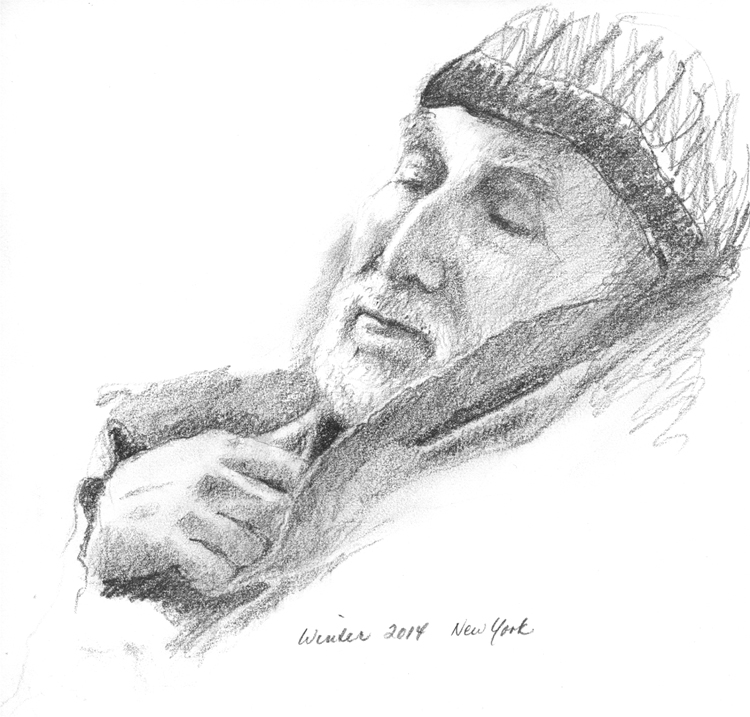

FOUAD AJAMI

(September 18, 1945June 22, 2014)

The Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, founded at Stanford University in 1919 by Herbert Hoover, who went on to become the thirty-first president of the United States, is an interdisciplinary research center for advanced study on domestic and international affairs. The views expressed in its publications are entirely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, officers, or Board of Overseers of the Hoover Institution.

www.hoover.org

Hoover Institution Press Publication No. 623

Hoover Institution at Leland Stanford Junior University, Stanford, California 94305-6010

Copyright 2014 by the Board of Trustees of the

Leland Stanford Junior University

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holders.

The Hoover Institution would like to thank The New Republic, Foreign Affairs, and TriQuarterly for their cooperation and consent to the republication, in slightly adapted form, of essays and articles that originally appeared in their journals. Source information for any previously published essay can be found in a footnote on the first page of the corresponding chapter.

Frontispiece sketch of Fouad Ajami is by Michelle Ajami.

For permission to reuse material from In This Arab Time: The Pursuit of Deliverance, by Fouad Ajami, ISBN 978-0-8179-1494-3, please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of uses.

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8179-1494-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8179-1496-7 (e-pub)

ISBN 978-0-8179-1497-4 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8179-1498-1 (e-PDF)

The Hoover Institution gratefully acknowledges the following individuals and foundations for their significant support of the

HERBERT AND JANE DWIGHT WORKING GROUP ON ISLAMISM AND THE INTERNATIONAL ORDER:

Herbert and Jane Dwight

Donald and Joan Beall

Beall Family Foundation

S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation

Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation

Stephen and Susan Brown

Mr. and Mrs. Clayton W. Frye Jr.

Lakeside Foundation

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

F ouad Ajami, who passed away on June 22, 2014, was a gifted scholar, teacher, writer, adviser, and public commentator. He was also a dear friend to me and many colleagues and supporters of the Hoover Institution. It is our distinct pleasure to present this profound collection of essays assembled personally by Fouad just prior to his death. I am confident the insights contained in this book will shed light on our understanding of the Middle East, but more importantly, affirm Fouads abiding convictions toward peace and freedom for all people. Many of Fouads lifetime achievements are noted at the end of these collected works.

Further, Fouad led an important working group at the Hoover Institution for several years with Hoover fellow Charles Hill, focusing on Islamism and the International Order and sponsored by Herb and Jane Dwight. The product of this significant effort is summarized later in this treatise.

JOHN RAISIAN

Tad and Dianne Taube Director

Hoover Institution, Stanford University

In Memoriam

Our Magus

Cut these words and they would bleed; they are vascular and alive; they walk and run

RALPH WALDO EMERSON

O ne dark December day I walked to the Union League on Chapel Street, early for lunch with Fouad Ajami, who was taking the train from Manhattan to New Haven. I settled in to look at a book while I waited for his arrival; bright flames silently flickered in the fireplace; through the high window Yales gray, stately Vanderbilt Hall loomed across the way. A half-hour passed as other diners arrived to fill the room. Then forty-five minutes. I craned my neck to survey the place. There was Fouad, alone at a table on the far side, happily holding a book; he had been there all along, coming in well ahead of me.

This is not the way we usually thought of Fouad: he was far more likely to be standing at a lectern, or on a television panel, or in seemingly constant travel, or in animated discussions with friends and adversaries alike. Here at the Union League I could see that he was not reading that book, he was thinking. He possessed a perpetual energy of mind; he was, as Emerson hoped for, man thinking, always in the sense of thinking as acting. That is why that scene in the Union League made an impression. Fouad resembled some erudite but intrepid Victorian-era gentleman contentedly at ease in his club chair yet poised to be off in a trice to the hellholes of the earth to accumulate the knowledge that civilization most needs to know.

When we first met, Fouad and I were both college teachers. But Fouad had many more dimensions than I. Every time, and it was often, that we talked about his role in the university and I in mine, it was clear that he felt hemmed in by the four walls of the seminar room. One fall semester he invited me to join him in teaching his class at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. He was a transcendent teacher, vitally exuberant, a challenging, loving mentor, clearly adored by his students. But he always had an audience of larger demographic magnitude on his mind, an American, Middle Eastern, and world population. He would soon give up his professorship to take up full-time his veritable vocation. Which was what? We have no entirely apt label for it. Like Emerson, he invented a career for himself alone. We can say that Fouad Ajami was the foremost example in our time of the lineage of intellectual-moral, thinker-travelers who from ancient times onward have illuminated the human condition and, as great writers and transfixing speakers, drawn lessons from it for us to contemplate and act upon. Yet even knowing this much about him, Fouads true significance has yet to be understood.

Fouad and his philosophical-historical forebears took on the simplest yet most perplexing challenge: what is going on, and why? The peoples of the world have organized themselves in ways multifarious beyond number. How are these differing systems and their cultures by which they define themselves structured, and why does it matter? Can such diversity ever interact coherently, productively, and peacefully? Is one as good as any other? Or can we be judgmental and conclude that some, or one, is preferable?

Fouad was naturally gifted in this role, and he educated and honed his gifts incessantly: he was both an insider and an outsider wherever he wentexcept in his home village, but he knew that You cant go home again. He was an Arab with a family name that conveyed Persian-ness. He was a Shia, a faith constructed on loss, relegation, and righteous victimization; as a believer, he was both reverential and skeptical. In appearance, voice, and demeanor, he seemed the epitome of all things Middle Eastern, yet he was a nonhyphenated American patriot. He was poet, philosopher, statesman, historian, bon vivant, and, to his Jewish following, mensch.

Next page