Contents

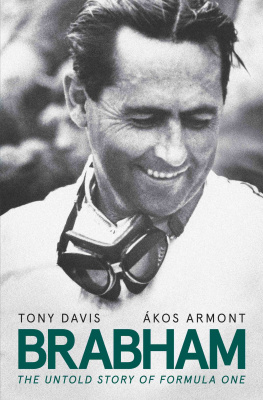

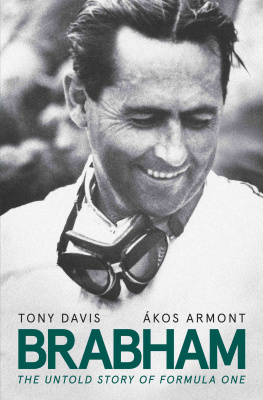

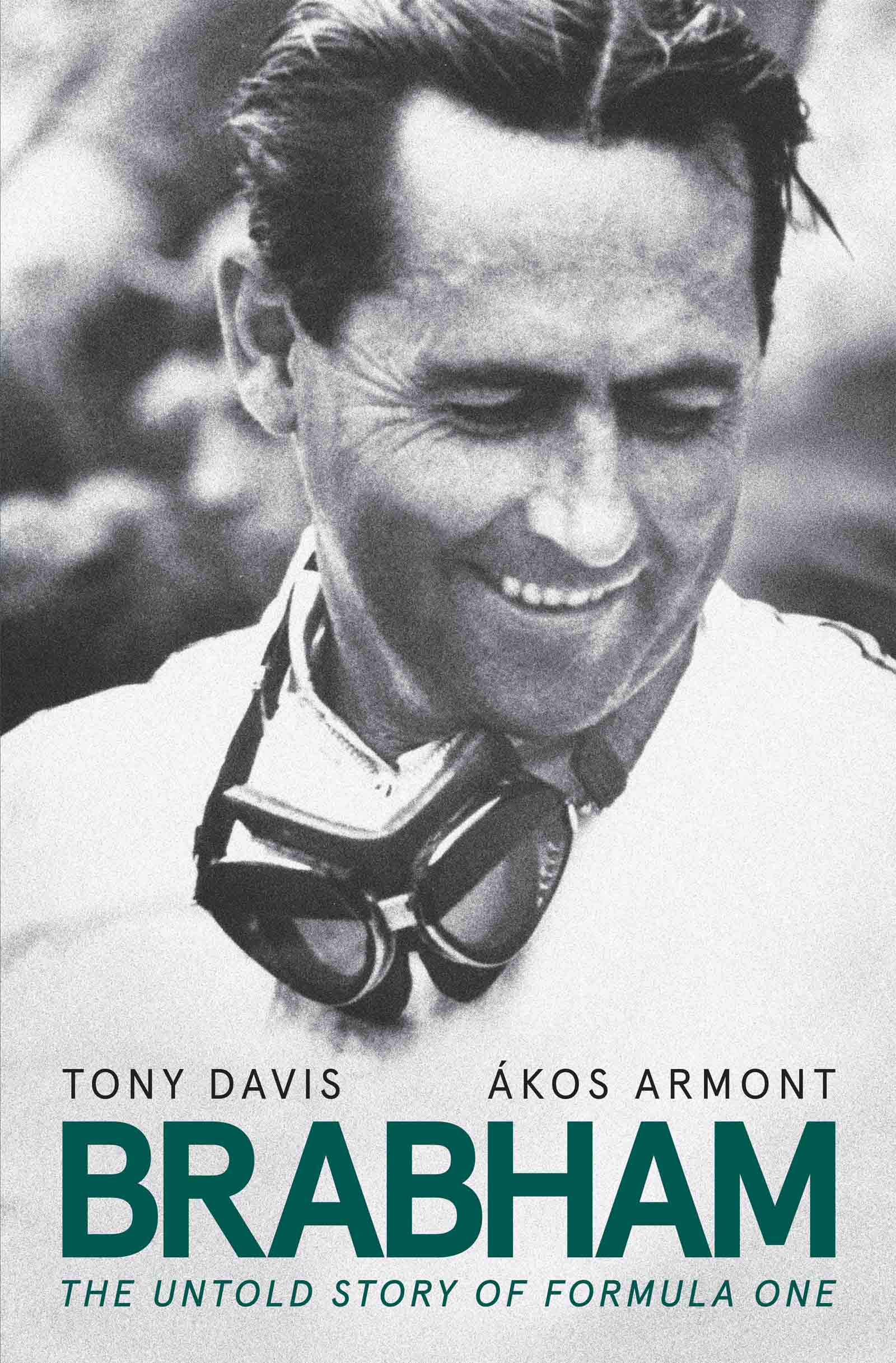

I t seems surprising that, until now, no one has written a book-length biography of Jack Brabham (19262014). During his lifetime there was a trio of ghostwritten autobiographies (1960, 1971 and 2004), each borrowing in part from the previous one, and each interesting in its own way. Now, exactly sixty years since the iconic Australian driver won his first Formula One world championship, comes the first book giving an outsiders view of the acclaimed driver, car constructor and innovator who so dramatically changed the motor sport world. It draws on a wide range of sources including interviews undertaken by the authors and others over the years, contemporary magazine and news clippings, biographies and autobiographies of other drivers, marque histories, videos, race reports, the three Brabham memoirs, plus the extensive new interviews undertaken for the film Brabham. Jacks sons David and Geoff have also cooperated closely.

Unless otherwise labelled in this text, or via an endnote, all quotes from David and Geoff Brabham were drawn from exclusive interviews for the 2019 Brabham film and book project. Likewise, those from Ron Tauranac, Stirling Moss, John Surtees, Ron Dennis, Doug Nye, Hughie Absalom, John Judd, Jackie Stewart, Mark Webber, Lisa Brabham, Matthew Brabham, Sam Brabham, Bernie Ecclestone, Nobuhiko Kawamoto, Mark Bisset and Iain Curry. Jack Brabham and Ron Tauranac were also interviewed by Tony Davis for the Wide Open Road documentary series and book in 2011, and parts of these interviews have been incorporated in the text. The source for each substantive quote from Jack Brabham is noted, though for ease of reading, short quotes are not attributed.

Where material has been drawn from other publications or interviewers, it is acknowledged accordingly. Comprehensive interviews with Denis Hulme and Frank Matich were conducted by Michael Stahl, in 1991 and 2012 respectively, and generously made available to us. Parts of Stahls revealing 2013 interview with Ron Tauranac have also been incorporated and labelled accordingly.

Please note that the subject of this biography is often referred to in this text simply as Jack. This is not to be overly familiar with the man, but to reduce confusion with the brand of car, the racing team and the other companies and organisations that bore his surname.

J ack Brabham was flying his own Beechcraft Queen Air back from the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Hed won four Formula One grands prix on the trot and this should have been the fifth. He was at the top of his game despite being forty years of age. He was still matching the raw speed of F1 drivers almost half his age, and doing so in a brilliant car built by the company he had founded, with his surname on the badge, and a Repco V8 hed helped develop providing the power.

At the dauntingly fast Monza circuit, the spiritual home of Ferrari, hed been showing up the fancy V12s that the Italians were so proud of. But his car started gushing oil and he had to surrender his lead and watch the red machines he hated take first and second places.

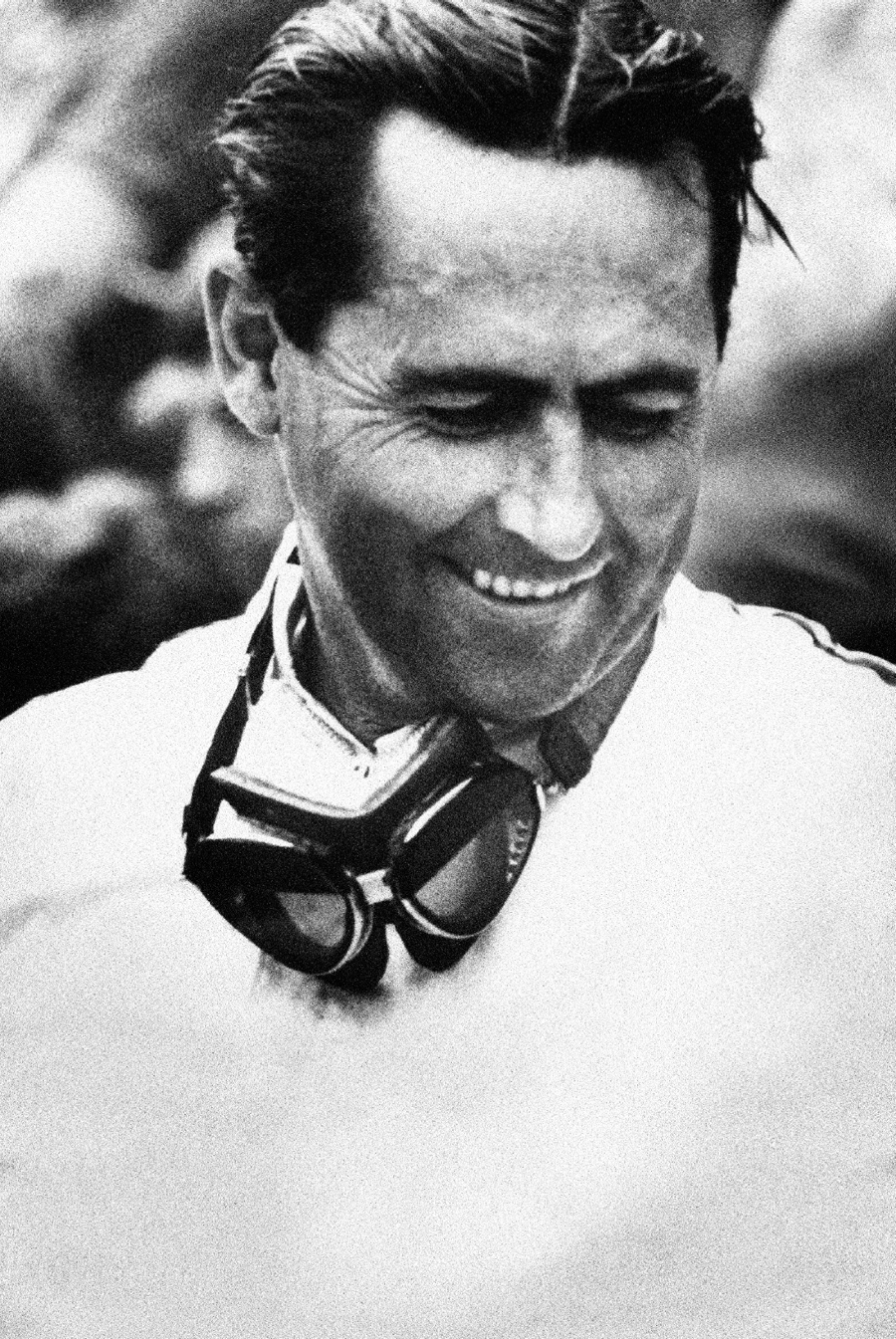

Next to the dashing Italians, the brash Americans, and the British drivers with their clipped tones and media smarts, Jack Brabham was a man apart. He was older than all of them and the swinging sixties had made no mark. His hair was still short and slicked back, his wardrobe dated and in the muted colours of the preceding decade. Hed arrived in the UK in the mid-1950s as a grease monkey, which is to say a driving mechanic, in a sport dominated by gentlemen, or those who could do a good impression of one. His first UK employer, John Cooper of the Cooper Car Company, would tell people hed found this wild man from the Australian bush who didnt know how to use a knife and fork.

Brabham didnt help his own cause by talking without moving his lips, if he talked at all. The British press called him Chatty Jack, because he wasnt. Another nickname almost certainly from John Cooper was Black Jack. If you were being polite, that related to the dark hair, nut brown complexion, and five oclock shadow. If not, it referred to the blinkered, brutal competitiveness that overtook him the moment he put on a race helmet.

His on-track aggression, combined with sublime car control, had won respect from peers and critics, initially begrudgingly, by now almost universally. His cars too had become favourites; the strong, sleek, simple machines were so respected there had been four Brabham customer cars lining up on the grid at the recent British Grand Prix, as well as the two works cars. Brabham in a Brabham had won that race, ahead of New Zealander Denis Denny Hulme in another Brabham.

One reason the Brabham cars were so good was that Jack had a brilliant if eccentric designer-engineer running his operation. His name was Ron Tauranac and he was now sitting in the Queen Air with Jack, heading for the tiny English airport near their factory. Tauranac was tall, painfully thin and often surly, and his prominent top front teeth and long nose also helped give him a slightly Dickensian appearance. He and Jack had worked together since the 1950s and, in the 1960s, the pair had built hundreds of cars that were winning in almost every formula. At the end of most post-race flights like this, theyd go straight to the factory to put in a few more hours work. Yet as they approached the landing strip, Tauranac noticed there was an unusually high number of cars parked between the low World War IIera buildings that lined the edge of the airport, and a crowd of people milling around, as if waiting for this very plane. Tauranac later recalled, I said, Whats all this about, Jack? and he said, Oh theyre all the journalists. I said, What for? He said, Weve won the world championship.

The two other drivers with a chance of being world champion for 1966 had retired at Monza, so Jacks large points lead was now unassailable. His third world drivers championship was in the bag. I never used to look at points or anything, recalled Tauranac. I hadnt realised that when hed retired, hed been in an unbeatable position... I didnt know wed won. I was only interested in what I could do next on the car.

So it was: these two extraordinarily talented but taciturn men rarely discussed even the most essential parts of their world-beating partnership with each other, let alone outsiders. In Rons words, I wasnt very good at talking and neither was Jack. Yet together they achieved a double win that will almost certainly never happen again: a driver had taken his own brand of car to victory in both the F1 drivers and constructors championships in the same year. And they did it with an engine built by a company on the other side of the world, in its very first year of F1 racing.

S ome saw it as inevitable that Jack Brabhams three sons would go racing. But not the man himself, nor his wife Betty. At the end of Jacks F1 career, the couple moved from England back to Australia to take the family away from the motor sport scene. That was the plan, anyway. But Jack took on a car dealership, and it owned a small open-wheeled race car. Eldest son Geoff, just out of his teens, eventually persuaded his reluctant father to let him have a go.

My dad peered into the cockpit, remembers Geoff, and said, Okay, theres the brake, theres the throttle, theres the steering wheel, if you crash it, dont come back. My whole career... he never, ever gave me any other advice, other than that.