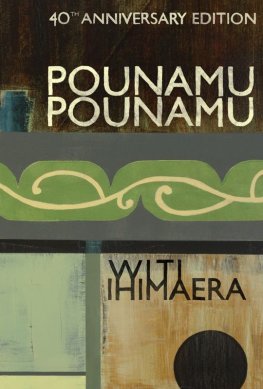

BWB Texts offer a new form of reading for New Zealanders.

Commissioned as short digital-only works, BWB Texts unlock diverse stories, insights and analysis from the best of our past, present and future New Zealand writing.

The team behind BWB Texts : at BWB, Tom Rennie and Bridget Williams; commissioning editors: Geoff Walker and Max Rashbrooke.

Visit www.bwb.co.nz for more information on BWB Texts - including Texts by Sir Paul Callaghan, Rebecca Macfie, Kathleen Jones, Hamish Campbell and Sir Tipene O'Regan.

BWB Texts is made possible by funding support from the BWB Publishing Trust.

Creeks and Kitchens

I use a number of commonplace metaphors about the writing of stories the stream one follows, with a new world opening up at every turning; the ship that makes a voyage of discovery; the mountain one climbs, with great pain, to see the wonderful view from the top; the hole one digs to find the treasure buried deep in the ground. These reveal the central truth, that what stories do is discover and uncover, but what I like most about them is that they are active, even dynamic. They underline what all writers know: storytelling is an energetic trade, even though one sits in a chair all day, putting words on a page.

Ive also got a couple of words, common words, but far from commonplace, that have a special potency because of where they come from. Im sure we all have these, from deep in our past, from our childhood. These words are almost always nouns. Theres a kind of magic in naming. When humans developed speech and fitted a particular sound to a physical thing it must have been an action of great power the bringing of objects under the control of the mind. It can still be like that and I think poets know it better than prose writers. The simple naming of things in poems can be hugely powerful tree, rock, hand, eye. When properly used these become the first tree, the first rock, the only hand, the only eye. And then, of course, these nouns can take on all sorts of private associations and for the individual become hugely suggestive, so that a word that makes one person cry will make another laugh.

My special nouns are creek and kitchen. Two very ordinary words but for me they are the most suggestive in the language and at certain times, when Im properly receptive, they can start me on all sorts of journeys. Creek and kitchen are the poles that I moved between for most of my childhood.

I grew up west of Auckland, in Henderson, which is a suburb now, part of the great Auckland sprawl. But in the 1930s and '40s it was a country town, cut off by farms from the city. There was a railway station, a boarding house, a blacksmith shop, a grocer, a butcher, a baker, and not much more. Four churches, a little brick jam factory, lots of orchards, Corbans winery, and some smaller Dalmatian ones, producing mostly sherry and port, which was sold, after 1941, to US servicemen who came out west in Jeeps. That was Henderson.

But, most importantly for me, it had a creek, and on that creek I seem to have spent most of my boyhood. Today, if I close my eyes, I can recreate it pool by pool for a couple of miles of its length. It was one of those slow-moving deep-green creeks with bottomless pools. I never dived deep and when I swam across I went fast, frightened of what might be lurking down on the bottom. We fished for eels, we sailed tin canoes, we explored.

Henderson Creek began at the dam and ended at Falls Park. We walked on its ferny banks, red mats of willow root elastic under our feet. A naked man washed himself in a pool. His eyes did not blink. My mother turned us back, we felt her fear and asked over and over, Why Mum, why are we going? We knew there was something we had not understood.

That was up by the dam. The dam was half a dozen logs held together with rusty spikes. A tumble-down shed stood at the far side, with an iron wheel bedded in concrete. Someone had once made heel and toe plates there. It was a spooky place. Huge eels lived in pools on its lower side. On the far bank was a pit we could not see the bottom of. The man was a part of the place. He had black eyebrows and a black unshaven chin. My mother said perhaps he was a swagger. We knew what swaggers were. She had written a story about one. He had eaten scones in the kitchen, butter ran down his chin. He threatened the cook (our mother) and Jim the foreman punched him on the jaw.

So the creek was for games and adventure, but it was also the dangerous place, where people might even die.

But then I could run home, up past the swamp, through the abandoned orchard, past the draught horses in their paddock, along our street, and come to that other place, kitchen. And there was Mum lifting the lid of the pot to stir the stew, feeding another piece of tea tree into the stove, turning Dads work socks on the drying rack and that was the safe place, that was where harm could never come.

When someone says the word kitchen I get an instant flash of that room, with its black stove and drying rack, its brown lino, its worn mat and wooden table, the Philco radio on the mantelpiece. And creek works in a similar way. These are things that can start me writing, they have memory attached to them and, in a more shadowy way, values and meanings. Theyre part of an emotional and moral universe, theyre stopping places and theyre starting places. They underline for me the essential duality that every writer must know: familiarity/mystery, safety/danger, dark/light, good/evil. So here are two words, bits of language that, for me, are enormously powerful and suggestive.

Now I mentioned my mother stirring the stew, but please dont think kitchen tasks were all that she could do. I can remember getting out of bed late at night and creeping out to the kitchen and finding her sitting in a chair with her feet in the oven to get the last warmth from the stove, writing a poem or story in an exercise book. It wouldnt surprise me to learn that hundreds of New Zealand women behaved like that, after their husbands and children had gone to bed.

Over the road from the dam was Peacehaven, our grandparents house. We were told not to ask for anything to eat, but we asked and our grandmother had a biscuit or a piece of bread and jam for us. My mother visited her every day while we ran in the orchard and played in the summer house. We set mousetraps for sparrows and caught the one my grandfather had trained to take crumbs from his hand. He made us collect stamps for him as a punishment.

My grandfather was deaf. He had an ear trumpet that now and then we were allowed to shout into. We did not see him often. He spent his time in his study where there were shelves of books that went up to the ceiling and a brass Buddha that smoked thin sticks of incense.

In the afternoon we walked home along Millbrook Road. The creek was on our left. There was the swimming-hole where I learned to swim. A beautiful grown-up girl dived off the over-hanging willow branch and came up shouting, Who said you cant touch the damn bottom? Mum, I thought you said ladies dont swear. Well dear, she isnt a lady.

We passed my uncles orchard. He had been a sailor, he painted pictures, and we knew there was something Wrong about his marriage. He was a happy man, always laughing, but his wife was not happy. She had chased him through the orchard with an axe.

We came to our street Newington Road. At the end of it lived the Yelaviches. (Our neighbours names delighted us Green-nose, Pink-knee, Yellow-vitch.) On the corner was the house of our friend Murray whose father drank poison in the bathroom.