

Ilford

Leyton

Waltham Holy Cross

Walthamstow

Wanstead

West Ham

GROUP 8

Beckenham

Bexley

Bromley

Chislehurst

Crayford

Erith

Orpington

Penge

GROUP 9A

Barnes

Epsom & Ewell

Kingston

Malden & Coombe

Richmond

Surbiton

Wimbledon

Esher

Merton & Morden

GROUP 9B

Croydon

Beddington & Wallington

Mitcham

Sutton & Cheam

Banstead

Carlshalton

Coulsdon & Purley

(TNA/HO 198)

LONDON REGION

Prelude

Through the long war, from beginning to end, London has been the wedge thats kept the door of freedom open

Macdonald Hastings

A visitor to London towards the end of 1944 would not be seeing the city and its people at their best. The first impression was one of grimy, grey drabness. Buildings black with soot cried out for a lick of paint. Boarded-up windows presented a blank face to the world. Mean terraces, with now and then a gap, fizzled out in piles of rubble. Acres of bomb sites and bricks, bricks meticulously counted and piled up: so many bricks in a devastated landscape. After five years of war, the people looked tired and worn. There they were in their shabby clothes, queuing for buses, or walking purposefully along, not bothering to give the bomb sites a glance. Women holding string bags stood patiently in long lines outside shops, resignation on their faces. If he closed his eyes the visitor became more conscious of the all-pervasive smell. It was of coal smoke in the damp chill, but something else too. Dust! Dust so acrid you could taste it in the mouth.

London was no longer filled with the buzz and excitement of thousands of Allied and foreign servicemen, as it had been in the build-up to D-Day, but there were still plenty of troops on leave. The white helmets of the American military police, known as the Snowdrops, could be spotted everywhere, keeping an eye on any of their men propping up walls or slouching along, the worse for drink. Wherever the GIs were, the good-time girls were never far away. In Piccadilly Eros was no longer the centre of attention: the god of love had been evacuated with thousands of Londoners mothers and children, the old and the sick. In his place stood a gigantic ugly box covering the empty plinth, a billboard urging people to buy Savings Certificates firmly plastered to its side. The crowd was drawn there all the same.

Just a few steps away on Shaftesbury Avenue stood Rainbow Corner, the most famous of the American Red Cross Clubs in town, where the American visitor would find his home from home. Groups of GIs would mass on the pavement outside, deciding how to spend their time: a dive straight into the flesh market in Piccadilly Circus, or a pub crawl, to get drunk on the warm, weak beer? Those in the know might nip round the corner to the back bar of the Caf Royal, where whiskey from neutral Ireland was in plentiful supply. Otherwise, spirits were hard to come by. Or perhaps a trip to the famous Windmill Theatre, whose proud boast was that it never closed. Never clothed, more like. Here pretty girls in chorus lines were still indefatigably kicking their legs and nudes stood stock still, impassively ignoring the ear-splitting bangs and vibration of falling doodlebugs and rockets.

Step into the hall of Rainbow Corner and the visitor was instantly reminded why he was here at all, part of the friendly occupation force passing through London. An arrow, pointing vaguely east towards Leicester Square, bore the inscription: Berlin 600 miles. Another, pointing in the direction of Regent Street, said: New York 3,271 miles. There was everything here for his comfort. The voice of Bing Crosby blended with the clinking of Coca-Cola bottles, and over all there was a haze of smoke from copious supplies of American cigarettes. A thousand couples could jitterbug in the dance-hall. There were billiards, table tennis and pin-tables. There was a shoe-shine parlour, a letter-writing service and a juke box. One large comfortable lounge held a piano and plenty of armchairs, the other a big selection of classical records and a radiogram. There was a hobbies room, regular cabarets, weekly boxing shows and nightly free cinema. The GIs even had their own newspaper, the Stars and Stripes, packed with action from the battle zone, sports features and news from the States. Although it was printed on the presses of The Times at Blackfriars, there was little mention in the Stars and Stripes of the host city, London.