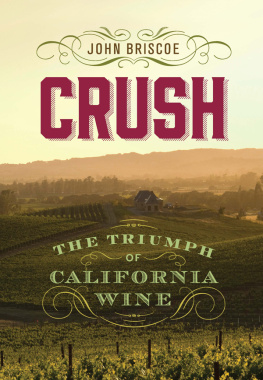

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

Asher, Gerald.

A carafe of red / Gerald Asher.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-520-27032-9 (cloth, alk. paper)

1. Wine and wine making. I. Title.

TP548.A787 2021

641.2'2dc23 20110274210

In keeping with its commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Book, which contains 30% post-consumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z 39.481992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Map 1. Wine regions of France

Map 2. Wine regions of Europe

Map 3. Wine regions of Napa Valley

INTRODUCTION

Long ago, during my apprenticeship in the wine trade, I learned that wine is more than the sum of its parts, and more than an expression of its physical origin. The real significance of wine as the nexus of just about everything became clearer to me when I started writing about it. The more I read, the more I traveled, and the more questions I asked, the further I was pulled into the realms of history and economics, politics, literature, food, community, and all else that affects the way we live. Wine, I found, draws on everything and leads everywhere.

Those leads run through the chapters of this book. Each stands alone, yet each sheds light on an aspect of wine that will, I hope, add to your understanding of it. The very firstA Carafe of Red, which gives its name to the collectionis a conversation that summarizes two thousand years of winemaking in France, from the first Roman colony to today's republic, explaining along the way how religion and politics, the Industrial Revolution, transportation (canals and railways), and the ravages of phylloxera helped shape the nature of French wine. Malmsey gives a glimpse of international trade and politics in the Middle Ages, while Ctes de Castillon, a tale about the revival of a Bordeaux wine, looks behind the town's official name, Castillon-la-Bataille, to the battle fought there in 1453. Heavy artillerygiant cannons hidden on a hillside above the battlefieldwas used for the first time to mow down knights in armor. While bringing an end to England's territorial aspirations in France, it also brought an end to the chivalryof the Middle Ages. Like a bookend to that historic moment, Castillon's winemakers have also been at the forefront of modern wine technology. They were among the first to adopt micro-oxygenation, a technique emblematic of their determination to improve the quality of their red wine, an effort so successful that Castillon wine leapt to the cover of Le Point, the French news magazine, where it was classified among the ten best wines of France. In Jerez de la Frontera, I give you a glimpse of microbiology in action in the veil of Saccharomyces that plays a key role in the development of Fino Sherry, while A Silent Revolution, about the meaning of organic viticulture, looks at the role microbes play in keeping us fed. Small things often have large consequences: the spark of a weekend escape for a few writers and painters from nearby Tarragona, caught by a magazine article coinciding with the Barcelona Olympics, lit a passion that has brought back to life Priorato, a Catalan wine region on the verge of extinction, yet now producing one of the most sought after red wines of Spain. The chapter Haut-Brion shows how Bordeaux wine was transformed from tavern tipple into the yardstick by which other wines are measured; in Judgment of Paris that yardstick has historic consequences for California. In Missouri I show how the German American culture of that state evolved alongside its early viticulture; and Chardonnay, in recounting the origins of one variety's clones in California, illustrates, in effect, the significance of all clones of all wine-grape varieties everywhere. And in A Memorable Wine, I reflect on the question often asked of me and others who have led a life professionally involved with wine: What is the best wine you can remember? The answer to any such question can only be subjective, of course. What is best for me, or anyone else, depends on personal preference, the context, and our mood at the time. But above all, it depends on the knowledge and the personal memories we bring to the wine in the glass. It's what we bring to it that can make even a supposedly simple carafe of red memorable. That's the purpose of this book.

Gerald Asher

San Francisco, August 2011

A CARAFE OF RED

W e had stopped for a quick lunch at a pastry shop near the Place de la Madeleine. My friend sniffed approvingly at her glass of red wine. This is good, she said. What is it?

It was from the Corbires, the block of wind-riven mountains between Carcassonne, Narbonne, and Perpignan on the French Mediterranean coast. While the world has been looking elsewhere, the growers of the Corbires have been busy recapturing for their wines a reputation that had always distinguished them from those grown elsewhere in the Languedoc. My friend was right: The wine was good.

And what did she think of the Bonington watercolors we'd seen that morning at the Petit Palais? She knows far more about pictures than I do, but she brushed Bonington aside. Is that all you're going to tell me about the wine? she asked.

How much did she want to know? The Corbires is the oldest wine region of France. Its story is virtually the story of French wine.

Why don't you start at the beginning, she suggested. So I did.

The Romans planted their first vineyards in the Corbires soon after they built a harbor at Narbonne. In passing a decree establishing the colony in 118 b.c., the Roman senate had intended to secure for Rome the passage from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic by way of the Aude and Garonne river valleys. It was the route by which wine, much prized by the Celts, was bartered for Cornish tin. Rome, ever belligerent, neededtin to produce bronze for weapons and preferred to see her enemies (and victims) deprived of it.

The Seventh Legion was sent to protect the traffic (hence the region's ancient name of Septimania), and veteran soldiers, usually married to Celtic women, were encouraged to settle there when they retired from active service. It was probably veterans who planted those first vineyards. But they chose to trade their wine not to Cornwall but back to Italy in exchange for the small luxuries only Rome could provide. There, their wine was so highly prized that Rome's speculators rushed to extend the vineyards. Wine from Septimania was soon competing successfully with that grown on the Italian estates of Rome's most powerful families. Cicero reported the furious debates in which senators demanded that the vineyards and olive groves of Gaul not be allowed to render their own valueless. The emperor Domitian was prevailed upon in A.D. 92 to order half of them ripped out.