CONTENTS

Guide

Ghost Empire

A brilliant reconstruction of the saga of power, glory, invasion and decay that is the one-thousand year story of Constantinople. A truly marvellous book. Simon Winchester

Saga Land (co-authored with Kri Gslason)

I adored this book a wondrous compendium of Icelands best sagas. Hannah Kent

To the students of 1989

The truth will prevail.

Jan Hus, fifteenth-century Bohemian religious reformer, burnt at the stake

It was my belief that the truth would prevail, but I did not expect it to prevail unaided.

Edvard Benes, second president of Czechoslovakia, exiled after the Nazi occupation

The truth prevails, but its hard work.

Jan Masaryk, Czechoslovak foreign minister, found dead in 1948 in the courtyard below his bathroom window

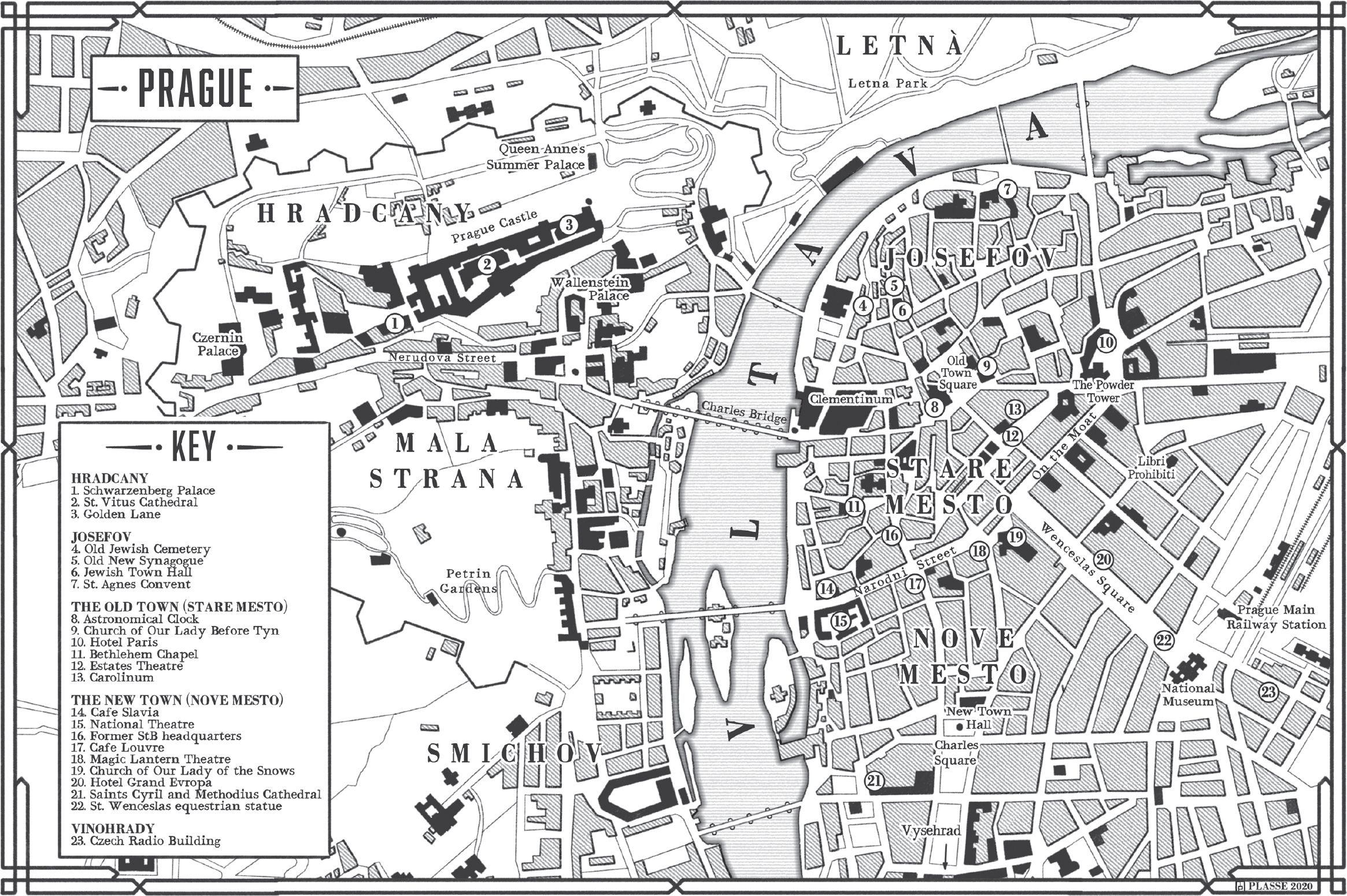

Maxime Plasse

The author

CONTENTS

S OMEWHERE BEYOND THE orbit of Mars, among the countless boulders, and planetoids of the asteroid belt, lies a rock, around 70 kilometres wide, known by astronomers as 264 Libussa. The asteroid was named after the legendary witch queen of Bohemia, who was said to have founded the city of Prague.

Libussa, according to the legend, was uncommonly wise and blessed with the gift of prophecy. Her exploits were first recorded in a chronicle written a thousand years ago. Queen Libussa, it was said, stood on the edge of a steep cliff one day, looking down at the Vltava River and the forest beyond, when her attendants saw that her breath was short and that her eyes had become strange and dreamy. Stretching her arms towards the wilderness, Libussa gave voice to the prophecy welling up from within: I see a great city. Its glory will touch the stars.

Turning to her attendants, she said, In the forest below there is a clearing. There you will find a man making the best use of his teeth at midday. That is the place where this city will be founded.

The courtiers went down into the valley, and in a clearing they found some men in the process of building a house. It was midday and so they were eating their lunch. One of the men, however, was still at work, sawing a block of wood.

The courtiers had found their man.

What are you making? they asked.

A threshold, he replied. A threshold for a house, a prah in the Czech language.

Which is how the city that grew up there came to be known as Praha, Prag or Prague.

A THRESHOLD, in a childrens tale, is a device that serves as a point of transition from the everyday world into the dream realm. Ideally, its a commonplace object: a looking-glass, a wardrobe in an attic, a broken gate at the bottom of a meadow. So many visitors to Prague over the centuries have noticed this uneasy liminal quality; the uncanny stillness of the streets on a winters night can make the waking world appear thin and diaphanous. Even the drab Soviet-era apartment blocks of Prague can seem airless and haunted.

Patrick Leigh Fermor, who came in the early 1930s, was unsettled by Pragues strangeness: There were moments, he wrote, when every detail seemed the tip of a phalanx of inexplicable phantoms. Troubling creatures that haunt the worlds imagination have found their way across Pragues threshold: a golem made from river mud, a human transformed into a cockroach, a factory-made humanoid. An easy ten-minute walk through the city can take you from a clock that runs backwards to another where the skeleton of Death chimes the hour every hour; along the way you pass through squares once splashed with the blood of heretics, houses where alchemists attempted to transmute base matter into gold, and churches strafed with Nazi bullets.

Those who come to Prague from New-World metropolises like Sydney, Toronto or Los Angeles are sometimes touched by an odd sense of dj vu, a vague impression of homecoming that can eventually be located in our memories of the old European folk tales given to us as children. But Pragues imaginative landscape is no Disneyland; its the natural home of the older, more troubling versions of those tales, where Cinderellas step-sisters lop off parts of their feet to fit the glass slipper, and Little Red Riding Hood is compelled to dance naked for the wolf before it eats her alive.

Andre Breton, high priest of the Surrealist movement, was given a heros welcome when he came to Prague in 1935. Walking the streets, he instantly grasped that Pragues surrealist masterpiece was the city itself, a colossal work of automatic writing, scribbled over time from some collective subconscious impulse. Prague was, he said, one of those cities that effectively pin down poetic thought, which is always more or less adrift in space... When viewed from a distance, with her towers that bristle like no others, it seems to me to be the magic capital of old Europe.

Keyholes are glittering in the sky, wrote Pragues most lyrical poet Jaroslav Seifert,

and when a cloud covers them

somebodys hand is on the door-knob

and the eye, which had hoped to see a mystery,

gazes in vain.

I wouldnt mind opening that door,

except I dont know which,

and then I fear what I might find.

THE ORIGINS OF THIS BOOK can be traced to the Velvet Revolution, when I found myself among the happiest people in Europe, revelling in the peaceful overthrow of a decrepit police state. It was one of the most exciting moments of my life. At the time, I knew something of Pragues twentieth-century history: enough to feel a shiver of dread as I passed by the secret police headquarters on Bartolomejska Street, but the origins of the city itself were a mystery to me. Prague in those days was grimy and tendril-like, it seemed that no human hand had been needed to construct it; that it had somehow risen up from the soil like a stone garden, summoned by Libussas chthonic spell:

Next page