Adam Weymouth

KINGS OF THE YUKON

An Alaskan River Journey

PARTICULAR BOOKS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Particular Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Adam Weymouth, 2018

Illustration and map by Ulli Mattsson

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design: Richard Green

Author photograph: Suki Dhanda

ISBN: 978-0-241-27041-7

To you, as yet unnamed, who came along quicker than this book

And to Mum and Dad, for always trusting that I knew what I was doing

the generations that came before, the generations coming after

Wait, I see something: We come upstream in red canoes.

Riddle of the Alaskan Athabascans, documented by the missionary Julius Jette (18641927)

rival (n.)

from the Latin rivalis, one person using the same stream as another

Authors Note

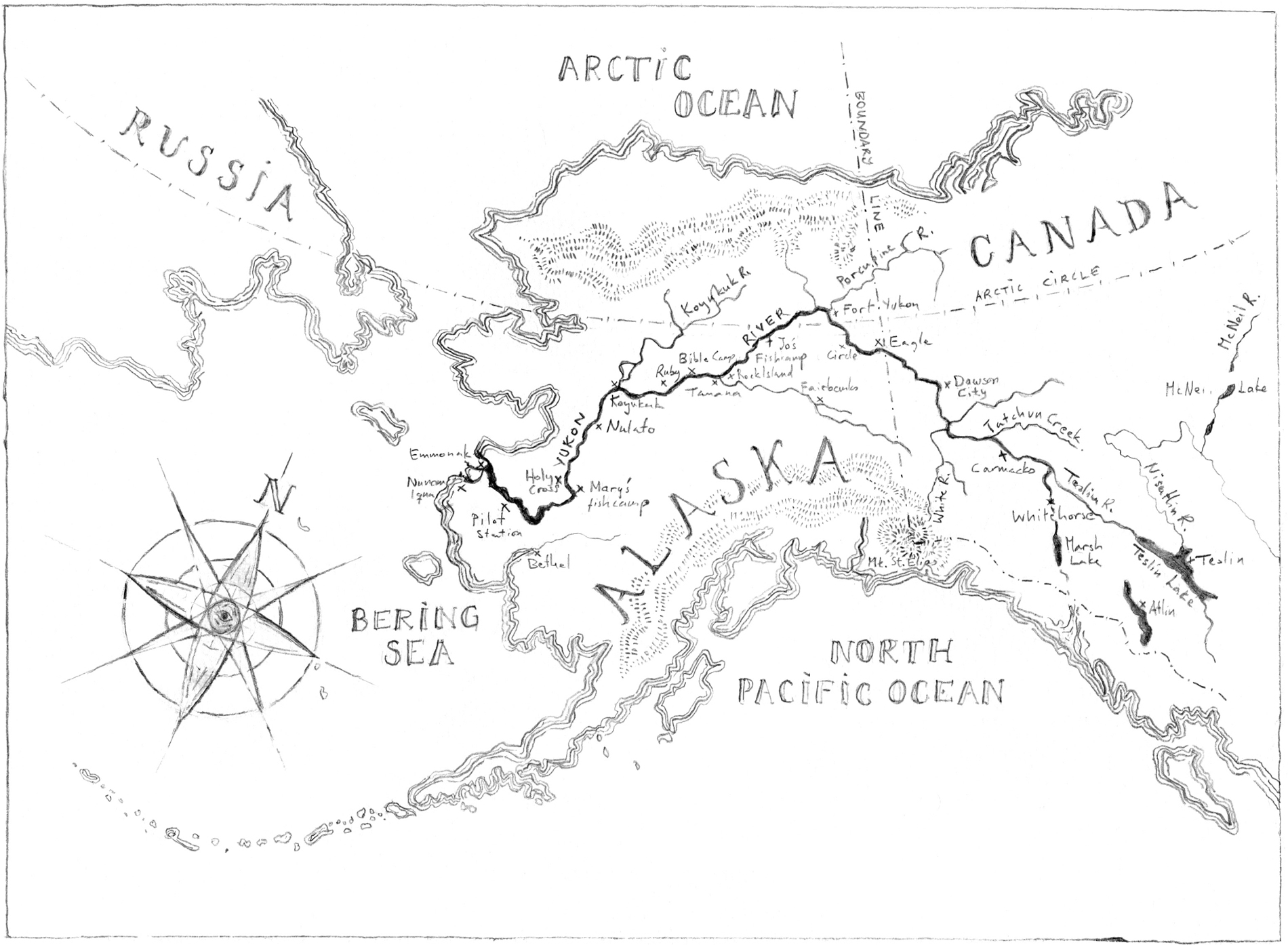

There are five species of salmon found in Alaska and Western Canada. This book is concerned predominantly with one of them, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha, generally referred to as the king in Alaska and the Chinook in Canada. I have used these names interchangeably throughout.

Whilst the majority of the research for Kings of the Yukon was carried out during the summer of 2016, I returned to the Canadian side of the border for a shorter trip in 2017. One summer in the North is simply too short a season to cover the two thousand miles of river that the salmon span between break-up and freeze-up. I have, however, written about the trip as one continuous journey, in order to preserve the flow of the story. All data on escapement numbers, sex ratios, etc., relates to the 2016 season. Most interviews were recorded by hand, either at the time or afterwards; several were recorded on audio. Some characters names have been changed to protect their privacy. Interviews in Canada were carried out according to the Traditional Knowledge policies of the First Nations involved, policies which strive to protect their cultural heritage from exploitation.

The terms Eskimo and Indian are often considered pejorative, yet are commonly in use in Alaska and Canada, amongst both Indigenous and white people. Alaskan Native and First Nation are not able to differentiate between these two very separate groups, and they do not encompass the connection, on the Eskimo side, between other groups that inhabit the circumpolar region, and on the Indian side, with other native peoples of Canada and the Lower 48. As such I have occasionally used them in the book, alongside the proper names of specific tribes and clans. Whilst the word Indian is commonly assumed to derive from Columbus believing that he had reached India, figures such as the activist Russell Means and the American Indian Movement offer an alternative etymology, described here by Cree lawyer Harold R. Johnson in his book Firewater: Columbus was not lost, he knew where he was, and he called us In Dios, meaning with God. The word is not as important as the story we tell about it. Indian is also a precise legal term found in our Treaties and the Canadian constitution.

Finally, for reasons best known to themselves, Alaskans call a snowmobile a snowmachine. A snowmachine is not for making snow, as it is everywhere else in the world, but for driving on it. It is the word I have used here.

The river is flowing backwards, back up from the sea.

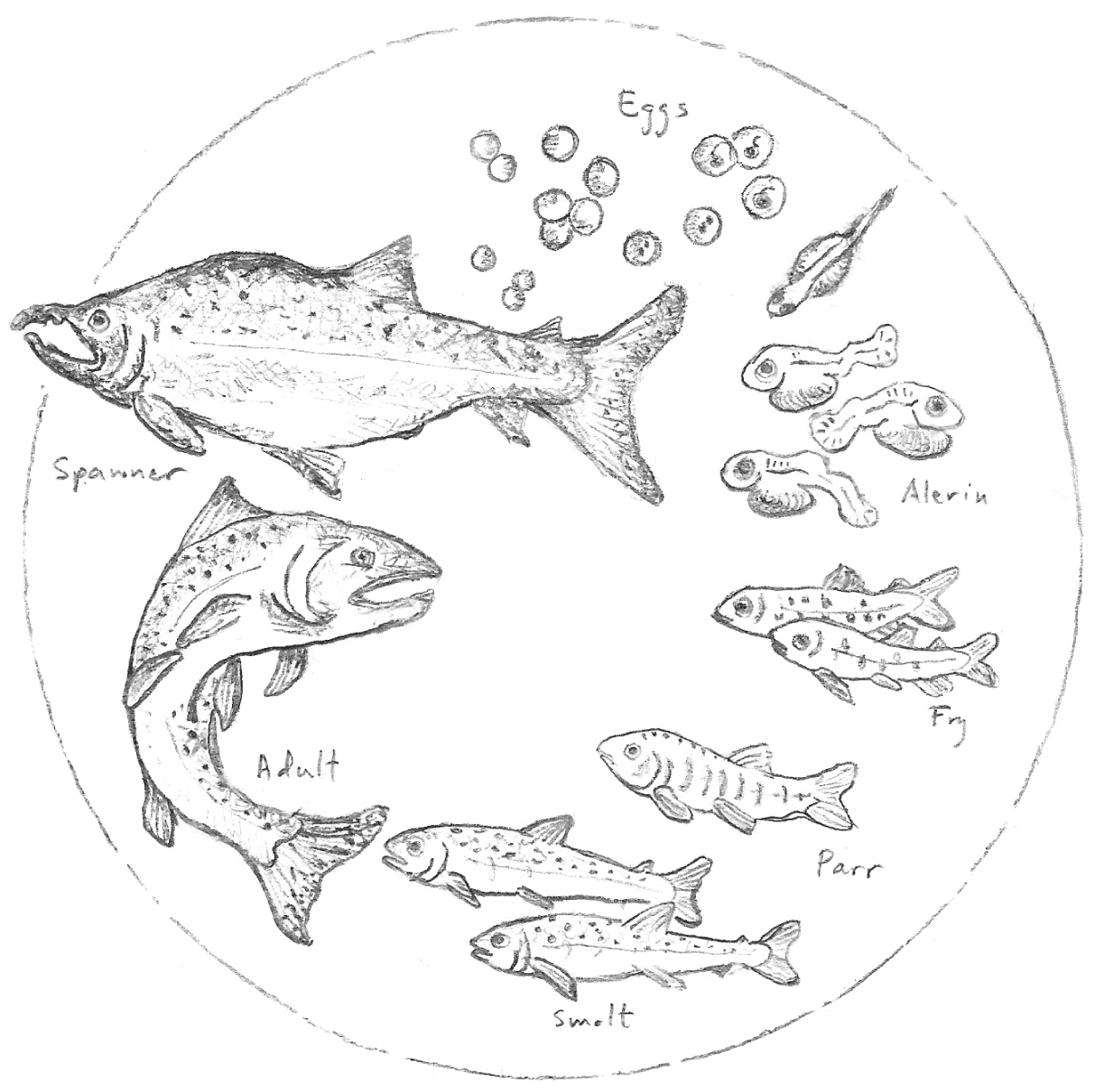

They swim through silt, eyes wide, unblinking. Thirty, forty, fifty pounds of flesh, many thousands of them. Their backs speckled like frogspawn, the blush of their bellies, where the silver of their flanks fades into a deep and meaty rose. Jaws gawping, lips beginning to curve in upon themselves like pliers, propping their mouths ajar so that the river flows right through them, and yet for the rest of their lives these salmon will not eat, they will not drink. The organs that sustain them, the kidneys and the stomach, are shrinking as they sense the sweet water they have not known since they were smolts, finger big, years back. Familiar scents long forgotten are triggering changes in their brains and in their bodies: their chemistry has new priorities now. The ovaries of the female hen will swell to a sixth of her bodyweight during her swim upriver, the cocks testes will increase fivefold.

For several years the salmon have roamed in schools throughout the Bering Sea, the chain of the Aleutians, the Sea of Okhotsk, ranging as far as the coasts of Japan. Their many species mingle. They travel further than science can reach, and much of what they eat and where they winter can only be surmised. The Yupik say that they live in human form beneath the waves, five houses, one for each tribe, and at the salmon kings behest, each spring, they pull on their fins and silver skins and make for the human world. In the late Arctic spring, impelled before the others, the kings turn for North Americas west coast. California, Oregon, Washington, British Columbia, Alaska. They have iron in their brains, their compasses have led them here; now they scent their birthing pools. A chemical mix of vegetable and mineral unique to the waters of their birth that draws them on a thread up several thousand miles of river. They can distinguish a single drop from their home river amongst two million gallons of seawater.

The movement of one, changing direction, pulses through the rest, electric. At times they crest the surface, a dark sleek back, a dorsal fin, undulating like dolphins. These fish are many pounds of muscle, toned through years of swimming headlong into Pacific storms, and their flesh is red as blood. They force against the Yukons current, shouldering their way upriver, tacking crosswise through the flow, setting their fins like sails. Their shadows pass like clouds across the bottom. They rest in the eddies of boulders on the rivers bed, erratics left behind by glaciers. At the rivers mouth the water is still brackish, the current compounded with the flow of the tide. But it is diluting, and as they move further up the delta the sea slackens off its hold, resigning, letting them go. On this great in-breath of the land the kings spread up through the waters and their tributaries, permeating the watershed. Eventually, they will push thousands of miles into the continents interior. They will reach mountain lakes, they will reach the clouds.

It is the end of May, and spring is late. Which is not to say that it is a late spring, because this far north there is no such thing as a yardstick to measure the seasons up against (Ive been here fifty years, in the words of one old-timer, and the only normal year we had was two years ago), but people say it is not where it ought to be. Mountains ring the town, and the snow still comes far down their peaks. The dandelions only opened last week. Bears have awoken from hibernation and, finding nothing to eat, have roamed within the Whitehorse city limits, sniffing out trashcans and chicken coops. The government has shot six in the past month.