RECOVERING A LOST RIVER

Removing Dams,

Rewilding Salmon,

Revitalizing Communities

Steven Hawley

BEACON PRESS BOSTON

Contents

For Elliot and Annabel

Expect poison from the standing water.

WILLIAM BLAKE, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Prologue

The seeds for this book were fertilized years ago, when I poisoned a dozen people on a float trip through Hells Canyon. Missoula, Montana, my home then, was less than a days drive from some of the worlds greatest rivers. So great in fact, that they require you win the lottery to get on any one of themthe United States Forest Service lottery, which determines which lucky contestants get to launch on the Middle Salmon, Main Salmon, Selway, and Snake rivers. Although the Snake, or rather the last free-flowing portion of it through Hells Canyon, is considered something of a consolation prize in this four-river draw, any chance to float through these wild places is usually taken by the free-thinking and free-spiritedcome hell or high water.

This scenario creates an unusual, perhaps unprecedented circumstance in modern-day travel: the lottery winner, upon whom luck has smiled, often feels obliged, or perhaps is coerced, into sharing her good fortune by inviting a few friends, who in turn may invite a few more friends. Before long, a loose affiliation of folks whose backcountry capabilities, quirks in personality, peccadilloes in daily habits of living, or prior arrest records are unknown to one another will embark on a weeklong adventure through a stretch of country where cell-phone reception remains a space-age fantasy.

This was such a trip. We loaded a convoy of cars with rafts, tents, sleeping bags, sleeping pads, guitars, kayaks, a solar shower kit, a first-aid kit, paddles, oars, Frisbees, a Wiffle ball and bat, coolers, folding tables, folding chairs, a portable privy, fishing rods, life jackets, helmets, a full-service kitchen and bar, and an item that later proved to be indispensable, a hand-cranked stainless-steel blender.

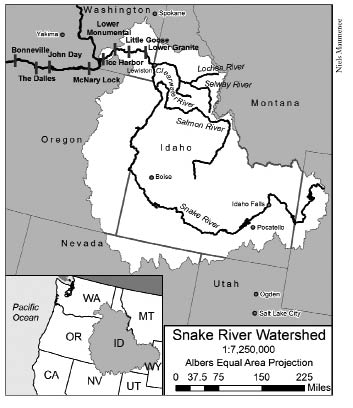

Right away, our group showed great courage and self-discipline: it was the zenith of summers heat, late July, and no one even mentioned getting into the coolers of beer until we were almost a third of the way to the put-in. Already, we had traveled a long way: from Missoula, west down twisted Highway 12, following the Lochsa River to its confluence with the Selway, where the Clearwater commences, then on to Kooskia, Idaho, where the South Fork of the Clearwater meets the main stem. We skipped rocks in the river where these two currents meet, then proceeded on: up the South Fork, up the Harpster Grade to Grangeville, then over Whitebird Pass, and on down into Salmon River country; the Seven Devils on our right, the Salmon-Selway wilderness on our left. In a mood of anticipatory delight, we stopped to swim at a white-sand beach adjacent the river, then rested in Riggins.

We then moved up the road along the Little Salmon River: eventually on to Council, then Cambridge, up the grade called Brownlee Summit, and down once more to Oregon and the fetid slack water behind Oxbow Dam on the Snake River. The end of the days long drive, a cursory tour of the edges of the largest tract of wilderness in the Lower 48, proved to be something of a disappointment: here lay what used to be a wild river, the upper portions of Hells Canyon.

At the well-manicured turf-and-concrete campground below the dam, graciously provided by Idaho Power as reparation for the missing river, we had finally arrived. We had missed the dinner hour by a long shot, and a hungry crew was grumbling in the gloaming about getting some food down their gullets and getting to bed. Almost everyone was there, except the guy with the full-service kitchen and bar in the back of his truck.

I alone faced a minor public health dilemma. For dinner that night, I had prepared in advance a simple Mexican dish, chicken mole. The custom was simply to buy a whole chicken, boil it for an hour, place it on a platter, prepare the mole sauce, place that along with the salsa, cheese, onions, sour cream, and other trimmings in buffet-style bowls, and let dinner guests create their own sweet burritos. That was the usual procedure, but in the rush to pack everything in, I found it necessary to take some shortcuts that proved to be costly. In an effort to save cooler space, I carved the bird in advance, placing the strips of meat in the sauce, sealing the whole affair into a giant plastic container. Arriving upon the chaos of the group packing, I discovered all the coolers were full: no matter, I would shuttle home, grab another cooler, put the evenings repast on ice, and all would be well.

Dont bother, weve got seven coolers already, someone had said.

Regrettably, I didnt act on this simple leap in rational thought: seven coolers, all full to the hilt, so an eighth would be required on a ninety-eight-degree day to get dinner safely to its destination. I shrugged, capitulated to the notion that seven coolers were enough, and the plastic container traveled uncooled for the duration. I noted with silent concern on several occasions over the journey the signals of a volatile chemical reaction. As I glanced furtively through the transparent plastic, the contents therein appeared to be boiling still, just as they had been when transferred that morning.

As darkness descended on our starving contingent, I made an executive decision: we could not eat until the chicken was heated. Eyes rolled. Several people stomped off in the dark. One woman was moved to tears. So wheres the stove? someone asked.

Its in Garys truck.

Where the fuck is Gary?

Who the fuck is Gary?

I think they went to the put-in.

Thats seventeen miles from here.

Great. How about a little drive?

Once again, we proceeded on, sending one car speeding ahead. After what seemed like an hour, we met our pilot car coming back the other way.

I couldnt findm, man, no sign.

Should we drive back?

We should just eat.

I felt the eyes of a half-dozen perfect strangers burning into me. I popped the lid on the chocolate chicken. It smelled fine. I dipped my finger in the sauce. It tasted even better.

Screw them. Lets eat, I said.

With blazing efficiency, two tables were set up on the roadside, dinner was laid out, and a gaggle of happy campers were stuffing their faces. Moments later, Gary pulled up, headlights blinding.

We saw your car, dude, you drove right past us, he explained. We were at the put-in, wondering where everyone was, and saw you and figured wed better backtrack.

Thanks for sticking with us, someone mumbled sarcastically in the darkness.

An awkward silence ensued.

Wow. Cold chicken burritos, Gary observed.

Not exactly cold.

Not exactly hot.

Shut up, whiners. The beers cold.

Mellowed with full bellies, we decided there was enough room for all of us to camp right where we stood, at a wide spot in the road, on a concrete slab near the edge of a reservoir that looked like it had been used for staging equipment during the dams construction. One couple argued about how to set up a tent on cement. Another griped about the eight goddamn hours it had taken to get here. An ominous tension cast a pall over the evening.

I decided a solitary stroll was in order. I tried to let the complications of the group dynamics roll off me like water off a ducks back. Thoughts drifted along in the night, sluggish as the rivers current between two dams.