Contents

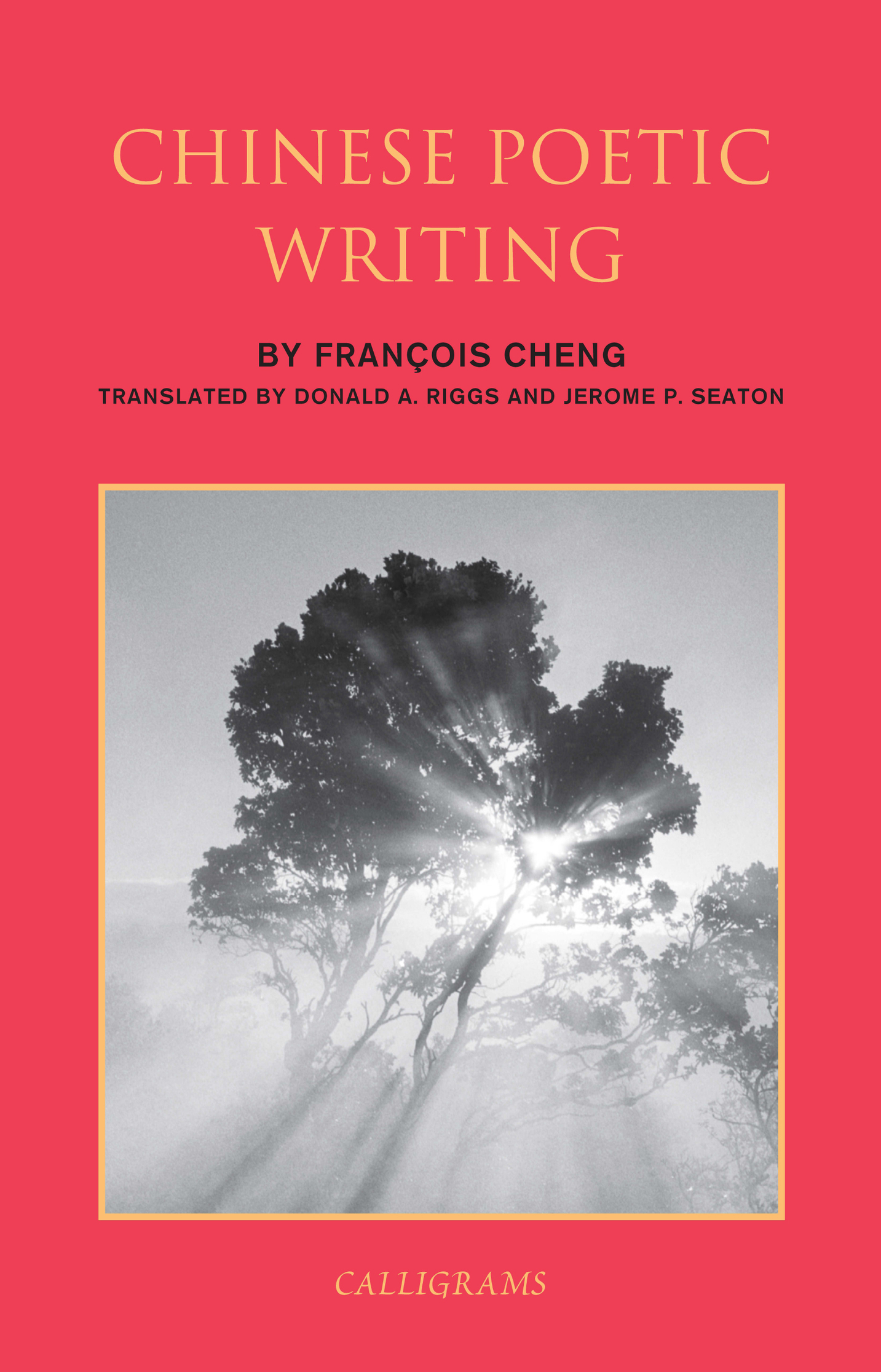

Calligrams

Series editor: Eliot Weinberger

Series designer: Leslie Miller

Chinese Poetic Writing: With an Anthology of Tang Poetry

By Franois Cheng

Translated by Donald A. Riggs and Jerome P. Seaton

Editions du Seuil, 1977, 1982 et 1996

1982 by Indiana University Press. Rights to the Seaton-Riggs English-language translation licensed from the original English-language publisher, Indiana University Press

Expanded edition copyright 2016 by The Chinese University of Hong Kong

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cheng, Franois, 1929- author. | Riggs, Donald Albert translator. | Seaton, Jerome P. translator.

Title: Chinese poetic writing : with an anthology of Tang poetry / by Franois Cheng; translated by Donald A. Riggs and Jerome P. Seaton.

Other titles: criture potique chinoise. English

Description: Expanded edition. | [Hong Kong] : The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press; [New York] : New York Review Books, 2016. | Series: Calligrams | In English; with anthology in English and Chinese. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016018877 | ISBN 9789629966584 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Chinese poetryTang dynasty, 618-907History and criticism. | Chinese poetryTang dynasty, 618-907. | Chinese poetryTang dynasty, 618-907Translations into English.

Classification: LCC PL2321 .C5413 2016 | DDC 895.11/309dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016018877

ISBN9789629966584

Ebook ISBN9789629968984

Published by:

The Chinese University Press

The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Sha Tin, N.T., Hong Kong

www.chineseupress.com

New York Review Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014, U.S.A.

www.nyrb.com

v4.1

a

To the memory of my father

Introduction to the English Language Edition

American sinology is properly celebrated for both its richness and its vitality. Graced with its many studies of the highest quality, the American reader is doubtlessly in the best possible position to be familiar with the overall scope of Chinese poetry and with the works of individual poets. This study, which is semiotic in nature, attempts only to shed some light upon the formal structures of that poetry, in order to help the reader to grasp a few of its implicit aspects which have often been neglected.

On the occasion of the publication of this English language edition, I would like to propose several summary reflections to place Chinese poetic writing in the more all-embracing context of Chinese cosmology, reflections which may, I hope, contribute to the clarification of the fundamental approach which has guided our research.

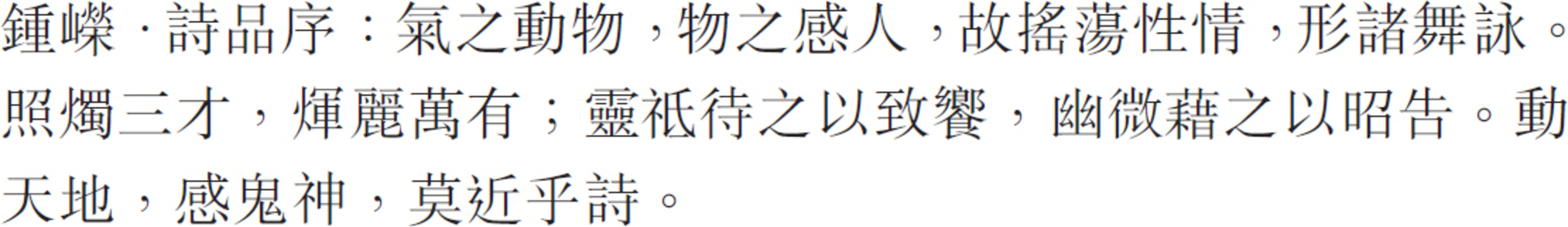

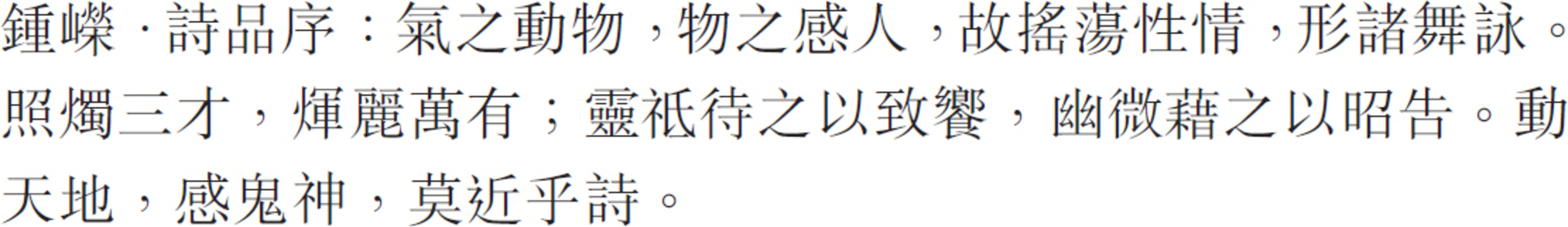

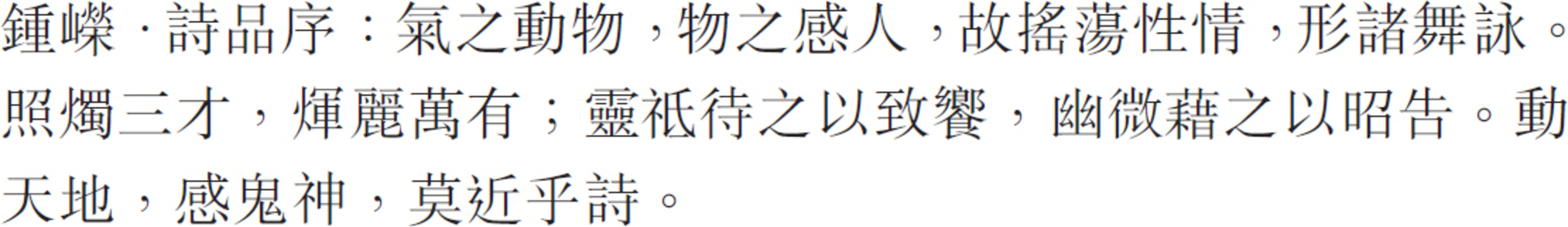

The eminent role which poetry played in China is well known. This eminence is due not only to the important functions, both aesthetic and social, which poetry has always had, but also to a more essential phenomenon: the quasi-sacred veneration devoted to the ideographic writing itself in China. This writing was perceived not as an arbitrary invention of man, but as the result of supernatural revelation. Ancient myths report that on the day when Cang Jie (Tsang Chieh), inspired by divinatory figures, traced the first signs, Heaven and Earth trembled, and gods and demons wept. For, through the magical trickery of the written signs, man would henceforth share in the secrets of Creation. (Chinese thought is, then, as much marked by the myth of Cang Jie, who steals the signs of written language, as is Western thought by the myth of Prometheus, who stole fire.) From this perspective, poetry, which transforms written signs into song (a sung writing), has as its highest function the rejoining of the human spirit to the original and vital forces of the Universe. Let us listen to Zhong Hong, of the sixth century, from the introduction to his Shi Pin: The Breaths animate beings and things; these in their turn inspire man. Pushed by the impulsions and feelings which dwell within him, man expresses himself through dance and song. His song is a light which illuminates the Three Spirits (Man-Earth-Heaven) as well as the ten thousand creatures. Thus, it constitutes an offering to the spirits, and makes manifest the hidden mystery. For upsetting Heaven and Earth, for moving the Gods, nothing equals poetry.

We may understand, then, the link between poetry and cosmology. We will see that the Chinese poetic language, in its structure, embodies the very laws which rule cosmology as it was conceived of in Chinese thought.

This cosmology, contained in seeds in the Yi Jing (I Ching, or Book of Changes), was formulated in a schematic but decisive form by Lao-zi (Lao Tzu), the founder of Taoism. In Chapter 42 of the Dao-de-jing (Tao Te Ching, or Book of the Way and Its Virtue), it is written:

The Tao of Origin gives birth to the One

The One gives birth to the Two

The Two gives birth to the Three

The Three produces the Ten Thousand Things

The Ten Thousand Things take Yin upon their backs

And draw Yang unto their bosoms

Harmony is born in the Void, from the Median Breath

With great simplification we can make the following commentary: The Tao of Origin is conceived of as the Supreme Void (

) from which emanates the One, which is none other than the primordial Breath (

) from which emanates the One, which is none other than the primordial Breath (