My Apprenticeship in the Gardens of Kyoto

Leslie Buck

Timber Press

Portland, Oregon

For my first mothers:

Anne Buck

Dorothy Whittaker

Betty McGrew

Contents

Preface

I am the person you spot up in the tree, dirt smeared across my face. Is that a large bird up there? you may wonder. My pruning shears busily clip away as I try to bring out the natural beauty in the tree in my playful, sometimes assertive, sometimes delicate way. The tree, shears, and I are dancing partners under the sun. Weve been together for decades.

Passersby might step right over my pile, despite the rake I have lain across the sidewalk as a deterrent. Sometimes, without asking, theyll pick up a branch for their dog and walk on, hoping not to bother me. Or maybe Ill catch their eye as they walk right under a branch Im sawing that is about to drop. People are curious about a female pruner high up in the tree, wielding sharp tools. Just as I covet the stylish outfits worn by the women who walk beneath my tree, I believe others want to be like a kid again, up in the tree with me.

This kind of interaction would never take place in Japan, where, starting late in the year 1999, I worked for three long seasons, watching the gardens explode with summer growth, morph overnight into radiant fall colors, and molt their leaves after the first bitter cold days of winter. Owing to their devotion and skills, traditional gardeners are treated like brain surgeons by the Japanese public. Clients and people walking by give them plenty of space, never talking to them unless summoned, so as not to break their concentration or pace. When addressing a gardener in Japan, people first apologize for interrupting, and then speak in reverent tones to the craftsman they know has trained like a star athlete, with much physical effort and years of sacrifice, in order to create over centuries some of the most beautiful gardens in the world.

But I dont mind if someone asks me a question while Im up in a tree. Im naturally friendly, having been born in the heart of the Midwest and raised from a young age in a sleepy California beach town. At the age of nearly thirty-five I went to Japan in pursuit of a gardening apprenticeship. I had to ask permission in person to join the company, to show I was serious, the way others have approached landscaping companies for centuries.

I didnt always feel daring. Im an unusual adventurer: more worried than eager, unable to pick up new languages easily, and often getting lost. Im willing to challenge myself, but my emotions, both anxiety and joy, always play a large role. Still I never let any flaws in my character keep me from going after a dream. My struggles were a gift. They taught me determination, and sometimes humor. In Kyoto I learned to work in silence, to run fast between projects, and to take breaks three times a day, with green tea and snacks. I grew to appreciate how hard I tried rather than how much I succeeded. I discovered a way to feel proud even when I came home dirty and exhausted.

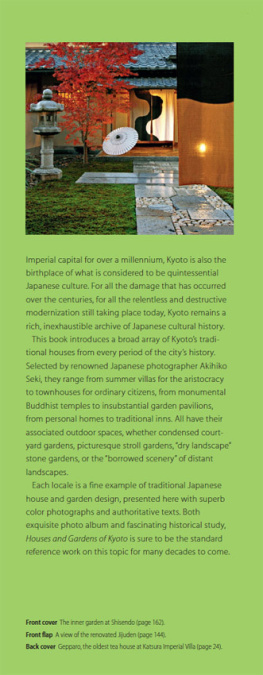

In Kyoto I discovered that 90 percent of the private home gardens of Japan are native; the Kyoto private homes, monasteries, and imperial gardens I worked in were some of the most natural-looking gardens Id ever seen. The miniaturized and overly sheared Japanese gardens Id expected were surprisingly absent. Most of the gardens were designed and pruned to look so sincere that visitors might think theyd stepped into a piece of forest left behind in the city. One of my coworkers, who once fell asleep in a pine tree, said to me, Leslie, tell your friends back home that Japanese gardens are as natural as possible.

I tend to work with serious focus. So I prefer answering inquires when sitting in a garden with a lovely table full of tea and cake nearby. A garden desires to be enjoyed. I love to teach others about my craft, and I enjoy pruning in the garden one day and writing in a caf the next. Spending time in nature allows me to ruminate over my writing and ideas. The gardens inspire me and offer a paid workout. The feminine weeping red pine in one of my sixty-year-old gardens, or the two girls I always see walking by with their two well-fed boxers in San Franciscos Sea Cliff, give me an idea for my next chapter.

When I returned from my Japan apprenticeship, I built up my pruning business so I could buy a home and have access to healthcare, two things every long-term hard worker should be able to afford. I joined volunteer pruning projects at nonprofit gardens with the Merritt College Pruning Club to teach others my craft. I continued to learn from classes, conferences, lectures, sketching, and almost thirty years of hands-on garden work.

The way to become a master craftsman in Japan is to practice ones craft and to teach. One garden craftsman told me that as a hobby he studied ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging. When I asked him how long hed been doing this, he said, Oh, not very long, only fifteen years. Im just an amateur. It requires many years of hands-on experience to fully understand a craft. Japanese craftspeople take their work seriously. I begin my story at one of the first Kyoto gardens I worked in, where the garden craftsmen of Japan began to teach me not only about pride, but about how to find heart in the garden.

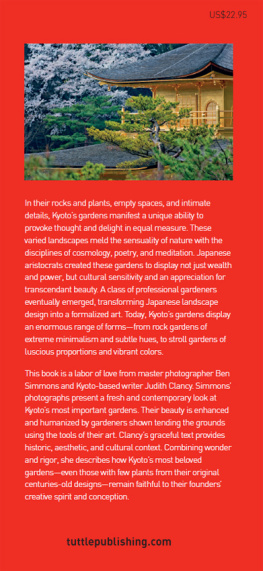

Watchful Turtle Is Given a Pine Test

This garden is not very old, my coworker softly whispered to me. Only three hundred and fifty years. After driving for a while through the streets of Kyoto, we made a sharp left onto an almost hidden drive and entered the garden through a back gate. Our truck became enveloped by a lush woodland landscape. I found out later that, centuries before, the property had belonged to a wealthy Kyoto merchant. A formal restaurant now overlooks the wild, forested scene. Central to the landscape was a wide stream, an ancient canal once used to bring rice and goods on barges into Kyoto.

Two gently sloping embankments rose up from the stream, blanketed in ferns, azaleas, and nandinas in endless overlapping shades of green. Birds called from every direction. Insects buzzed and circled us like young playmates. Even the still turtles seemed to be tracking our movement with their eyes. A few stone lanterns dotted the landscape, but the flowing water held my attention. A building sat atop a hill, where diners watched the activity through large windows.

The youngest worker in our garden crew looked at me with a worried expression as he tentatively handed me a pair of karikomi, Japanese hedge shears with long handles and narrow blades. I wondered if he thought I might throw the tool back. I tried to smile reassuringly as I thanked him softly in Japanese. I later learned that hed been gardening for only seven months. Id been studying horticulture and running a landscape pruning and design business for more than seven years. Nevertheless, he would eventually become my boss. Japanese craftsmens hierarchy is determined by time in the company, not by experience. I had arrived just a few months after the shy teenager had joined our crew. This kind of hierarchy sometimes seems absurd to Westerners, but it produces efficient work teams with no competition between members because positions are set. With the possibility of having ones rank lowered by switching companies, hierarchy ensures that apprentices commit to the company that trains them.

I paid careful attention to the young gardeners energetic technique that day while we worked together on some overgrown azalea hedges. His

Next page