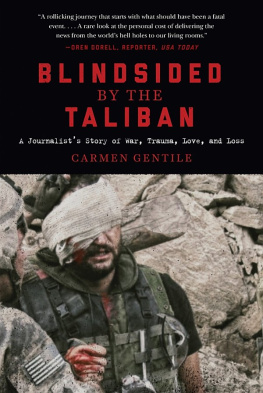

Copyright 2018 by Carmen Gentile.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Michael Wilson

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2968-1

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2970-4

Printed in the United States of America

For James Foley, Matthew Power,

and all the freelancers who werent as lucky as I was.

And for all the soldiers that have ever served at Combat Outpost Pirtle King.

A portion of sales of Blindsided by the Taliban will go to RISC, Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues. RISC teaches life-saving first aid techniques to freelance journalists working in conflict zones.

To learn more about RISC, go to www.risctraining.org.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

A friend from Afghanistan was busting my balls when he said my greatest career achievement is getting shot in the face.

I might be irked by his besmirching of the entirety of my journalistic accomplishments if he wasnt sort of right.

Sure, Ive reported from dozens of countries spanning the globe, but not to great acclaim. Ive never won any of the myriad awards, grants, and residencies regularly doled out to my deserving peers. In fact, Im willing to bet few of my colleagues have ever even heard of me.

For nearly two decades Ive flown under the radar, embarking on ill-conceived adventures, writing about them, and wriggling my way out of frequent personal mishaps.

Its been, for the most part, a hell of a way to make a living.

But when I got hurt something changed, both in my outward persona and inside me. Rather than being completely unknown, I became that guy who got shot in the face in Afghanistan you know, the one with the girls name what is it again?

I made jokes about my injury when anyone would ask me to recall what happened. Ive always had a penchant for dark humor, particularly as it pertains to my own predicaments. There shouldve been nothing left of me, Id say, wrapping up my umpteenth retelling of that day in Afghanistan with a wicked grin that let mouth-agape listeners know it was OK to laugh about it, too.

But I wasnt OK. I was angry, jittery all the time, and prone to sleeplessness. When I could rest, I had nightmares about being killed in every way imaginable.

When therapy and ill-conceived romantic interludes failed to ease my woes, I decided writing about what happened might help.

It didnt.

Instead, I discovered that unpacking and reexamining the worst period in my life merely amped up my cantankerousness. Even recalling the lighter moments following my injury offered no relief. Meanwhile, I drifted away from most family, friends, and loved ones with little or no explanation.

Perhaps this book offers one.

A little background on how I went about writing this book may also explain, albeit not excuse, my behavior:

I started writing Blindsided by the Taliban in a dilapidated cabin in Pennsylvanian Appalachia I rented during the coldest winter I can remember. In that house with its faulty furnace, rotten floorboards, and a sunken, back-aching mattress, I began cobbling together my story. I poured over hundreds of the hand-scribbled notes on napkins, assorted scraps of paper, notebooks, and my previous reporting trying to piece it all together into something resembling a coherent narrative.

After several months of writing in near-total isolation at my frosty mountain abode, the weather finally broke. I packed up my partial manuscript and notes and rode my motorcycle more than a thousand miles south to Miami. There I had a friend who said I could work at her house while she was vacationing, as long as I fed her two dogs and gave the sickly one a daily shot of insulin. Despite my extreme needle phobia, I agreed to the arrangement, injecting her poor pooch in the neck every morning before going about my business.

The change of scenery and warm weather helped me maintain my momentum, so much so that when my friend returned from her vacation I headed a little further south to a small place in the Florida Keys, where I was my most productive during the course of writing this book. But even in the tranquil, lazy Florida Keys I couldnt find peace.

By now you may be wondering how I managed to afford all this continental gallivanting, considering I hadnt done any paid work for months and freelance journalists are notoriously cash-strapped.

The answer, Im loathe to admit, is lawyers. After years of legal wrangling with CBS over the workmans compensation they owed me from my injury, I finally received a modest settlement that allowed me to take some time off.

Amid that prolonged legal struggle, Id imagined getting a nice stack of cash would surely make me feel better.

Again, it didnt.

Also, the settlement from CBS wasnt enough to sustain me until I completed the book. So, after a year away from the reporting game, I decided to go back to my first love and see if I could jump-start my near-dead career. In doing so, I moved to Istanbul, a popular home base for journalists covering conflict and strife. While there, my book remained my first priorityI did just enough journalism to pay the bills and remind editors I hadnt, in fact, fallen off the face of the earth during my hiatus.

I spent two years editing and polishing my manuscript and submitting it to hundreds of agents and editors, all of which said, No thanks. I worried that my story may never see the light of day and became as despondent as when I first got hurt.

When Id take a break from anguishing over my book to report from the Turkish/Syrian border or Iraq, I was reminded what real suffering was, something Id inexcusably forgotten amid my obsession with my own story. The concerns of a would-be memoirist/reporter trying to find a home for his book were inconsequential compared to those who lost family, friends, and homes amid the wars. When I returned to the comfort and safety of my own home, I felt even worse than I already had for my ridiculous self-indulgence.

Only after my daughter was born did my injury angst finally subside. The demands of a newborn baby and her vulnerability were the kick in the ass I needed to pull myself out of my postTaliban attack malaise.

And as a result, getting shot in the face is no longer my greatest achievement, professional or otherwise.

Knocking up my wife is now firmly atop the list, though my one-in-a-trillion injury has a tight grip on the number two slot for now.

AUTHORS NOTE

In a not-so-subtle homage to my beloved profession of journalism, and because Im used to writing this way, each chapter of Blindsided by the Taliban has a title followed by a date and location. Datelines, as we call them in the reporter biz.

Next page