Woodhall Press, 81 Old Saugatuck Road, Norwalk, CT 06855

WoodhallPress.com

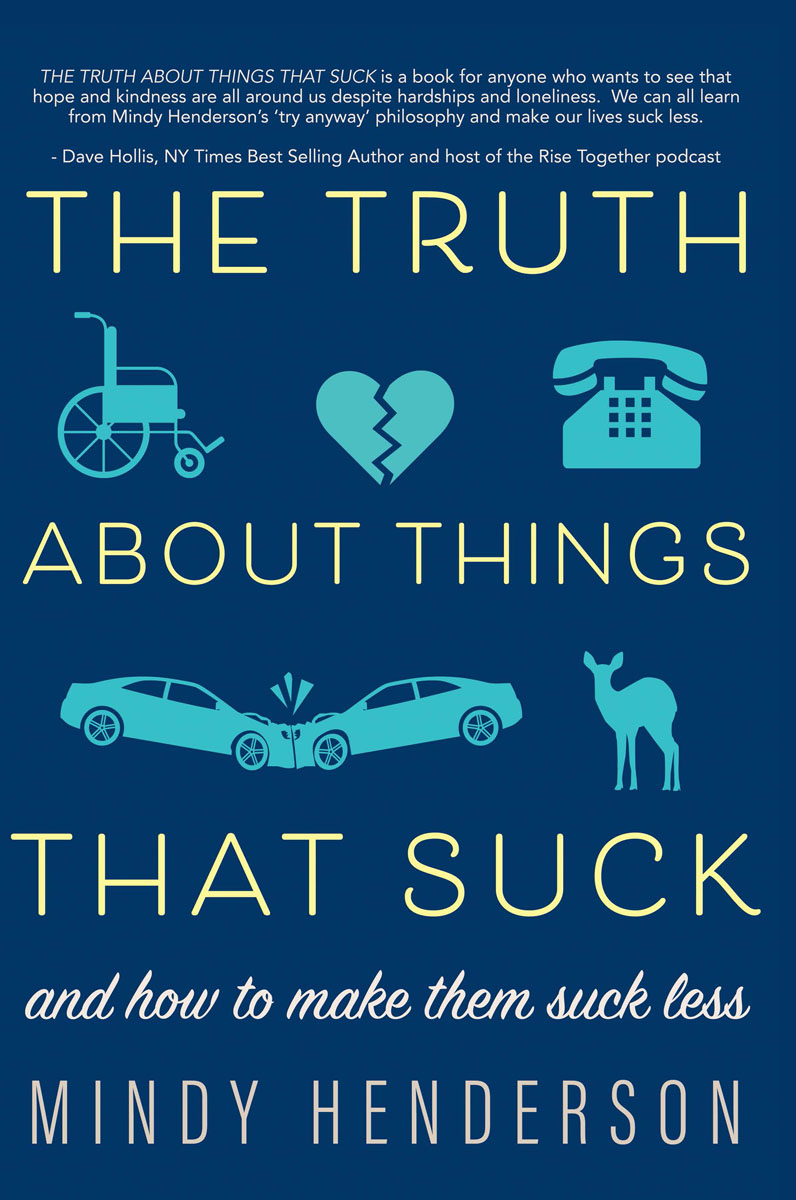

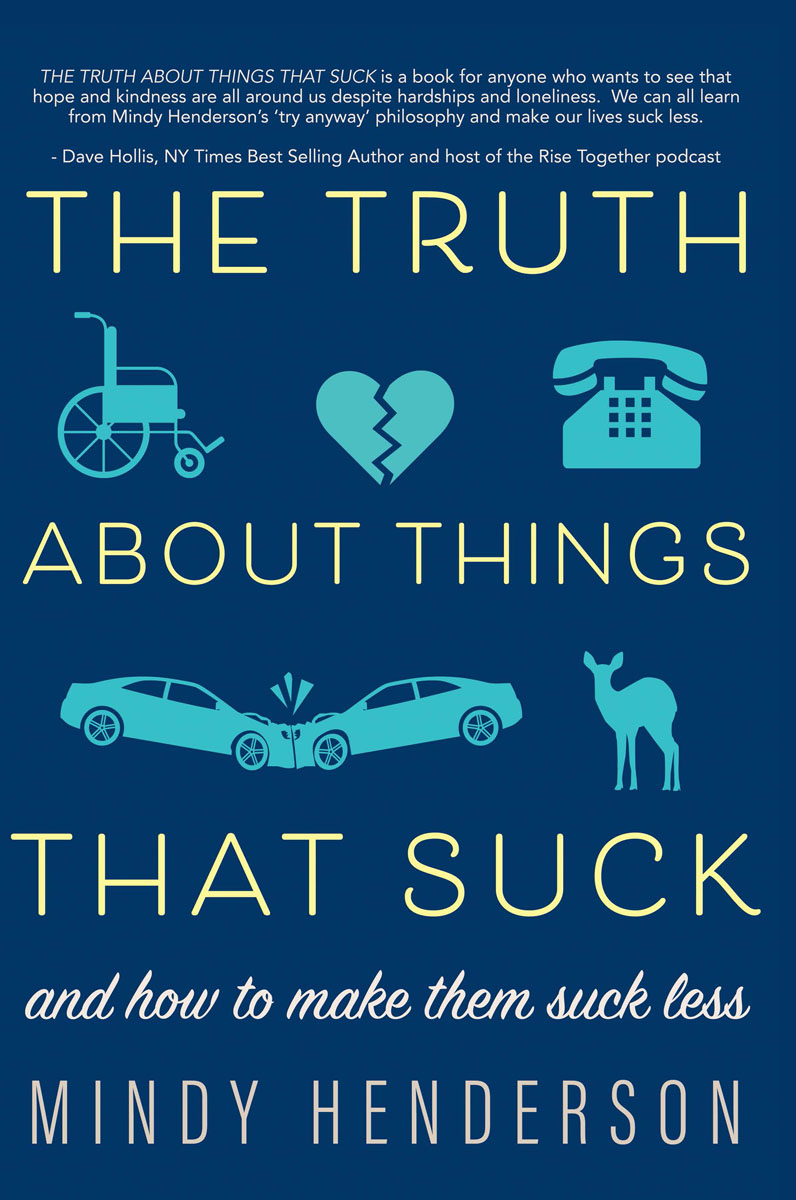

Copyright 2022 Mindy Henderson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages for review.

Cover design: Jessica Dionne Wright

Layout artist: Amie McCracken

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-954907-07-2(paper: alk paper)

ISBN 978-1-954907-08-9(electronic)

First Edition

Distributed by Independent Publishers Group

(800) 888-4741

Printed in the United States of America

This is a work of creative nonfiction. All of the events in this memoir are true to the best of the authors memory. Some names and identifying features have been changed to protect the identity of certain parties. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. The author in no way represents any company, corporation, or brand, mentioned herein. The views expressed in this memoir are solely those of the author.

For mom and dad.

My original source of hope, strength, humor and ambition.

Table of Contents

Introduction:

The Struggle is Real

I used to think that because I was in a wheelchair, my quota of bad luck or challenges and struggles had been met. I thought I couldnt get cancer, lose a job, break a bone, have an accident, or have my heart broken. I actually remember thinking those thoughtsno kidding. I was four-ish, I think, was in my bedroom, and I remember hearing someone else was sick. And I thought to myself, I could never get (whatever the thing was)Im in a wheelchair. Nothing else bad can happen. Ah, the innocence of youth, right? While it was a precious theory, it turned out to be one of the few times in my life when I was wrong (for realask my husband. Im, like, never wrong.). Turns out, there actually were (and still could beoy) plenty of things that could go wrong, hurt me, devastate me, or could traumatize me and show up on any old Tuesday merely to be a pain in the ass.

My disability is what I would label as my primary adversitymy #1 challenge, struggle, and pain-in-the-ass Tuesday. I was diagnosed with a neuromuscular condition called Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) when I was only about 15 months old. This is a condition that (in my incredibly simple, unscientific brains way of explaining) affects my motor neurons ability to function and to send messages to the muscles telling them what to do. Because of the lack of communication to the muscles, they atrophy over time. Just about every muscle in my body is affected. Its a progressive condition, which means, the sucker gets worse over time. As it gets worse, Ive had to grieve the loss of the function I used to haveto be able to reach up to do my own hair, my makeup, to lift a glass up off a table, and drink from it without a straw. The list goes on. I have had corrective surgery for severe scoliosis from my weakened back and trunk muscles, but I still sit a little crooked. There is the potential for pulmonary and respiratory complications, and as a result, my lung capacity is diminished, so things like flu or COVID could be quite serious for me.

There is a bit of a silver lining to my conditionthere are varying degrees of severity and no one case is quite like another. For you brainiacs in the crowd, it boils down to the number of copies of the SMN2 gene you have. I have three copies of it, and the more copies you have, the better off you are. Before you ask, yes, Ive definitely thanked my parents for all the SMN2. It has served me well, and Ive always been on the healthier end of the SMA spectrum.

When I was born, all was wellI was a normal, healthy, happy baby girl. I hit all of the major milestones babies hitrolling, crawling, standing, walking, and talking. But then, I stopped walking and standing (continued talking like a maniacin fact, I dont mean to brag, but my first word was a sentence. My dad came in to get me up from a nap and I looked up and said, Hi daddy. I know, genius, right?).

As for walking, Im told it was almost as if Id lost interest and couldnt be bothered to stand or walk anymore, and there were a few other signs indicating something might be wrong, so my mom took me to the pediatrician, who said I was fine and that it was likely a phase I was going through, and to let it play out.

My parents knew better. Parents know when something is wrong with their children, and their instincts were kicking in. My dad was working in a hospital and was able to get someone else to see us, and that was the first stop on the scavenger hunt it took to get my diagnosis.

Ultimately, I was diagnosed by the head of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. This was 1975 (ugh, okay, Im taking one for the team and giving you the tools to calculate my age!) and there was far less known about my condition back then. As a result, my parents (who by the way, were only in their twenties when this happened and they found themselves with a sick child, having to navigate a complicated medical system to get answers) were told some really scary thingsI would lose my cognitive function. I would not live to be three. While there was no cure and no treatments to speak of, the diagnosing doctor DID agree with my parents who speculated that maybe physical therapy could help. So, they tried. They wanted to know that if I were to leave this world earlier than theyd expected, that they had done everything humanly possible to help me.

I started to get strongerit was slow, and subtle, but the improvements were irrefutable. And then I had a third birthday, and a fourth. And many more after that. AND, I am sitting here writing these wordscognition fully intact. (Although, most mornings that little miracle requires a lot of coffee) The sentence of life in a wheelchair was real, however, no probation, no parole, no early-release for good behavior (and Ive tried SO hard to be good, yall!). So, life in a wheelchair, it shall be.

Here is the thing, though. This story is not one I remember living, of courseits one of those stories that you just always know your entire life. I dont remember who told it to me first, but Ive always had the knowledge of how this all went down. And because of that, my parents became my first examples of having hope in the face of what the absolute experts in their fields were telling them was a hopeless situation. Consequently, hope was one of the first critical concepts to navigating adversity I learned in life.

My parents stood up to the monster in my muscles. They said they would try anyway, and then, they did. There was no guarantee that their efforts would pay off. But they had to believe it could. See, thats the thing about hope. Hope is merely a belief that something is possible.

Sometimes there are ZERO indications that anything else could be, but its about believing anyway. The future is a mystery. Not many of us are able to look ahead and see the future. So, if you cant see it, and cant confirm what is to be, why not believe in the best possible scenario? The worst thing that will happen is that youll be disappointed IF the outcome isnt what youd hoped for. And IF the outcome is a bad one, THEN, absolutely, grieve and feel the pain or the sadness, or whatever is appropriate. But please, dont presuppose pain and suffering. Even if ALL indications, ALL history, ALL the experts, or ALL the facts point to something bad occurring, if you can BELIEVE something else COULD be possible, you hold the power.

Next page