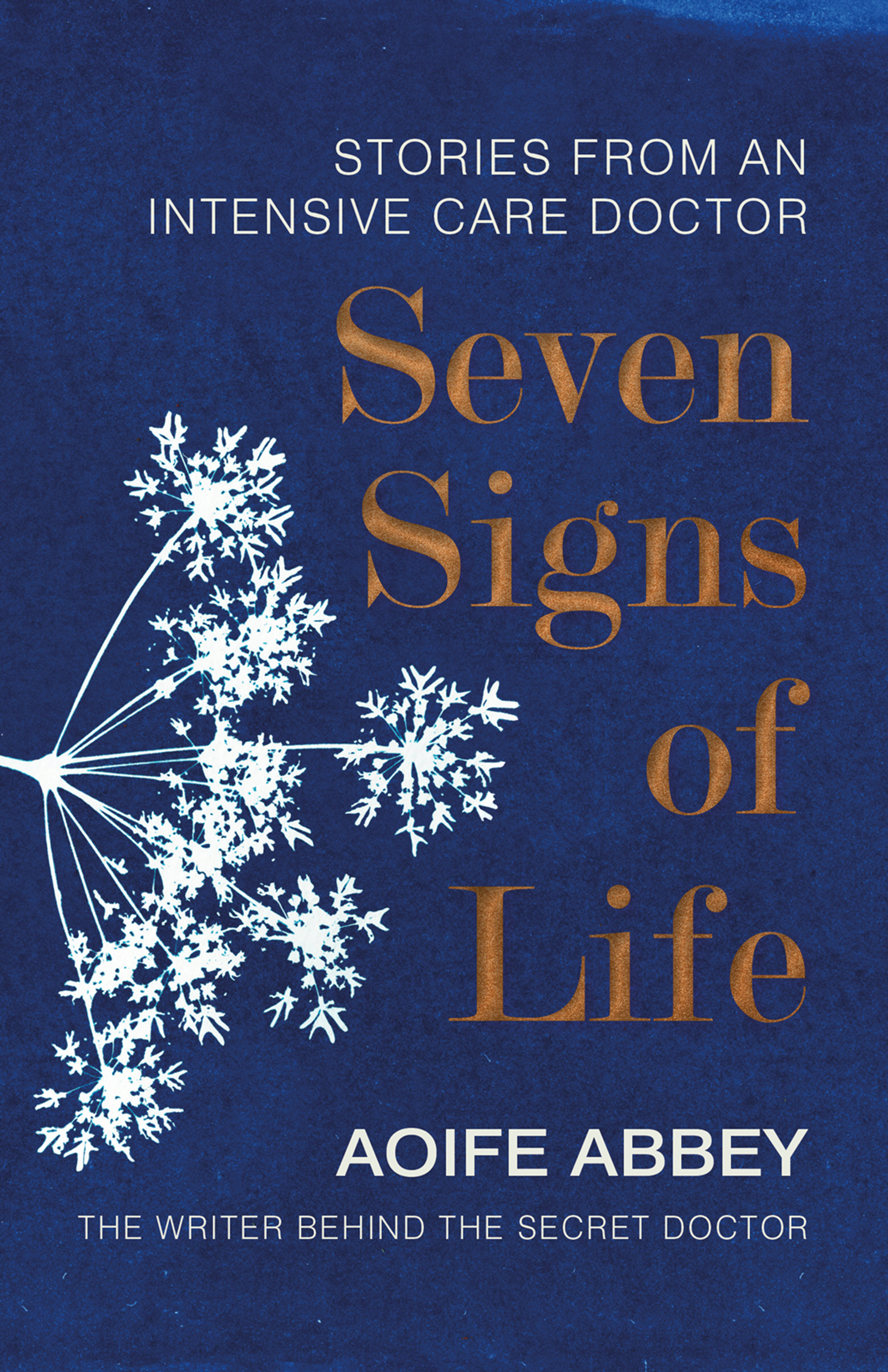

AOIFE ABBEY

Seven Signs of Life

Stories from an Intensive Care Doctor

Contents

About the Author

Aoife Abbey grew up in Dublin, Ireland. She completed an undergraduate degree in Biological Sciences at the University of Edinburgh, before graduating in 2011 from medical school at Warwick University. She is a member of the Royal College of Physicians, Fellow of the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and council member at The Intensive Care Society UK. From September 2016, Aoife wrote a blog under the guise of the British Medical Associations The Secret Doctor. This is her first book.

To my big brother Aaron, an activist. We miss you. And to those who have trusted me, often without choice.

IX. The Four Ages of Man

He with body waged a fight,

But body won; it walks upright.

Then he struggled with the heart;

Innocence and peace depart.

Then he struggled with the mind;

His proud heart he left behind.

Now his wars on God begin;

At stroke of midnight God shall win.

W. B. Yeats, Supernatural Songs

Authors Note

The events described in this book are based on the authors own experiences and they have been collected over a period of years, from at least ten different hospitals or healthcare practice settings. While all of the events described are memories of real-world events, the names of patients, relatives, associates and colleagues, if used at all, have been deliberately changed. Additionally, personal and identifying details have been changed. This includes ages, genders, occupations, nationalities, appearances, familial relationships, medical histories and diagnoses. Any resemblances to persons living or dead that has occurred as a result of these changes will have occurred by coincidence.

Introduction

There are thousands of doctors who, like me, spend their time walking in and out of a countless number of patients lives. I have stood in rooms, stood in corners, sat on beds, sat on chairs and knelt on floors. I have been the visitor who was there when you found yourself most vulnerable, when you lay on a hospital bed or on a trolley in the emergency department. I have put my hands on you, and yet I have been somebody you may never even have known was there at all.

I am a specialist registrar in intensive care and I work on a national training programme for doctors who have finished medical school, worked through a further four years of postgraduate training and are now progressing towards the role of consultant intensivist. As a doctor in a training programme, I am constantly moving jobs and hospitals so far, I have had eighteen separate jobs across seven years.

I dont think I have ever considered myself a writer, though I have always loved to read. I devoured other peoples stories, but it was not until I had qualified as a doctor that I realised I might have some stories of my own. It is the human condition, I think, to try and make sense of things. There has never been a doctor who left medical school fully formed, and perhaps it was because I was so aware of all I had to learn that I started to write. Even seven years on from graduation, the more time I spend in intensive care, the more there is to make sense of. Seven years is a drop in the ocean.

It was more than two years ago that I took up the mantle as the British Medical Associations Secret Doctor an anonymous doctor whose task it was to write about everyday life at work. The Secret Doctor wasnt created to spy on people, whisper truths or blow any whistles. It was mostly created to start a conversation, as a way of suggesting to doctors that there were things we should perhaps talk about more. The intention was to bring together doctors at all points of their career, and the anonymity incumbent in that role was always about focusing the conversation not on the writer, but on the topic at hand. The vision was less about creating a celebrity doctor and more about building a community that could celebrate and discuss, with appropriate honesty, what it is to be a doctor. At least that was the sort of role I had in mind.

Fulfilling this remit meant being honest: about what I knew, and what I didnt. It meant inviting opinions on my own experiences and problems, and it meant writing in a way that lent itself to readers, not just from a healthcare-profession background, but from the public, too. It meant wanting other people to join in.

It also involved thinking a lot about how I felt.

When I took the time to stop and really scrutinise how my job made me feel, I realised the incredible scope of things that I had simply got used to. I realised how strange all the things I had been conditioned to take in my stride might seem to someone who has never walked in my shoes.

I am not talking solely about the advancement of medicine and technology, though I am surrounded daily by the complex equipment we have created in a bid to scupper illness and disease. Instead I am talking about the large part of my job that is reliant not on being able to work with instruments, numbers, drugs and machines, but on being able to work with being human.

Of course ongoing academic achievement and the acquisition of hard skills are paramount to a doctors development, but they are not the whole story. Many of the pivotal moments in any doctors story are about learning how to talk to people, to understand them and to make yourself understood. Competence is not simply about knowing what is possible, but also about understanding what is right. It is about feeling and, more importantly, about knowing what to do with a feeling.

Within the context of what I do in intensive care, you will see that many of my patients are often not just vulnerable, but also temporarily dwelling in another place: sedated and mechanically ventilated. I look after people who are at the extreme fringes of existence, and intensive care can be a realm rendered both inaccessible and strange. When I speak to patients or their families and I feel that a conversation hasnt gone well, sometimes it seems this is because of the power imbalance that my job creates. There can be a sense that I know, or have access to, an understanding about things that give me the upper hand.

I often think relatives might feel the sting in this because I am the one with the apparent knowledge the passport to this world that has taken possession of their loved one. Yet they are the ones who feel it is their job above all to advocate the life of that person they have come to support. They are the ones who are often stuck: frightened, angry, grieving; feeling as if they are waiting to lose everything, or something close to it. It doesnt seem fair that we cannot, at the very least, set off on an equal footing.

The particular point that I want to share with you about the field of medicine I am training in is this: that for all the expensive equipment, all the technology, the screens, the drugs, the lines and the numbers, much of what my world is centred around are feelings that you are already deeply familiar with.

In biology class, you might have learned about the seven characteristics of living things. These are the signs that tell you that a mouse is alive, but that a stone on the beach is not. All of the things that we call living share, at the most basic level, this collection of traits: movement, respiration, sensitivity to their surroundings, growth, reproduction, processes of excretion and the utilisation of nutrition.

Next page