By the Same Author

O My America!: Six Women and Their Second Acts in a New World

Access All Areas: Selected Writings 19902010

The Magnetic North: Notes from the Arctic Circle

Too Close to the Sun: The Audacious Life and Times of Denys Finch Hatton

Cherry: A Life of Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Terra Incognita: Travels in Antarctica

Chile: Travels in a Thin Country

Evia: An Island Apart

Amazonian: The Penguin Book of Womens New Travel Writing

(co-editor)

For children

Dear Daniel: Letters from Antarctica

Copyright 2019 by Sara Wheeler

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Pantheon Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage Publishing, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2019.

Pantheon Books and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Wheeler, Sara, author.

Title: Mud and stars : traveling through Russia with Pushkin, Tolstoy, and Other Geniuses of the Golden Age / Sara Wheeler.

Description: New York : Pantheon Books, 2019. Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019009925. ISBN 9781524748012 (hardcover : alk. paper). ISBN 9781524748029 (ebook).

Subjects: LCSH : Literary landmarksRussia (Federation). Pushkin, Aleksander Sergeyevich, 17991837Homes and haunts. Gogol, Nikolai Vasilyevich, 18091852Homes and haunts. Tolstoy, Lev Nikolayevich, 18281910Homes and haunts. Turgenev, Ivan Sergeyevich, 18181883Homes and haunts. Authors, Russian19th centuryBiography. Russian literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. Russia (Federation)Description and travel.

Classification: LCC PG 2996. W 47 2019 | DDC 891.709/003dc23 | LC record available at lccn.loc.gov/2019009925

Ebook ISBN9781524748029

www.pantheonbooks.com

Cover images: (book) Andy Crawford; (winter landscape) Dovapi; both Getty Images

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

v5.4

ep

In Memoriam

Gillon Reid Aitken

19382016

We sit in the mud, my friend, and reach for the stars.

Turgenev, Fathers and Sons

Contents

Introduction

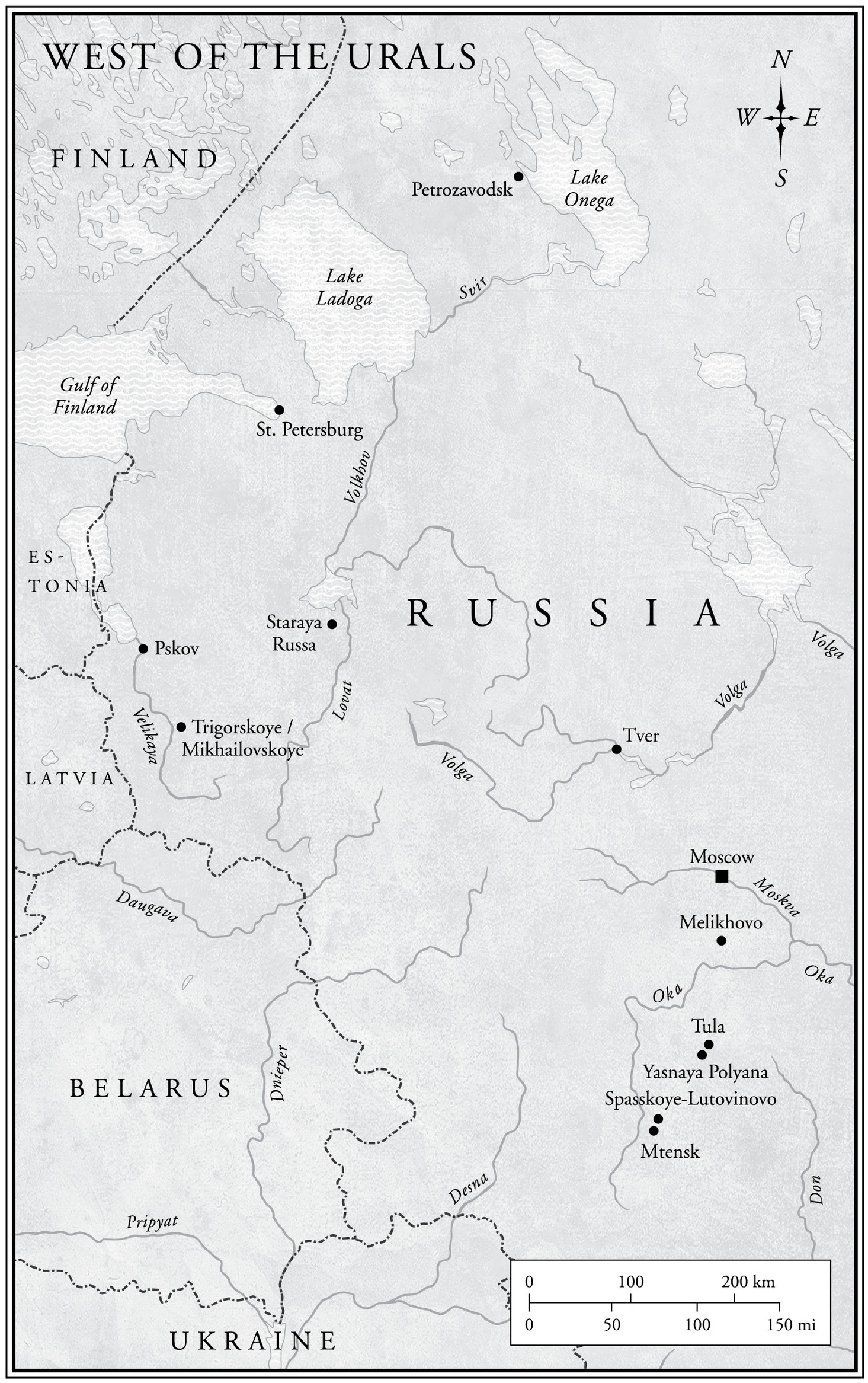

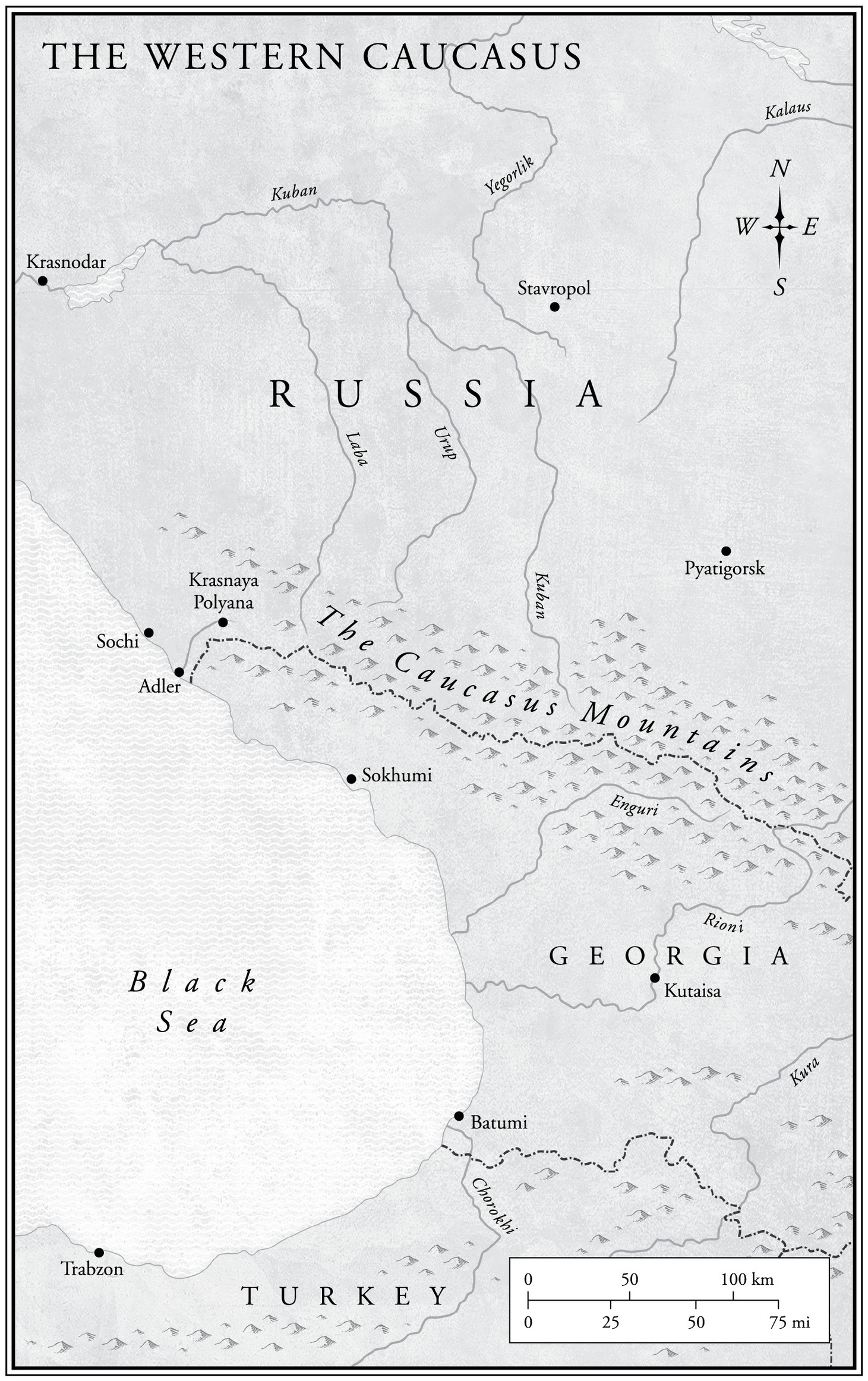

I traveled across eight time zones, from rinsed northwestern beetroot fields to Far Eastern Arctic tundra where Chukchi still hunt walrus in a region the size of France that has no roads. I paddled through the cauldron of ethnic soup that is the Caucasus, where flashing-epauletted Lermontov died in the aromatic air, and where sheaves of corn still stand like soldiers on a blazing afternoon, just like they do in Gogols stories. I sunbathed fully clothed, even wearing a woolly hat, on the shore of fabled Lake Baikal eating caviar with my fingers from a tub purchased at the fish market for 300 rubles (about $4.50). I went to writers homesone of a few things Russia does well (preserving them, I mean). I was at Turgenevs forest-buried estate of Spasskoye-Lutovinovo in spring, when the scent of dog rose hung on the breeze, bougainvillea tubercular on walls. Turgenev complained in a letter that spring in Europe lacked the explosiveness of that season in Russia. I took the Trans-Siberian Railway in winter, crunching across snowy platforms to buy table tennis bats of dried fish from babushki, and sailed the Black Sea in summer where dolphins leapt in front of violet Abkhazian peaks. I was searching for a Russia not in the newsa Russia of common humanity and daily strugglesand my guides were writers of the Golden Age.

Russia was the first foreign country I ever visited. I was eleven. I have been looking over my shoulder at it ever since. Like many, I am in thrall to these writers, roughly Pushkin to Tolstoy, who continue to dominate world literature. It helped, getting through them all, to have spent a lot of time in the polar regions: Tolstoys doorstops were made for whiteouts. I read War and Peace for the first time at the South Pole, looking through the plastic porthole of a tent at hundreds of miles of shimmering flat ice as a thousand horses galloped over the plain at Borodino. The second time, many years later, I was stranded in another tent, on the Greenland ice cap, and again Tolstoys genius filled bright night whiteness. My aim in this book is to show how the best writers of the Golden Age, which I define, broadly, as the period between 1800 and 1910, represent their country, then and now. I followed nineteenth-century footsteps in order to make connections.

The writers here are not a homogeneous group. One scholar says Tolstoy tells us to give away our money; Dostoyevsky tells us to go to church; Chekhov says Im sorry, theres nothing I can do; Gogol says To hell with it. But they all deal with a fumbling search for certainties with which we all engage. And they are failures in one sense or another, as we all are. Tolstoy was obsessed with truth, but only told it in his novels. Dostoyevsky, obsessed not with truth but with God, was a compulsive gambler. He pawned his watch so many times that his saintly second wife said she never knew what time it was. While each chapter of Mud and Stars is centered on a particular writer, or in two cases, a couple of writers, I have aimed at a flowing whole, not discrete essays. There are biographical pagesI always like to know about a writers life, though I am not particularly interested in tracing connections between life and work. Biography has no bearing on a readers appreciation of books. It doesnt matter how much or how little you know about a life.

Moscow and Petersburg are so unrepresentative of Russia that I avoided them as much as possible. They always have been unrepresentative. Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin was born into the nobility in 1799, when French was the language of the cultured classes. Tens of millions of Russians outside the two main cities, however, knew nothing of European influences, just as 140 million today know nothing of oligarchical bling. Their lives were and are consumed with the generally dreadful business of being Russian. I cherish the old-fashioned ideal that government can play a role enhancing the lives of its citizens without threatening civil liberties, allowing individuals the maximum space to live and flourish as they choose. I saw nothing of this in Russia.

Mostly, on my travels, I used homestays. I spent many months in fourth-floor 1950s apartments with windowless bathrooms, sprawled on sofas with my hosts, watching television, my new friends bent over devices moaning about Ukraine. I remember lifting the curtain and peeping from a sofabed in Irkutsk in Siberia at six in the morning to see people scurrying to work through snow in darkness illuminated by the annunciatory glow of the few streetlamps that worked, heads down, shoulders hunched.