Table of Contents

TO JUDY

AND

TO OUR FRIENDS

LEONARD AND JOAN

Praise for STORM FROM THE EAST

Informed... nuanced... a succinct and lucid account of the centuries-old conflict between the Arab world and the Christian West."

The Economist

A fast-paced history of the conflict between Arabs and the Western world... [Storm from the East] is helpful to anyone seeking a highly readable overview of the events and issues that shape U.S. engagement with the Arab world."

The Dallas Morning News

Having covered the Middle East for three decades, Milton Viorst has the eye of the historian but the brevity of the reporter, and his concise book sweeps across the centuries to explain the disparities between values and viewpoints of the Islamic East and Christian West. His chronicle helps to overcome a mutual sense of differentness that has sometimes been the only link between two worlds."

JIMMY CARTER

I wish President Bush had had the benefit of Storm from the East before stumbling into a war in which so much blood has been spilled. This is an illuminatingand deeply disturbingaccount of the ages-old conflict between Christian and Muslim civilizations. Iraq emerges as one episode in this long struggle. It is remarkable how Milton Viorst has managed to reduce a struggle so complex to such lucid prose."

DANIEL SCHORR, senior news analyst, National Public Radio

Storm from the East reminds readers saturated by slogans about terrorism and jihadism that Arab hostility to Western intrusion has a longer political history than the current conflict in Iraq. Sadly, blissful ignorance of that history is one of the root causes of Americas ongoing and increasingly tragic military plunge into the Middle Eastern quagmire."

ZBIGNIEW BRZEZINSKI, former director, National Security Council

Viorst calmly but devastatingly explains the historical reasons that our adventure in Iraq was doomed from the start."

San Jose Metro

PREFACE

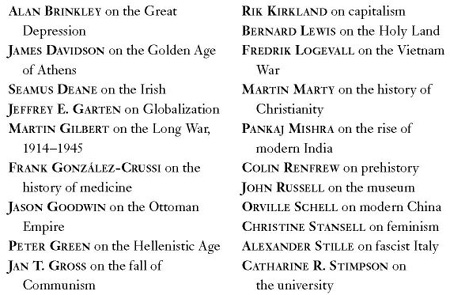

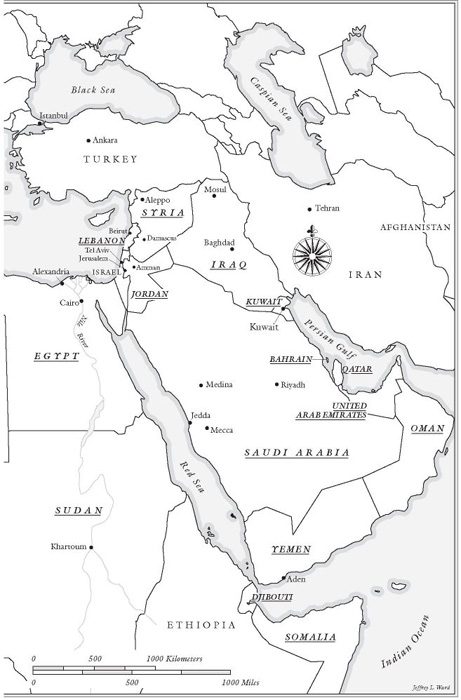

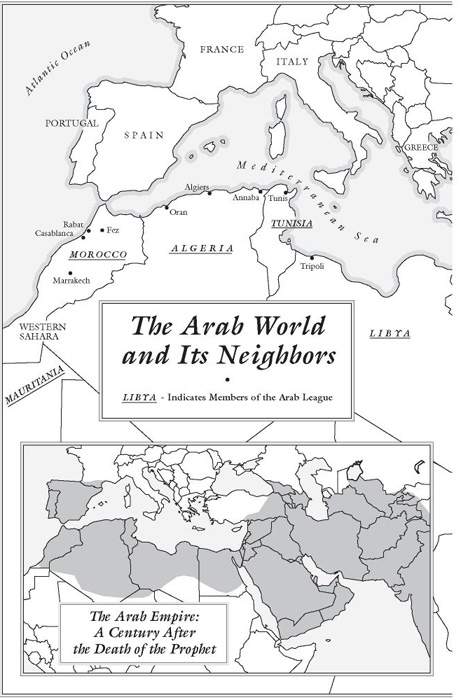

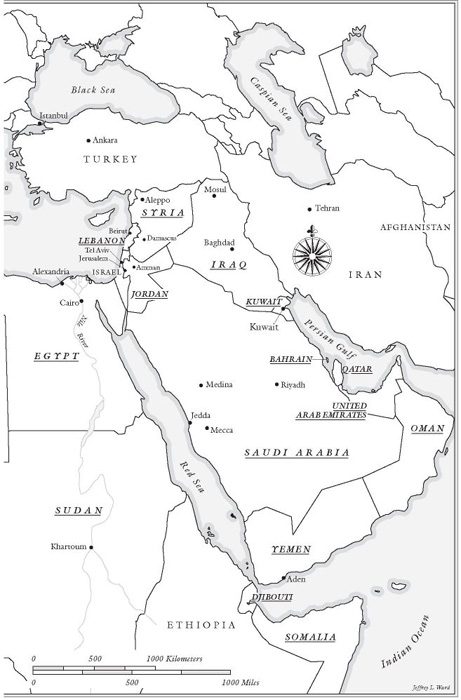

This book, within the larger canvas of Arab history, focuses on the centuries-old contest for dominance between the Islamic East and the Christian West. The contest started in the seventh century, when Islamic armies organized by the Prophet Muhammad spilled out of Arabia into lands that were overwhelmingly Christian. In a series of stunning victories, they advanced as far as the Pyrenees in the west and the Bosporus in the east. In just a few decades, they established the perimeter of what we now call the Arab world.

Since then, momentous events have transpired, marked by ebbs and flows but by few interruptions, in the conflict between two civilizations. The Crusaders seized Jerusalem in 1099, and a century later the Muslims took it back, freeing the Middle East from Western forces for six hundred years. In the fifteenth century, Christian armies drove the last Muslims out of Spain, ending the threat to Europe on one of its flanks, only to face a greater threat from the Ottomans, who inherited the Arabs sword, from the other flank. The Ottomans in that era captured Constantinople, the last great Christian stronghold in the East, and swept over much of eastern Europe.

By the sixteenth century, the tide in the Muslim-Christian struggle had shifted again. The wealth that flowed into Europe from global commerce, much of it from the newly discovered Americas, became the engine of technological innovation, a sharp contrast with the intellectual and economic stagnation of the Islamic world. In 1571, Christian navies decimated the Ottoman fleet at Lepanto off the coast of Greece, ending the threat of Muslim control of the Mediterranean. In 1683, the Ottoman army was defeated at the gates of Vienna, initiating a steady retreat overland to the Muslim Middle East. By the eighteenth century, it appeared inevitable that, at the propitious moment, the West would direct an offensive against the Islamic heartland itself.

The moment came at the start of the nineteenth century, when Western powers, in competition with one another, began nibbling at the edges of the Ottomans Arab possessionsEgypt, North Africa, the Gulf. The practice was known as imperialism, and only the Europeans unreadiness to risk bloodshed by extending their rivalry to the Middle East granted the Ottomans a reprieve. Europes self-restraint ended with World War I, in the course of which the Ottoman Empire fell. For centuries, the empire had served as a barrier between the Arabs and the Christian West; its collapse opened the gate to Europes conquest of the Arab world. Within a few years, the Wests political domination of the Arab region was joined to its quest for oil, but its efforts fed a commensurate growth of fiery Arab nationalism. Whatever the military mismatch, the West has not had an easy time subduing the Arabs. Americas war in Iraq, igniting an explosion of Arab nationalism, is the latest round in this long contest. To see it otherwise is to deny the evidence of history.

One clear lesson of the centuries of struggle is that both these civilizations possess enormous inner strengths. For the West to imagine it can impose its values on the East is a huge miscalculation. For the East to imagine the zealotry of its warriors can intimidate the West is nave. Another lesson is that neither has the power to choose the others course. Though the confrontation is likely to go on, both sides can profit, by lowering the stakes, from an extended lull. Notwithstanding its military superiority, unless the West accepts the Easts right to determine its own future, the bloodshed that currently marks the contest will continue. Both civilizations will clearly be the poorer for it.

That is the message of this book.

Currently Available

Forthcoming

I

MEMORY 6221900

Americas war in Iraq, from its start, did not go as President Bushs administration had predicted. Though the U.S. army captured Baghdad and Iraqs other major cities easily enough, and encountered little resistance in abolishing the detested regime of Saddam Hussein, Iraqis did not greet Americas forces with the gratitude that they had been told to expect. Far from treating Americas soldiers as liberators, which is how they looked upon themselves, Iraqis regarded them as conquerors. It was a distinction for which most Americans were shockingly unprepared.

Frustrated, the American invaders believed they were being misunderstood. The leadership in Washington had proclaimed repeatedly that its quarrel was not with the Iraqi people but with Saddams regime. It had assured its soldiers of the nobility of their mission, not just to end a dangerous military threat but to wipe out tyranny and create the conditions for democracy. Wasnt that why the armies of their fathers and grandfathers had disembarked in 1944 in France, to a delirious welcome by the local population? In 1945, moreover, the defeated Germans and Japanese, taking for granted the victors benevolence, willingly established free and democratic regimes. So why were the Iraqis so hostile?

Next page