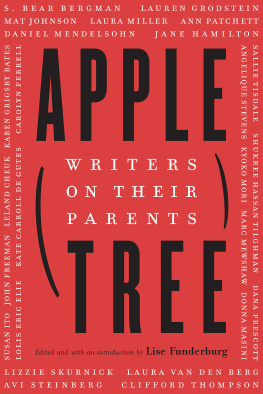

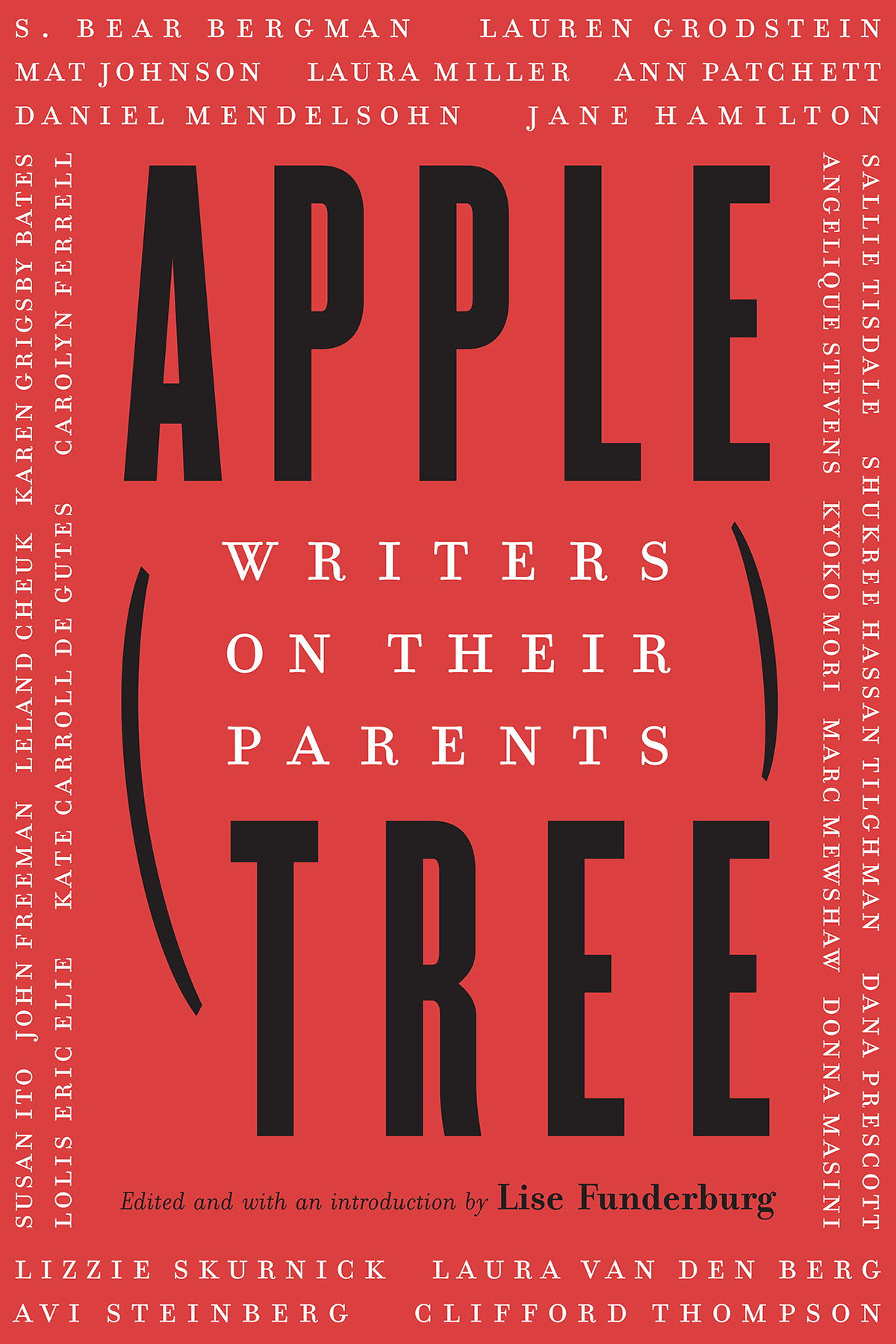

Apple, Tree

Writers on Their Parents

Edited and with an introduction by Lise Funderburg

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln

2019 by Lise Funderburg. Introduction 2019 by Lise Funderburg. Copyright for individual essays remains with the contributors.

Frontispiece: N 127Fruitless, Tanya Marcuse, www.tanyamarcuse.com

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press.

Author photo by Giorgia Fanelli.

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Funderburg, Lise, author.

Title: Apple, tree: writers on their parents / edited and with an introduction by Lise Funderburg.

Other titles: Writers on their parents

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005313

ISBN 9781496212092 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 9781496217219 (epub)

ISBN 9781496217226 (mobi)

ISBN 9781496217233 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH : Authors, AmericanFamily relationships. | Parent and childUnited States. | ParentingPsychological aspectsUnited States. | Identity (Psychology)United States. | Self. | Authors, AmericanBiography.

Classification: LCC PS 129 A 67 2019 | DDC 814/.0093564dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005313.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

To my parents, of course

Contents

Lise Funderburg

Laura van den Berg

Sallie Tisdale

Shukree Hassan Tilghman

Clifford Thompson

Angelique Stevens

Avi Steinberg

Lizzie Skurnick

Dana Prescott

Ann Patchett

Kyoko Mori

Laura Miller

Marc Mewshaw

Daniel Mendelsohn

Donna Masini

Mat Johnson

Susan Ito

Jane Hamilton

Lauren Grodstein

John Freeman

Carolyn Ferrell

Lolis Eric Elie

Kate Carroll de Gutes

Leland Cheuk

S. Bear Bergman

Karen Grigsby Bates

Lise Funderburg

Spring, a few years ago: I dipped into a West Philadelphia coffee shop for something cold and caffeinated. I was on my way to teach, in the hometown Id returned to after decades, and I needed a boost before facing three hours of manuscript scrutiny in an airless basement, the realm of adjuncts who have no pull. The caf was less than a mile from the neighborhood where I had been born and raised: a progressive nest of professors and political activists and inter-something families, where sycamore roots erupted from brick sidewalks and Victorians that had been sectioned into apartments were being reconstituted as single-family homes.

I demolished half of my drink in one swallow and carried the remainder outside. A bright sun snapped me to attention; I tossed the cup into the nearest trash can. The urgency of that actthe automaticity of itcaught me up short, as did the sense of having done something wrong. Look at that, I said to myself, I just broke a rule I didnt know I followed. Having dispatched the iced coffee, I crossed the street, entered my building, and descended its wide marble staircase. Of course, I thought. My actions made perfect sense. Perfect sense for a black man in the 1930s, living in the Jim Crow South. None of which described me.

Summer, 1975 or 1976: I set out from my neighborhood to head for the one where I now teach. Back then, my interests were less academic. I cared about the campus shops that catered to students; the all-concrete swim club with a good cheesesteak place around the corner; boys from school I might run into if I took the right turns along the way. Did I have my teenage uniform on? The T-shirt and Army Navy Store overalls that Id embroidered and patched to within an inch of their life? Was I wearing shoes? Probably, probably, maybe not.

I ambled along, carrying a can of sodaFranks Black Cherry Wishniak or possibly a Dr. Pepper (both upstream flavors in a cola/uncola world). My fathers car pulled up alongside me. He and my mother had split a few years prior; I saw him for weekly visits or when he drove by in his late-model Impala on the way to show a house or put up a For Sale sign. Dads passenger-side window sank down (he had electric). He leaned over to speak. I doubt he bothered with hello.

Should you be drinking like that on the street?

My father didnt make us call him sir when we answered his questions, the way my uncles had raised my cousins to do. Nonetheless, my sisters and I had learned to answer without hesitation and never with slang or ambiguity. Yes or no, none of this yeah or maybe or I dont know. We learned not to hedge the start of a sentence with I think... because that prompted an immediate You didnt think.

But on that hot street and with my guard down, I did the unthinkable. I hesitated. I could not form a response because I did not understand his question. Sodas werent forbidden. It was hot out. Id certainly bought it with my own money. In that sliver of silence where I scrambled to make sense of his words, he dropped the matter. Another aberration.

Ill see ya, he said, and drove off.

My father was born in 1926. He grew up in rural Georgia, where his own father wasnt known as the towns doctor or the towns colored doctor but the towns nigger doctor. Peonage farms and poll taxes were the order of the day, and black people landed on the chain gang for minor and manufactured infractionsclaims of vagrancy, public drunkenness, loitering, or curfew violation. For residents of my fathers neighborhood, Colored Folks Hill, every public action had consequence and every gesture was met with judgment. My grandfather never left the house without a necktie, even to go fishing and even in the bone-melting heat of the Jasper County summers. Why wouldnt my father flinch, some forty years later, when he saw me slurping down a soda on the sidewalk, an unguarded, unmasked teenager with not a care in the world? And I, his childhardwired to win his affection and diffuse his ready angerwhy wouldnt I absorb his admonishment, however irrelevant or confusing?

Most Americans know the adage, The apple doesnt fall far from the tree. Germans have it tooDer Apfel fllt nicht weit vom Stammthough theyre specifically measuring the distance from fruit to trunk. The Spanish version has to do with splintersde tal palo tal astillawhile the French rendition takes an absolutist tone, with Les chiens ne font pas des chats.

In some way or another, most of us come to realize that we are, more or less and for better or worse, chips off the parental block. That fact alone is not what prompted me to commission the essays that fill this book. Instead, I was intrigued by what came after the sidewalk-borne shock of recognition: the curiosity and amusement and compassion and insight, palpable evidence that relationships continue to evolve as we make our way through life, even if one party (in my case, my father) is dead and gone. As the years go by, these discoveries pass through a different filterone thats less reactive, more gentle. We begin to welcome these reflections and refractions, however they come. Unanticipated reckonings result, thanks to the discernment weve gained along the way, tempered as it is by firsthand exposure to birth and death, to faith and betrayal, to endurance and impermanence. What other inheritances, I wondered, could be explored through those flickers of likeness we stumble upon at events large and small: at weddings and wakes, at reunions and after goodbyes, from a gesture, a phrase, a glance?

Next page