Conversations with Buuel

Interviews with the Filmmaker, Family Members, Friends and Collaborators

MAX AUB

Translated and edited by Julie Jones

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

This book was originally published in Spanish as Conversaciones con Buuel in 1985 by Aguilar in Madrid, Spain.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2755-7

1984 Max Aub and Heirs of Max Aub

Translation and annotations 2017 Julie Jones.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

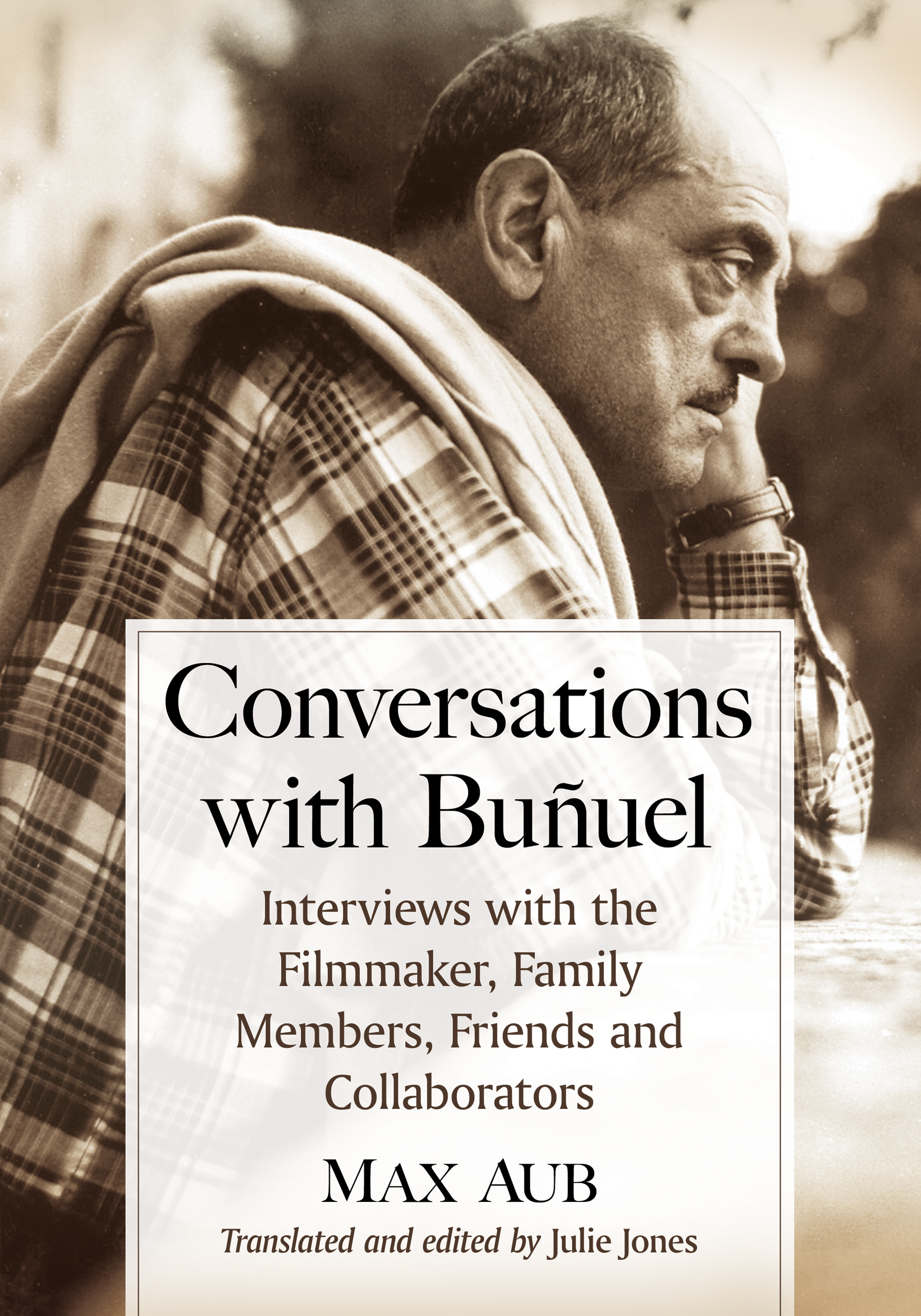

Front cover photograph of Luis Buuel by Carlos Saura

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Translators Acknowledgments

I want first of all to thank Teresa lvarez Aub and Elena Aub Barjau for allowing me to publish this translation and general edition of Max Aubs work, and Teresas father, Federico lvarez Arregui, editor (and he alone knows how much work that entailed) of the original publication, who encouraged me in this endeavor and provided as many answers as he could to my repeated questions. In spite of her busy schedule, Carmen Peire, editor of Buuel, novela and author in her own right, was kind enough to put me in touch with the Aub family. I also particularly want to thank Mara Jos Calpe of the Fundacin Max Aub. Mara Jos received me very generously at the Fundacin in Segorbe in 2014. Since that visit, both she and Francisco Tortajada have helped me with innumerable requests.

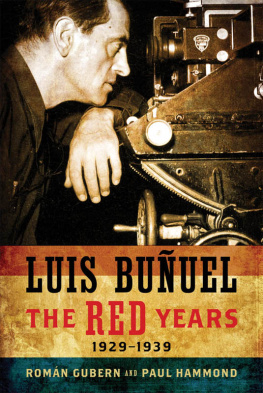

In addition, I am particularly grateful to the Buuelistas whom I have peppered with questions and more questions and who have unfailingly provided answers when possible or made suggestions when not, always with the greatest patience. Romn Gubern, Paul Hammond, Javier Herrera and Fernando Gabriel Martn are those on whom Ive called most often, but Ive also received significant help from Agustn Snchez Vidal, who has encouraged my Buuel obsession over the years, Juan Luis Buuel, who received me generously in Paris and always answers my emails, Ian Gibson, Amparo Martnez Herranz, Ral Miranda of the Cineteca in Mexico, Alfredo Valverde of the Residencia de Estudiantes and the people at the Filmoteca Espaola, especially Immaculada Salvador and the invaluable Marga Lobo. Finally, I am very grateful to the filmmaker Carlos Saura, who has kindly given me one of the many fine photographs he took of Buuel over the years to use on the cover of this book.

I also thank the Aub familys publishing agent, Carina Pons, who has shown considerable flexibility with the contract and not a little humor.

And, finally, I thank my dear friends Andy Horton, Win Walker, Clyde Watkins and Manuel Garca Castelln; Andy, because he got me started on the path of film; Win, because she has heard me out many times and given me good advice; Clyde, because he has provided the perspective of an educated nonSpanish speaker when I needed one, and Manolo, who generously answered questions about my translation.

Translators Introduction

When he had corrected the first galley proofs of Cien aos de soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude), Gabriel Garca Mrquez took them with him to a party given by his close friends Luis and Janet Alcoriza, because he wanted to satisfy the insatiable curiosity of the guest of honor, don Luis Buuel. Buuel, Garca Mrquez continues, came up with every imaginable conjecture about the art of correcting, not in order to improve, but to conceal.

Buuel was notorious for feeding the pressand indeed everyone elseversions of his life that were often fanciful, especially regarding any subject he considered touchy. This is particularly true of Mon dernier soupir (My Last Sigh), the often misleading memoir that was actually written by his long-time collaborator Jean-Claude Carrire. In Objects of Desire: Conversations with Luis Buuel, the Mexican filmmakers Jos de la Colina and Toms Prez Turrent admit that the process of the book was a real battle, a constant pursuit of somebody who often came out victorious, hence the title of the Spanish edition: Prohibido asomarse al interior (Forbidden to Look Inside 8).

But Buuel was hard put to deceive Aub, who knew him and his circumstances in ways that few interviewers could claim. They first met in Paris in 1925, later worked together in the embassy of the Spanish Republicwhich, in addition to the usual embassy duties, engaged in a concerted public relations effort for the Republic, and also acted as a center of proRepublican espionageduring the Civil War, and both wound up spending most of their adult lives in Mexico. The many different visions of Buuel provided not only by his friends and relations but also by the filmmaker himself made him a particularly elusive subject, and Aub finally decided that instead of trying to reconcile these different impressions, he would include them allor almost allnot so the reader could choose between them, but to present them all as true, which indeed they are in some sense.

In 1967, Aub was urged to write a book on Buuel by the editors of Aguilar, a major publishing company in Spain. He accepted the charge, and in the late 1960s, he began a series of interviews, not only with Buuel, but also with his family, friends and collaborators. The interviews would take him from Mexico to Spain (which he had not visited since the end of the Civil War), France and Italy. To conduct these interviews, he outfitted himself with an invention that was just taking off in popularity: the cassette recorder.

Thanks, in part, to this mechanism, the book is notable for the presence of so many different voicescaught on tape and later transcribed by the authorthat reach us from different cultures and times, not just because of their memories of early twentieth-century Aragn and Madrid, and of Paris in the twenties and thirties, as well as the U.S. in the forties and Mexico in the forties and fifties, but also their expression of the late sixties and early seventies in these places, voices, primarily of men, with no sense of the politically correct speech that marks so many of our present-day utterances.

In addition to the interviews, Aub also began to collect ancillary material on the filmmaker, other artists and the period. With the passage of time, as he explains in his prologue, his vision of the book developed, and he began to see it as one of his own novels, in some of which apocryphal artists are treated as though they were real, given a body of work, reviews, press releases and so on (most notably in Jusep Torres Campalans), while in others real figures are treated as though they were fictional creations. In all of them, the intent is to portray a period, a place, a movement as well as a personality. This accumulation, Aub writes in his prologue here, can be blamed on a certain waya style, sayof writing books that are neither novels nor biographies, nor chronicles, nor essays, but a combination of all, mixed in with photographs that clarify the text and fragments of other books. I have worked with all this in my effort to discover the

Next page