Copyright 2018 by Tiffany Watt Smith

Cover design by Tracy Shaw; art Shutterstock

Cover copyright 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown Spark

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

littlebrownspark.com

twitter.com/lbsparkbooks

facebook.com/littlebrownspark

First Edition: November 2018

Little, Brown Spark is an imprint of Little, Brown and Company, a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Little, Brown Spark name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

ISBN 978-0-316-47029-2

E3-20181017-JV-PC

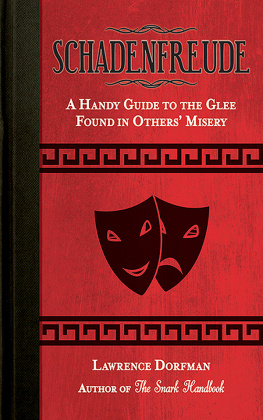

The Book of Human Emotions

To my brother, Tom

The blessed in the kingdom of heaven will see the punishments of the damned, so that their bliss will be that much greater.

St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae, written 12651274

Times I feel pleased at things going wrong for other people:

When a news correspondent gets tangled up in her scarf in strong winds on live TV.

Seeing an urban unicyclist almost collide with a parked car.

At the shops, when the person in front of me is rude to the cashier and then their card is declined.

When I hear about satnavs sending lorries down narrow country lanes where they get stuck.

When my coworker was training for a marathon, boring us all with his training plans and special diet, ostentatiously checking his Fitbit and tweeting his stats, wearing his tiny, shiny red running shorts into work, festooning said shorts over his desk chair to dry, stretching by the photocopier, talking about his groin injury, always smelling of sweat and then not completing his marathon.

Tattoo fails (no regerts!).

And once, in my twenties, when my effortlessly attractive friend got dumped.

Last Tuesday, I went to the corner shop to buy milk, and found myself pausing by the celebrity gossip magazines. And my first instinct, just in case someone was listening in on my thoughts, was to think: ugh, who buys those terrible magazines. But then I picked one up, just out of curiosity. There was the cellulite, the weight gain and loss, the bikinis riding up between the bum cheeks and bingo wings circled in red. My favorite story was an interview with a pop star, or perhaps she was a model, who lived in a giant luxury mansion. Now Im the sort of person who usually curdles with envy on hearing about someone elses luxury mansion. But this was different. The story was about how she was lonely. Tragically lonely following a tragic breakup.

I looked about, took the magazine to the till and counted out my change. There was a warm sensation working its way across my chest. I felt lucky. No, thats not it. I felt smug.

This is a confession. I love daytime TV. I smoke, even though I officially gave up years ago. Im often late, and usually lie about why. And sometimes I feel good when others feel bad.

WHAT IS SCHADENFREUDE?

The boss calling himself Head of Pubic Services on an important letter.

Celebrity Vegan Caught in Cheese Aisle.

When synchronized swimmers get confused, swivel the wrong way, and then have to swivel back really quickly and hope no one notices.

The Japanese have a saying: The misfortunes of others taste like honey. The French speak of joie maligne, a diabolical delight in other peoples suffering. The Danish talk of skadefryd, and the Dutch of leedvermaak. In Hebrew enjoying other peoples catastrophes is simcha la-ed, in Mandarin xng-zi-l-hu, in Serbo-Croat it is zlradst and in Russian zloradstvo. More than two thousand years ago, Romans spoke of malevolentia. Earlier still, the Greeks described epichairekakia (literally epi, over, chairo, rejoice, kakia, disgrace). To see others suffer does one good, wrote the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. To make others suffer even more so. This is a hard saying, but a mighty, human, all-too-human principle.

For the Melanesians who live on the remote Nissan Atoll in Papua New Guinea, laughing at other peoples pain is known as Banbanam. At its most extreme, it involves taunting a dead rival by exhuming their corpse and scattering the remains around the village. More of an everyday sort of Banbanam is gloating at someones humiliating failure behind their backas when the rival villagers feast day is rained on because their Weather Magicians spells fail, or a wife grabs her cheating husband by the testicles and ignores his pleas for mercy. Banbanam is a kind of resistance too. Melanesians still enjoy telling the story of how an Australian government minister visited the village, got annoyed because the villagers wouldnt do what he wanted, drove away in a huff and crashed into a tree.

In historical portraits, people beaming with joy look very different to those slyly gloating over anothers bad luck. However, in a laboratory in Wrzburg in Germany in 2015, thirty-two football fans agreed to have electromyography pads attached to their faces, which would measure their smiles and frowns while watching TV clips of successful and unsuccessful football penalties by the German team, and by their archrivals, the Dutch. The psychologists found that when the Dutch missed a goal, the German fans smiles appeared more quickly and were broader than when the German team scored a goal themselves. The smiles of Schadenfreude and joy are indistinguishable except in one crucial respect: we smile more with the failures of our enemies than at our own success.

Make no mistake. Over time, and in many different places, when it comes to making ourselves happy, we humans have long relied on the humiliations and failures of other people.

There has never really been a word for these grubby delights in English. In the 1500s, someone attempted to introduce epicaricacy from the ancient Greek, but it didnt catch on. In 1640, the philosopher Thomas Hobbes wrote a list of human passions, and concluded it with a handful of obscure feelings which want names. From what passion proceedeth it, he asked, that men take pleasure to behold from the shore the danger of them that are at sea in a tempest? What strange combination of joy and pity, he wrote, makes people content to be spectators of the misery of their friends? Hobbess mysterious and terrible passion remained without a name, in the English language at least. In 1926, a journalist in