During the commissioning and editing process for Syria Speaks: Art and Culture from the Frontline, we kept asking ourselves about the value of art and culture when such untold bloodshed was taking place in Syria. Wouldnt the voices in the anthologys fiction, poems, critical essays, cartoons, digital illustrations, art installations, paintings, photographs and films suffer the same fate as Syria itself, and be obscured or blotted out as the sound of weapons reached a deafening crescendo?

These questions and many others seemed unanswerable at that time, but they were integral to our early motivations in putting together this book. In the end, it was the over fifty contributors to Syria Speaks an impressive array of established and new writers, critics and artists from a cross-section of society who provide an answer. Simply put, creativity is not only a way of surviving the violence, but of challenging it.

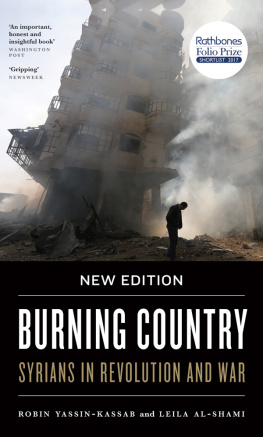

After three long years, many friends and people in the field have fallen into deep depressions and disappointment. Of course, none of them support the regime anymore; but they have lost their ability to back the revolution because it has become so complicated. Those who participated in it have changed, as have its political perspectives. Since the beginning of the uprising in 2011, everything has been radically altered on the ground except for its artistic identity.

Many Syrians had thought their Arab Spring would be different from those in Egypt and Tunisia, and they began constructing a Syrian revolutionary identity through political posters, performances, songs, theatre and videos. Even ordinary people with no experience of the arts started discovering their artistic natures in a country where free expression was often controlled and government regulated. While there are people who do not consider arts activism as an expression of popular culture, for Syrians it was a radical departure from a forty-year-long history of silence. They observed or participated in an outpouring of free expression that even surprised them, and also shocked the countrys custodians of official culture.

The artists, writers, performers and musicians featured in Syria Speaks eschew phrases like conflict and civil war to describe the situation in their country. For them, these words suggest an equal playing field between the aggressor the regime of Bashar al-Assad and the victims, the Syrian people who have been targeted by government violence and brutal sectarianism.

Despite these changes, those who participated creatively in the first year of the revolution continue their efforts; but instead of one enemy, they now face many. They believe that art is a tool of resistance, and that it is integral to social justice emblematic of a life that is shared, not destroyed and that it will protect Syria from the forces of Assad and the extremists in the future.

Syria Speaks opens with a veiled photomontage of the victims of the 1982 Hama uprising. This massacre took place within living memory of the majority of Syrian artists, writers and activists. However, the regime had forced the Syrian people to forget it. After the first phase of the countrys essentially nonviolent revolution in 2011 was met by extreme violence on the part of the regime, Syrian activists and artists started revisiting the events of 1982. The artist Khalil Younes explained: Now when we see what happens to peaceful protestors, we suddenly realise what happened in Hama. Those people lost brothers, sisters, whole lives and nobody did anything about it. The regime has been lying to us for thirty years and those people have been living with their fear and pain for thirty years. When I came to that realisation it was terrible.

Violence past and present cast a long shadow over the country. What started as a peaceful revolution was fully militarised by the summer of 2012, and many of the books contributors have been enmeshed in the conflict. Samar Yazbek, writing a diary of the revolution, travels through northern Syria where the rebel groups have been holding off the regime and uncovers miraculously peaceful scenes of rural life. The artist Sulafa Hijazi explains how dangerous it was to create her digital illustrations in Damascus, each one an unconscious response to the growing darkness enveloping her family and friends as they were each arrested by the regime. The filmmaker Ossama Mohammed contributes a short story, told in cinematic bursts, about a character named after Suad Hosni, the famous Egyptian film star. Suad has been going on government-sponsored demonstration marches since primary school, and is a staunch supporter of the regime until she witnesses her best friend murdered on television during one of the protests. Lettuce Fields, excerpted from the most recent novel by veteran author and screenwriter Khaled Khalifa, deals with approved and unapproved memories, meanings that are never allowed to be spoken of in a totalitarian state. Khalifa describes how living through this labyrinth of lies and fears unhinges a family in Aleppo. His Faulkneresque switching of tenses in fiction, a style some critics have called Arabesque, indicates where many Syrians find themselves today. This ongoing past of brutality and disinformation bloodies the present.

During this trying period, there is an understandable tendency to search for the deeper trends that have led to a society-wide breakdown. The Syrian researcher and thinker Hassan Abbas has contributed the critical essay Between the Cultures of Sectarianism and Citizenship, which examines the battle lines that have been drawn in the country today. One example of Abbass inclusive definition of citizenship appears in the form of new banners and signage created in Syrias sixth-largest city, Deir al-Zour, by Kartoneh a collective of activists who are exploring a new language of inclusiveness. Another Syrian collective, Alshaab alsori aref tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), has been producing political posters and making them available online for activists to download, print and carry during demonstrations. As cited in art historian Charlotte Banks essay, their imagery follows a long aesthetic tradition of political posters from the Soviet Union to the Lebanese civil war. As opposed to the essentially monolithic propaganda of the regime, this anonymous group has spearheaded a growing movement of multidimensional revolutionary symbolism that has encouraged dialogue, debate, free expression and contestation. The meanings behind the representation employed by both the regime and the uprising are examined in co-editor Zaher Omareens essay, The Symbol and Counter-Symbols in Syria. All across Syria, cities and small towns have been developing their own visual vocabulary of resistance none more so than the tiny hamlet of Kafranbel, where the witty cartoons photographed for this book by Mezar Matar come from. These works, often humorous yet always serious in intent, illustrate Kafranbels take on events and the failure of the international community to respond.

Another defining factor of the Syrian uprising has been the army of citizen-journalists who have posted over 300,000 videos, films and other visual material on the Internet, depicting what has been taking place in their country. They would not have been so well equipped or organised if not for the Local Coordinating Committees (LCC s), a network of clandestine activist cells and groups operating across the country. For the first time, Assaad al-Achi, who was responsible for obtaining spycams, laptops and software from abroad and smuggling them into Syria, reveals the shopping list of citizen-journalists operating from inside. This interview is accompanied by Omar Alassads survey article on the countrys alternative media scene, which has spawned local newspapers, new radio stations and even clandestine television stations, despite the violence. Another powerful example of this alternative media perspective has been the local documentary and global artistic aesthetics of the Lens Young anonymous photographers collective and its associated groups across Syria.