Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright.

The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property.

If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Running Press, a division of Hachette Book Group.

The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Photo credits can be found and is an extension of the copyright page.

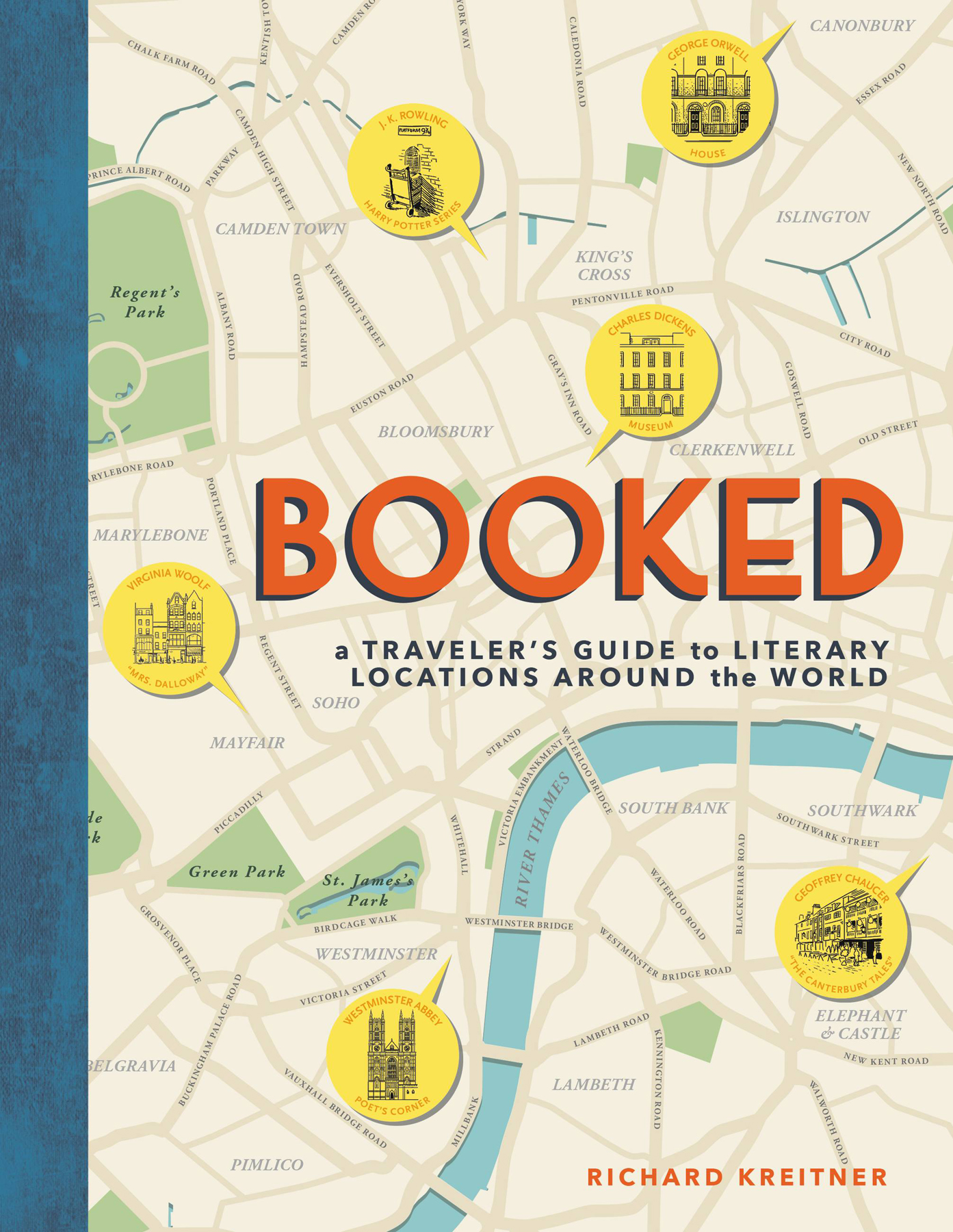

I embarked on my first pilgrimage when I was twenty years old. In frigid, early-winter Montreal, where I was a third-year philosophy student, I struggled to explain to the girl I had just started dating my reasons for going on the trip. She was not convinced. Neither was I. And yet I felt I had to goto find something, as the clich goes, but even more, looking back, to lose something, too.

A week later, there I was: all alone atop a naked rocky peak as dawn lit up a quaint lakeside village far below, snowy mountains shimmering all around me. Shivering with cold, provisioned only with a bar of chocolate, and deliriously happy, I pulled out the book that had brought me there in the first place: a collection of William Wordsworths poetry.

The village at my feet was Grasmere, in the English Lake Districtwhere Wordsworth lived for fifteen years (before moving a few miles down the road), and where he is buried. Once, when he left town for a trip abroad, Wordsworth called Grasmere the loveliest spot that man hath ever found. Looking down at a still, peaceful world cloaked in snowy silence, I fully agreed.

In the year since my first exposure to Wordsworths work, I had read through his poetry over and over, especially The Prelude, his epic autobiographical poem about all the influences that had mysteriously, quietly, and unalterably shaped who and what he became. I was transfixed by its language and consoled by its assurances that nothing is really lost, everything counts, and all will be fine in the end. Like many twenty-year-olds, I thought what Wordsworth calls the terrors, pains, and early miseries of young adulthood would last forever. Who was I, and what would I become? Wordsworth promised the hidden workings of nature itself would see that these burning questions resolved themselves.

None of this, of course, explains why I went to Grasmere. I suppose I wanted to see the influences and impressions that had shaped Wordsworththe peaks and valleys he explored as a boy, the meandering river that taught him constancy and change, the lakeside patch of thousands of daffodils he thought fondly of in vacant or in pensive moodand, if only for a week, to make them my own.

The Vale of Grasmere in the English District.

Yet despite the exhilarating sunrise walk to the top of Helm Crag, the rocky peak jutting out over Grasmere, the terrors, pains, and miseries that had plagued me in Montreal seemed to have hitched a ride in my knapsack. Those days were a roller coaster of the highest highs and the lowest lows. As I sipped hand-pulled pints at the local pub, walked the fells (as locals call the districts barren hills), toured Wordsworths famous Dove Cottage (which, incredibly to me, still had his two-hundred-year-old mirror), and sipped a few more pints, I struggled with the gnawing fear that I was somehow doing it wrong, that I wasnt communing as fully or as deeply as I should have been with Wordsworth, or Grasmere, or the fells.

I should have trusted Wordsworth more. In hindsight, I see the trip was a turning point. I came back differenta little calmer, stronger, more worthy of myself, as The Prelude puts it.

In the decade since, I have spent much of my spare time making similar trips to places featured in some of my favorite books: poetry and prose, fictional or otherwise. Only now I am not alone. The girlfriend I left behind in Montreala fellow editor at the student newspaperhas since become my wife. She enjoys visiting authors homes and other literary places at least as much as I do and has gamely consented to book-based excursions through the United States and around the world, from New Hampshire and Colorado to Poland and Greece. (Without her intelligence, indulgence, and Harry Potter expertise, this book, and everything else I have done, would have been impossible.)

Why do we search out places from literature? Most obviously it is to see how our mental image of it, shaped by the authors descriptions, matches up with reality. In our minds eye, we map our conception of the place as it is described in the book onto what we see before us, and tally up how much is the same and how much is different, and of that which is different, how so.

Yet when we search out places from books, we are not simply looking for particular buildings or vistas or even atmospheres that made it into the work. There is something weirder and more magical going on. We want to see how the artist has transformed banal reality into the stuff of art. There is something even a little religious about itthus the aptness of the word pilgrimage.

When we travel to places featured in books we love, we are not only looking for how the place has impacted the book but how the book has impacted the place. After devouring a work that seems as if made only for us, it can be thrilling to see the fictional world so fully imagined in our minds recreated and saluted in this, the physical worldas in a statue of one of the characters (like that depicting Ignatius J. Reilly, from John Kennedy Tooles