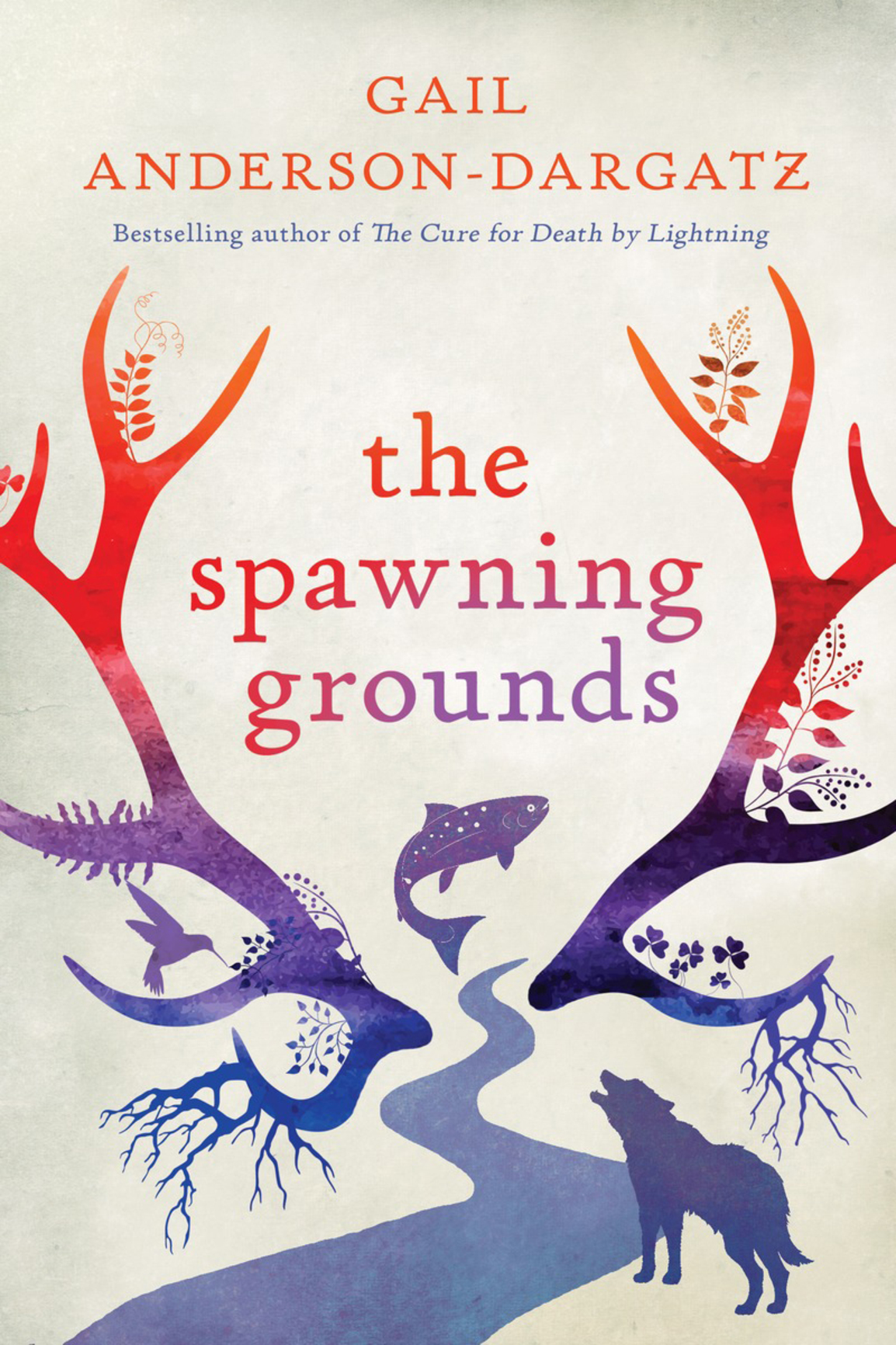

the departure of the spirit.

Advent

September 1857

EUGENE ROBERTSON WOKE in his tethered dugout to a thunderous rush, as if the river had let loose a flash flood upon the narrow valley floor. But the furor travelled upriver, not down, and the wave that lifted and pounded his boat was not made of water.

He sat up and peered into the current, then immediately recoiled: multitudes of dark forms swam under him. For a dream-laden moment, these strange spectres were the water mysteries the Indians had warned him of. Like the water sprites of his homeland, these spirits would drag a man down into their world, a land that in many ways mirrored this one but was home to creatures that were neither man nor beast, but both, as in the beginning. Pictographs of these spirits covered the cliff face upriver, above the narrows. Lichen and the roots of trees growing, incredibly, off the cliff surface, covered many of the images. One was still clearly visible, though, even to Eugene sitting in his dugout this far downriver: a huge zigzag painted on the cliff face, a red lightning bolt. A creature sprang from the lightning, part fish, part man, surrounded by sketches of the bones of salmon. On Eugenes arrival that summer, one of the Indians had warned him to stay out of these waters or he would be taken by the spirit that haunted the river at this place.

Eugene thrust a hand into the dark waterinto his irrational fearand felt them there, sliding against his fingers, these terrible phantoms with their gold eyes, fang-filled jaws and monstrous humps on brilliant red backs. The sockeye salmon had returned. Flying overhead or perched on scrags that lined the river, hundreds of eagles had arrived to feed on them.

The river was thick with salmon, red with them, from shore to shore. Here was the biblical plague, Eugene thought, the river of blood. The noise the fish made as they fought their way upstream was the rumble of an oncoming squall, the collective splash and slap of thousands upon thousands of bodies upon bodies, tails beating water, as they thrashed in their struggle to the spawning grounds. When the throng of fish reached the white water at the narrows, the rapids slowed their advance upriver. Unable to breathe in the waters now starved of oxygen by the smothering number of fish, the sockeye panicked and rushed back downriver, where they met the fish travelling upriver behind them. Eugene fell backwards in his boat as it heaved up on the mass of undulating fish, a red tide of sockeye, their bodies spilling out of the riverbed and onto shore.

Eugene Robertson wasnt the first white man to fish this riverthe fur traders had been coming for decadesbut this past summer, the summer of 1857, he was the first to stake a claim along its rocky shore; the first to muddy its waters with a gold rocker in his hunt for riches; and the first of the many miners who followed within the next five years, eating the salmon and stirring the silt of this river so that it blanketed and suffocated the sockeye eggs as they slept in their gravel nests. The miners would all but wipe out the salmon run; the fish would never return in such numbers. When the other miners had taken what little gold they found and moved on, Eugene became the first of the homesteaders to call the shores along the Lightning River home; the first to take down trees on the thin strip of river plain; the first to put up fences; the first to water his livestock from this river and pollute its waters. Each future generation of Robertsons would take more from this river and this land. And Eugene was the last white man to witness this miracle on the river, the mass return of the sockeye.

He righted himself in the pitching boat, then removed his suspenders, jack shirt and pants, his long underwear, and sat for a time watching the fish writhing around him. In the milky morning light, his ginger hair glowed and his muscular body shone white. A drift of freckles ran along his shoulders and down his arms and legs. Already, dragonflies hovered over the shallows where his boat rocked, flitting like winged folk, the capricious woodland faeriesthe old godsof his grandfathers stories. They darted away as he slid from the dugout into the water, into a river made almost entirely of fish.

The salmons skin was slippery and cold and yet Eugene grew erect from their jostling against him. The water, like the air above it, was charged, electric, permeated with the overpowering smell of salmon, of ocean, of sex. In the sky over his head, two eagles shrieked and flew together, grappling with their talons. They fell, cartwheeling, and only pulled apart as they were about to hit water. As the eagles flew back into the air, Eugene saw a boy ascend naked from the river, as if lifted by the eagles, to stand on the surface of the water. The panic that had gripped Eugene on the sockeyes arrival returned. Surely this was no human boy, though he appeared to be. He was perhaps fifteen or sixteen, no longer a child, not yet a man. The salmon leapt all around him, frenzied, as if rejoicing in his presence. Yet it was Eugene the boy watched intently and not the fish. Eugene wiped the water from his eyes as he struggled to keep the strange boy in view, but the countless salmon spun him and carried him around the rivers bend. For a moment, Eugenes soul was adrift. He was water. He was fin. He was fish.