Contents

About the Author

Philip Ziegler was born in December 1929 and educated at Eton and New College, Oxford, where he gained first class honours in Jurisprudence. He then joined the Diplomatic Service and served in Vientiane, Paris, Pretoria and Bogota before resigning to join the publishers William Collins, where he was editorial director for over fifteen years. His books have included biographies of William IV, Melbourne, Lady Diana Cooper, Mountbatten, Edward VIII and Harold Wilson, as well as a study of the Black Death. He lives in London.

List of Illustrations

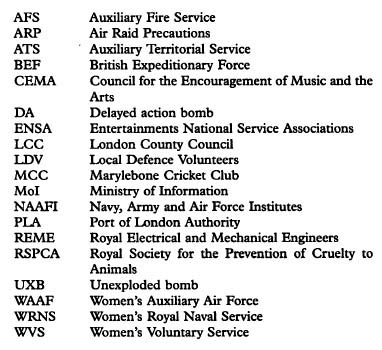

Abbreviations Used in Text

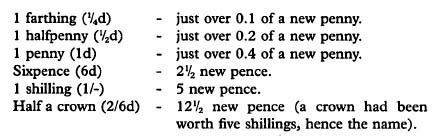

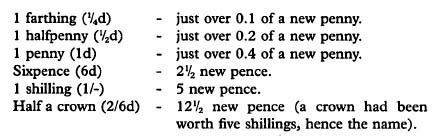

Table of Comparative Values

THE POUND STERLING was decimalised in 1969; previously it had been divided into 20 shillings (20s) and 240 pence (240d). A shilling, which comprised 12 pence, was written 1/-; one and a half shillings would have appeared as l/6d. The main units in the old currency, with their equivalents in new pence, were:

Comparisons between the values of currencies at different periods are often misleading and always need cautious handling, but the latest figures from the Bank of England (for which I am indebted to Sir Peter Petrie) suggest that if the pound sterling in the summer of 1994 be taken as purchasing 1 worth of goods, the corresponding unit in the summer of 1939 would have bought 25.4 times as much. Inflation rose sharply in late 1939 and in 1940, but the purchasing power of the pound calculated on the same basis stabilised at a little under 20 at the beginning of 1941 and remained between 19.8 and 19.5 for the rest of the war. As a rough-and-ready guide, figures should be multiplied by 25 at the beginning of the war to arrive at the contemporary purchasing power, and by 20 from the beginning of 1941.

Introduction

MY AMERICAN PUBLISHERS first suggested I should write this book. They had been responsible for a very interesting study of Washington during the Second World War, and thought that it would be a good idea to accompany it by a book about a city closer to the firing line. At first I was doubtful. The subject had been covered before, and though I was confident that there would be plenty of new material I was not sure that I would find it easy to steer a course between the gullible acceptance of all the legends peddled about wartime London and a revisionist determination to reject the lot of them.

I soon found that I had mis-stated the problem. The subject was so vast, the material emotionally so super-charged, that everything was true. Individual stories might not be verifiable, yet in essence every legend illustrating the courage, the self-sacrifice, the dignity, the humour of Londoners under fire could readily be substantiated. But so could every charge of snobbishness, selfishness, the spirit of sauve qui peut. London between 1939 and 1945 was a theme bursting at the seams with spectacular vitality. It was one of the great stories of the world. Like all great stories it had its seamy side. As in all great stories the web of often contradictory detail sometimes concealed but never obliterated the simple, powerful drama that underlay them.

As a biographer, it was Londoners rather than London that most concerned me. So far as possible I have told the story through the words of contemporary Londoners, written in diaries or letters or taken from conversation. The diaries published of prominent personalities such as Harold Nicolson or Hugh Dalton, or unpublished of Lord Woolton or Euan Wallace have been of great value, but I have relied even more on the letters or diaries of ordinary people: George and Helena Britton, a retired couple living in Walthamstow and writing weekly letters to their daughter in California; Hilda Neal, who ran a small typists shop in South Kensington; Gwladys Cox, a middle-aged widow from West Hampstead. No less useful have been the records of Mass Observation, that regiment of skilled eavesdroppers who recorded the comments of Londoners throughout the war.

I have been able to add little by way of personal record. As a boy on my way to school I frequently traversed London and towards the end of the war I sometimes spent a night there, but such bombs as I heard fell on or around Southampton. I cannot claim, even in a small way, to have shared the experiences of the capital. Perhaps it is just as well: human memories are frail and I suspect that after fifty years I would have edited or enhanced my recollections beyond recognition. Not everyone is so fallible. Since I began work on this book I must have spoken to several thousand people 3000 at least who had some direct experience of wartime London. To list them all would take several pages and serve little purpose. I hope they will accept this as a statement of my gratitude.

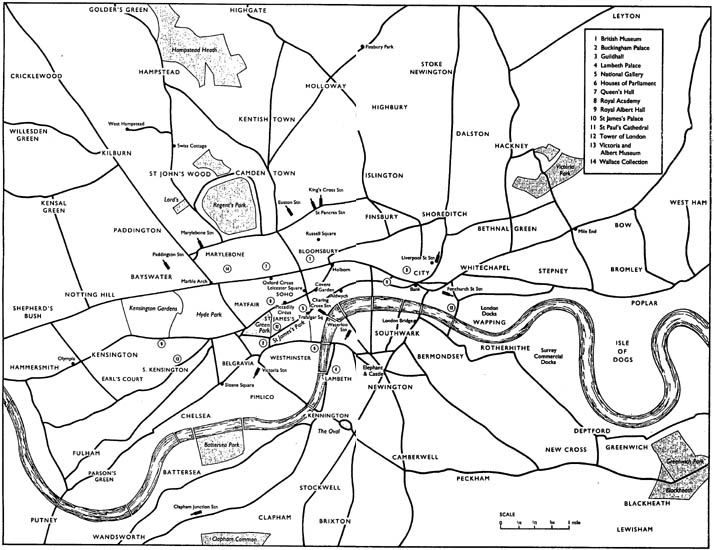

All books pose problems of delimitation; a study of London during the Second World War sets some particularly complex challenges. First, what is London? Before the war the Greater London or Metropolitan Police area covered 700 square miles; the Greater London Town Planning or London Transport area 2000 square miles; the County of London 116; the City of London 1; the London Telephone area 1200; the London Postal area 232; the London Electricity District 1840; the Metropolitan Water Board area 573; the London Main Drainage area 159. With war still more entities were created: the London Civil Defence Region, for the purposes of the Fire Watchers Order, comprised the administrative County of London; the county boroughs of Croydon, East Ham and West Ham; all county districts situated wholly or partially within the Metropolitan Police district with the exception of the borough of Watford, the urban districts of Caterham and Warlingham, the rural districts of Hatfield, St Albans and Watford.

When people referred loosely to London or Londoners, which of these did they have in mind? Almost certainly none. They knew what they meant by London, but did not seek to define it. To be a Londoner was and is more a state of mind than a question of geographical location. If pressed, I would probably fall back on the traditional LCC definition of Greater London as being any area within fifteen miles of Charing Cross, but I am aware that I have been guilty of inconsistencies and occasional transgressions of my own rule. I know what I mean by London and hope that readers will excuse some blurring of its exact demarcation.

Another problem is to distinguish between those things that pertain exclusively to London and those of wider application. It would be absurd to describe wartime London without mentioning rationing or the radio show ITMA, yet both of these were experienced as vividly in Glasgow or rural Devon. I have not excluded anything on the grounds that it was as much national as local, but have so far as possible described it as it seemed to those in London. It is possible that a Glaswegian or a Devonian would have had the same reaction, but the voices I record are those of Londoners.

My debt to published books is obvious. In the introduction to the bibliography I have tried to pick out those which I found of special value. Every book I list, however, every newspaper cited, every official document studied at the Public Record Office, is in some way reflected in my work.