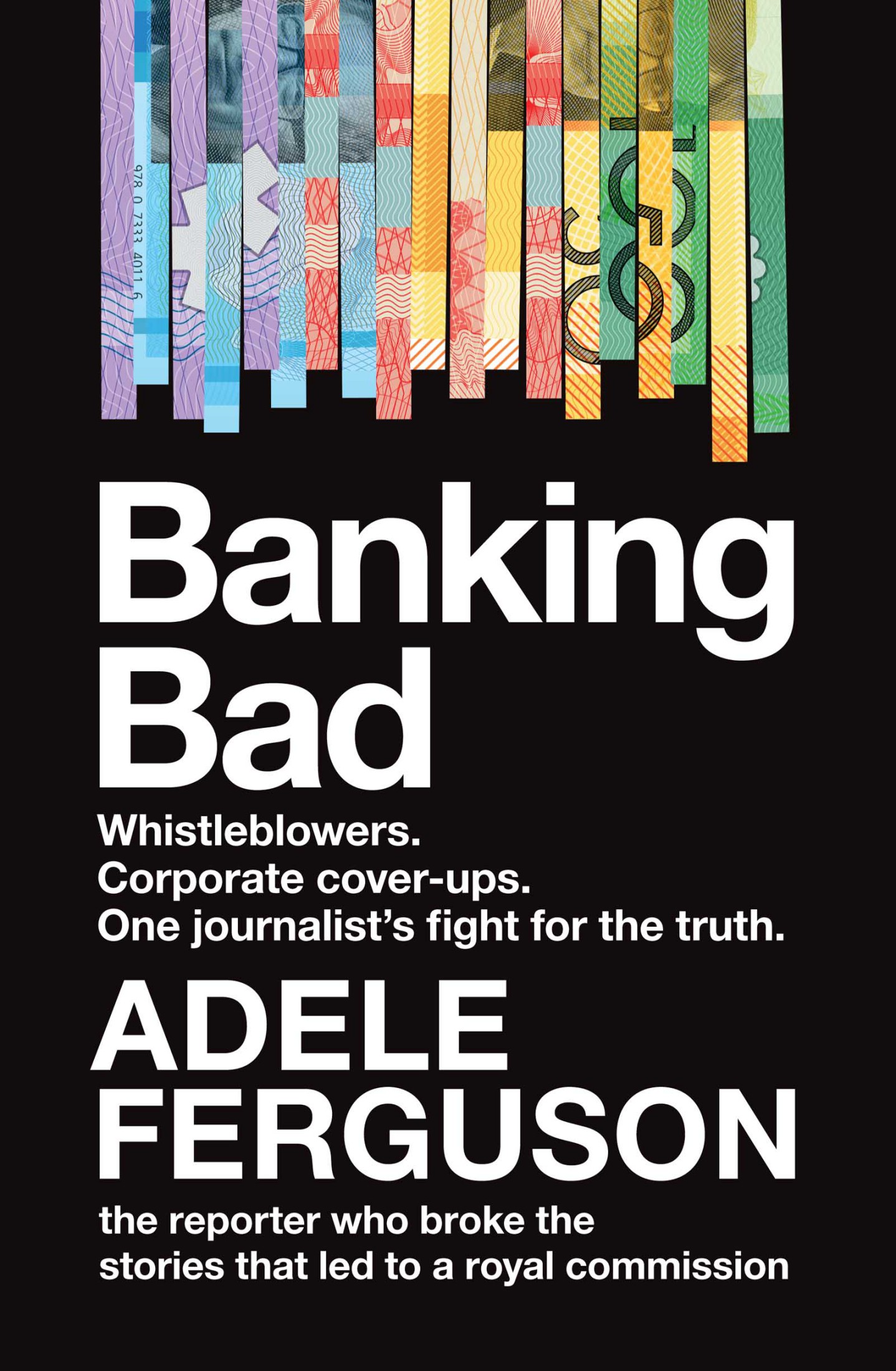

To those who choose not to stay silent

Contents

CAN YOU PLEASE GIVE me a call when youve got a minute, Adele? Its about the Commonwealth Bank. Its big. I have a whistleblower who wants to speak to you.

It was 4 April 2013 when I received this phone message from Nationals Senator John Wacka Williams. Id come to know and trust Wacka after Id written a series of stories that exposed some seriously dodgy behaviour in the insolvency industry, including fraud, standover tactics and links to the criminal underworld. An affable but hard-nosed politician, Wacka had received death threats and been the victim of smear campaigns after those investigations and had never flinched. This had cemented my deep respect for him. I hadnt thought anything could get much grubbier or more corrupt than liquidators and the insolvency industry, but Williams phone message would blow this assumption out of the water.

The call came as I was getting ready to head to China on a work trip to cover the annual Boao Forum for Asia, a conference that brings together business people, politicians and academics to discuss policy and economic issues of the day. Prime Minister Julia Gillard was attending, along with the recently appointed Chinese president, Xi Jinping. I called Wacka back and he gave me the phone number of the whistleblower, Jeff Morris.

In between packing and finalising a late visa application for China, I rang and spoke to Morris, whod worked for the Commonwealth Bank (CBA) until March 2013. He wanted to blow the whistle on CBAs malpractice; he also wanted to alert the public to the slowness of the countrys corporate regulator, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), to investigate allegations he had already made.

After our call Morris emailed me over one thousand pages of documents, which I printed out before racing to the airport, hoping I wouldnt be late for my flight. What he had told me during that phone call and the material he had sent would lead me to uncover and expose misconduct in one of the countrys most trusted and venerable institutions.

As I sat on the plane and went through the documents, I became increasingly shocked. They included internal bank emails, whistleblower correspondence with ASIC, and a series of customer files, which showed CBA had wilfully engaged in forgery, fraud and a management cover-up. The bank had put profit before people a theme I would become all too familiar with over the next five years as I investigated other well-regarded financial institutions.

CBA wasnt some shonky fly-by-night company no one had heard of; it was the so-called peoples bank. Established by the Commonwealth Government in 1911, it had been allowed into our childrens schools to sign up kids to savings accounts. It was an iconic institution that most Australians knew and trusted.

The most confronting document I read on that flight to China was a fax Jeff Morris had sent to ASIC warning it that CBA was engaged in a high-level conspiracy to conceal repeated material breaches, corruption and gross incompetence of the banks star financial planner, Don Nguyen, resulting in losses to clients of tens of millions of dollars. Those material breaches included forging clients signatures, failing to provide essential documents such as statements of advice, and giving inappropriate recommendations. The most telling detail was that ASIC had ignored Morriss tip-off and done nothing for sixteen months.

Here was a scandal that involved the most profitable company in the country, its number-one financial adviser, a management cover-up and a regulator that had failed to act. It had the makings of a crackerjack story.

*

As soon as I arrived back in Australia, I rang Wacka and organised a meeting in Sydney with Jeff Morris and some other people Jeff knew who had battled CBA.

Weeks later, on 1 June 2013, the first day of winter, the story I wrote sent a hurricane through the financial services sector when it appeared on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age. The public response to the article was phenomenal. It was the leading news item of the day, the next day and the next. Australians were appalled that CBA had shafted some of its most vulnerable customers and engaged in practices that were deceiving and illegal.

The initial articles focussed on CBA and one dodgy financial planner, but as the weeks went by the story got bigger. CBAs malpractice became a symbol of a toxic banking culture built on greed, targets and bonuses, where profits were put before people, and corporate regulators sat silent. Previous banking scandals had come and gone, but this one resonated with the public, and CBA couldnt fob it off as it had done in the past.

The banks power rested not just in the profound wealth they were producing but also in the deep connection between the banks and the political establishment. Former heads of treasury, premiers, Reserve Bank governors, ASIC commissioners and ministerial advisers had all joined their ranks, taking up seats on boards and other key positions of influence. The widespread, aggressive and successful lobbying by the banks over many years was not unrelated to these appointments. The extent of the interlinkages dwarfs any other sector. The meshing of the political class into the finance sector both reflects the power of the banks, and in turn contributes to the power of the banks.

But the Commonwealth Bank financial planning scandal pierced that veil.

Soon the story had multiple villains, hundreds of thousands of victims, and many superheroes. Jeff Morriss courage in blowing the whistle on what was going on at CBA made him one of those superheroes. He helped break the culture of silence and spurred other bank insiders to speak out. Many came to me.

A whistleblower from Macquarie Group contacted me with information about financial advisers cheating in professional development exams and misleading customers. A National Australia Bank (NAB) insider sent me an explosive cache of internal documents which revealed NAB had similar issues to CBA, including staff committing forgery and fraud as well as a cover-up by management. Then a whistleblower from the financial services giant IOOF Holdings sent me thousands of documents that disclosed misconduct, including insider trading, other types of market manipulation, misrepresentation of performance figures, and even the boss of its research division getting staff to cheat on his behalf in professional exams.

The Australian and New Zealand Banking Group (ANZ) was next. Documents I received revealed ANZ had bankrolled a high-risk, agricultural investment scheme, Timbercorp, which collapsed, with thousands of victims losing billions of dollars and owing massive debts.

When a call came from CBAs chief medical officer, Dr Ben Koh, that he was about to lose his job in the banks life insurance arm after becoming an internal whistleblower, it was a watershed moment. Dr Koh revealed that CBA was putting profit before sick and dying customers. He said CBA was rejecting legitimate insurance claims by relying on outdated medical definitions. It didnt get much lower than that.

In March 2016, I presented the story in a joint venture with The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald and in an episode of Four Corners, called Money for Nothing. In the program, Dr Koh described rampant misconduct, and a series of victims, some dying, told harrowing stories of fighting the bank after it had mercilessly knocked back their life insurance claims.

The revelations of Money for Nothing provoked outrage. It was clear that vast numbers of executives across the financial sector had lost their moral bearing. A parliamentary inquiry into the life insurance industry was set up and the government ordered ASIC to launch an immediate investigation.