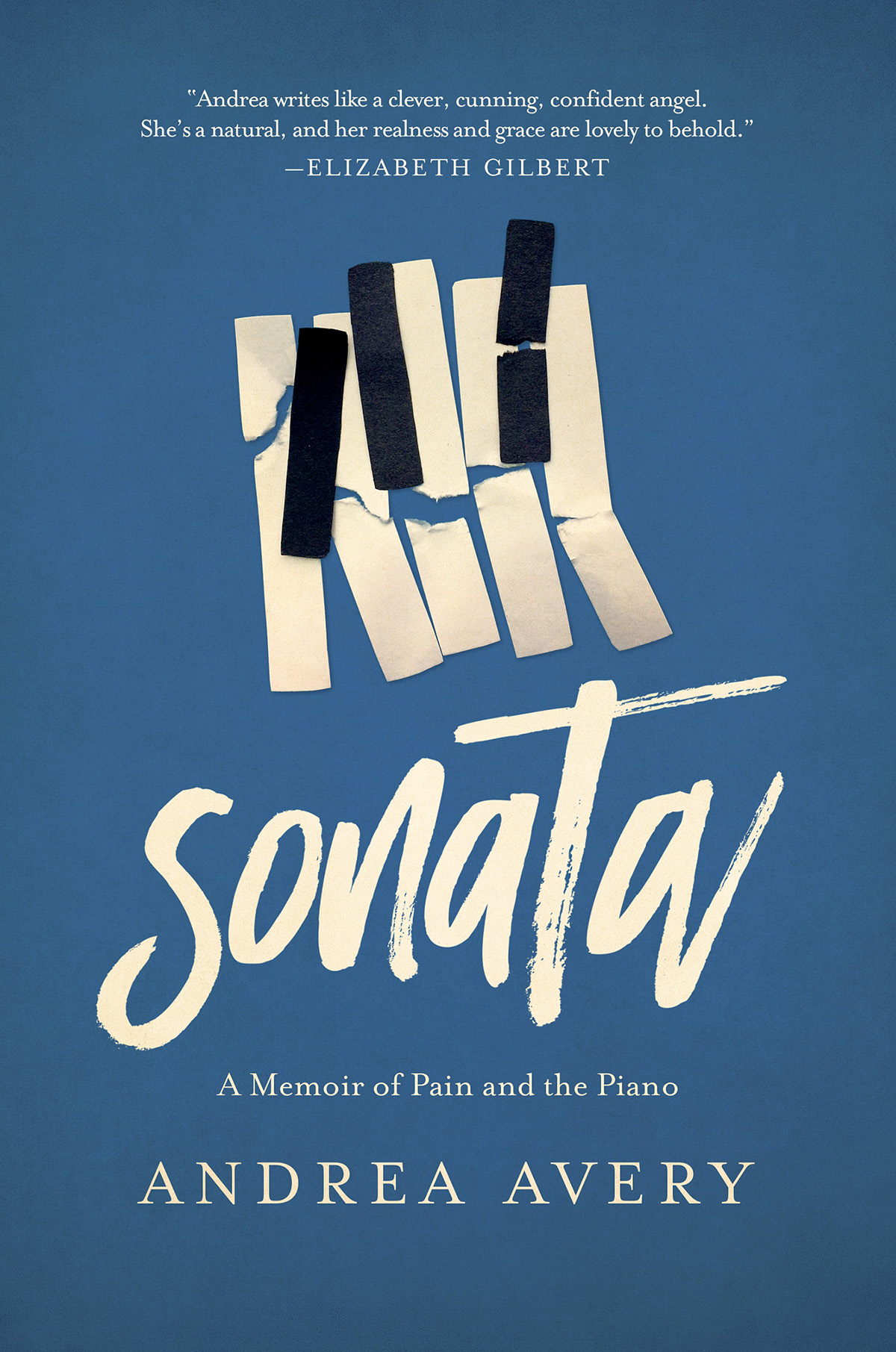

Sonata

A Memoir of Pain and the Piano

ANDREA AVERY

I want to thank everyone at Pegasus Books, especially my editor, Jessica Case, for her intuitive, insightful, expert, and generous work on this book. My work would not have found its way to Jessica were it not for my agent, Rob Kirkpatrick of the Stuart Agency, who brought his own musical and literary brilliance to helping me tell the story I wanted to tell and got it into exactly the right hands. I would like to thank Erica Ferguson for her keen, perceptive, and artful copyediting and Maria Fernandez for her stunning book design.

In seventh grade, my English teacher mentioned she couldnt wait to read the book I wrote someday, a comment that has sustained me for many years. I am happy to finally be turning this in to you, Kay Katz! I am the beneficiary of many other teachers who have shaped my tastes, improved my reading diet, and generously and patiently responded to many thousands of my words. Thank you to Nancy Sullivan, Catherine Hammond, Larry Ellis, and Jacqueline Wheeler. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to the creative writing faculty at Arizona State, many of whom went beyond the role of teacher to become lifelong friends and mentors: Ron Carlson, T.M. McNally, Sally Ball, Jay Boyer, and Alberto Ros. To the music teachers who also nurtured meRon Frezzo, James DeMars, Randall Shinn, Rodney RogersI hope you hear music in this work and know that your efforts were not wasted.

I want to thank Rose Weitz for her steadfast friendship and encouragement, which have buoyed me, and whose invitations to speak at her Womens Studies classes at ASU have allowed me to refine this book as well as my understanding of myself and my body. Thanks, too, to Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and Mary Felstiner for their wisdom and their writing. These women taught me how to pay attention to my experiences in my body and make something beautiful from them. Miriam Savitri Axelrod was a remarkably sensitive and generous reader, and to her I am ever thankful.

Many writers and artists have inspired and encouraged me, taking away from their own precious desk time to read and respond to my work. Thanks to Elizabeth Gilbert, Stacey Richter, Gregory Spatz, Caridwen Irvine-Spatz, Tayari Jones, and Natalie Serber. I am eternally thankful to Squaw Valley Community of Writers for the opportunity to improve my work in a magical setting with gracious and talented writers. Joe Theismann, thank you for a much-needed pep talk and for coaching me to be the quarterback of my life.

I would like to thank my cousin, Peter Torvik, who lent his expertise to the music theory elements of this book, as well as the brilliant and magnanimous music theorist Dr. Joseph Straus specifically for helping me with the music theory and history and more generally for his remarkable work in the intersection of music and disability.

When you are a chronically ill writer, your medical team is part of your writing community. I wish to thank Dr. Donald Sheridan, Dr. Dennis Armstrong, Dr. Dana Seltzer, and Chris Reynolds and Diana Rivera at Desert Hand Therapy. For her crucial early care of me as well as her ongoing support (and for reviewing my writing on rheumatoid arthritis), I owe huge thanks to Dr. Patience White. Thanks, too, to Dr. Gary Hoffman for his expert review and helpful input on my writing about the arthritis disease process, diagnosis, prevalence, and treatment.

The love, support, and patience of my friends, even through my long silences, mean more than they know. Lauren, Davey, Beth, Sarah, Kat, Jen, RB, Betsy, Sharon, Keith, Gabi, Barb, Patrick, Andy, Lisa, Rich, thank you. Marc, thank you (I hope you like the book, and I really hope you like the font). Thank you to my students at Phoenix Country Day School, whose creativity and authenticity inspire meIve been your student all along.

For seeming to intuit when I want to be a chatterbox and when I want to be a recluse, and for rolling with all kinds of punches, I thank my husband, Fred. I love you. Most of all, thank you to my family: Mom, Dad, Erica (not just my sister but the best reader I know), Matthew, Chris. I hope in my version of our story you hear how terribly much I love you. Belonging to our family is the proudest distinction of my life.

For Mom and Dad

Imagine that you were in pain and simultaneously hearing a piano being tuned in the next room. You say, Itll stop soon. It surely makes quite a difference whether you mean the pain or the piano-tuning.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

T here was a painfully short before, and then the rest came after.

The first twelve years of my life, I lived in another body. Those twelve years before 1989 get smaller and smaller in the rearview mirror: They were once all Id known, then the better half, now just a blip. Like matter itself, they will never entirely disappear.

In this before, I was going to be a pianist. I was not crazy to think so. By some magic of genetics and environment, the keys rose to meet my fingers and music came. And then, too soon, by some inverted miracle of genetics and environment, rheumatoid arthritis appeared. The keys still rose to meet my fingers, but my curling fingers recoiled. For too long, I tried to be arthritic and a pianist. For too long, I refused to believe that I could not be both. For decades, with swelling and crumbling hands, I groped at the piano, kneading, fearing that if I lost it, I would lose the only thing I liked about myself. Well into foolish adulthood, music swelled up inside me, infectious, a boil in need of lancing, and I kept one bruised and brutalized hand on the keyboard. With the other hand, I tried to fend off the diseaseas precocious as my musical talent itselfthat threatened to become the most notable thing about me.

These scenes are the notes that spell the chord of me; these are the pitches to which Im tuned. Three notes: one, three, five. Place your hands on the white-topped keys of the pianowrists up, loose, thats goodand play them one by one: first thumb, then middle finger, then pinkie. One, three, five: Wellness, injury, illness. One, three, five. Do, mi, sol.

In musical terms:

ONE (I): This is the tonic, the tonal center, home.

THREE (III): This is the mediant, halfway between the tonic and the dominant.

FIVE (V): This is the dominant, second in importance to the tonic.

One, three, five. Play each note alone, roll the notes like the strings of a harp, or smash your searing hand on them all at once, a virulent virtuoso:

(I)

This is home, the note to which it must all resolve. To be satisfactory, to feel finished, I must get back here.

Its a swampy Maryland summer, 1985. Its hot in my room. I cant sleep. I have the window open. My dad is stingy with the air-conditioning, and my room is full of things that generate their own heat: green pile carpeting and hand-me-down stuffed animals and clothes spilling from closet doors and draped over chair backs. The scalloped edging on the pink-and-white gingham canopy of my bed flutters in the occasional breeze through the window, and the white bedposts gilded with chintzy gold bands sweat when a passing car spotlights them. I can hear the neighbor boy and his buddies in the driveway next door. They laugh and chuck somethingbeer cans?skittering into the bed of a truck. I turn my pillow over. I kick the flimsy plaid bedspread to the floor. I flail and flop and the tips of my hair get stuck in the sweaty creases of my armpits. When you have a house of your own, my dad likes to say, you can run the air-conditioning as much as you damn well please. I am eight. A house of my own is a long way off. Im going to be fever-hot forever. I extend my long, suntanned legs. Reflexively, I deploy the muscles I dont yet know are called

Next page