Many years later, when John Jagamarra had grown to be a man and had a son of his own, they went back to Dryborough Station.

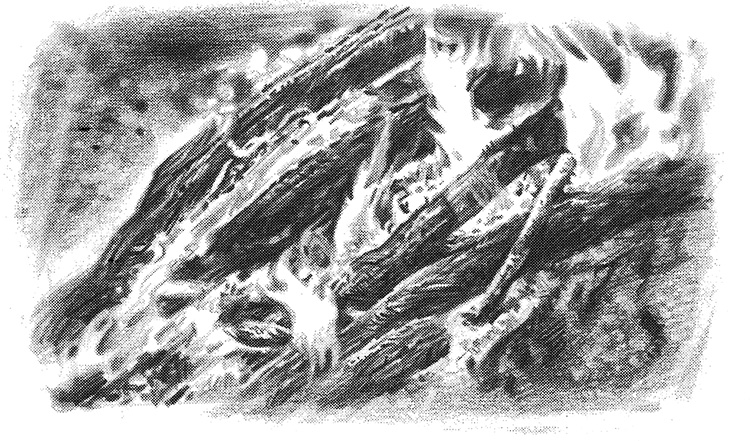

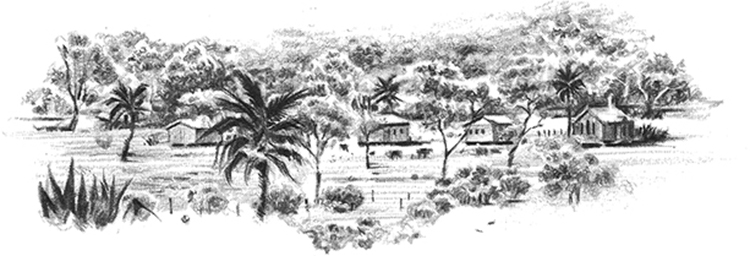

The place had long since been abandoned to the drought. The homestead was deserted. The stockyards were falling down and the waterhole was dry. And down the overgrown track, only a few sheets of rusting tin were left to show there had once been a camp under the acacia trees.

There was no one to tell them where the people had gone, or to say what had happened.

John Jagamarra camped under the trees and lit his fire where it had always been. He sang softly to himself and his son, trying to remember the words and their meanings that Jabal had used. Remembering the story of Crow and the Eagle. Remembering the pain that lived inside him, and the sight of Liyan sprawled in the weeping dust. Telling these things to his boy.

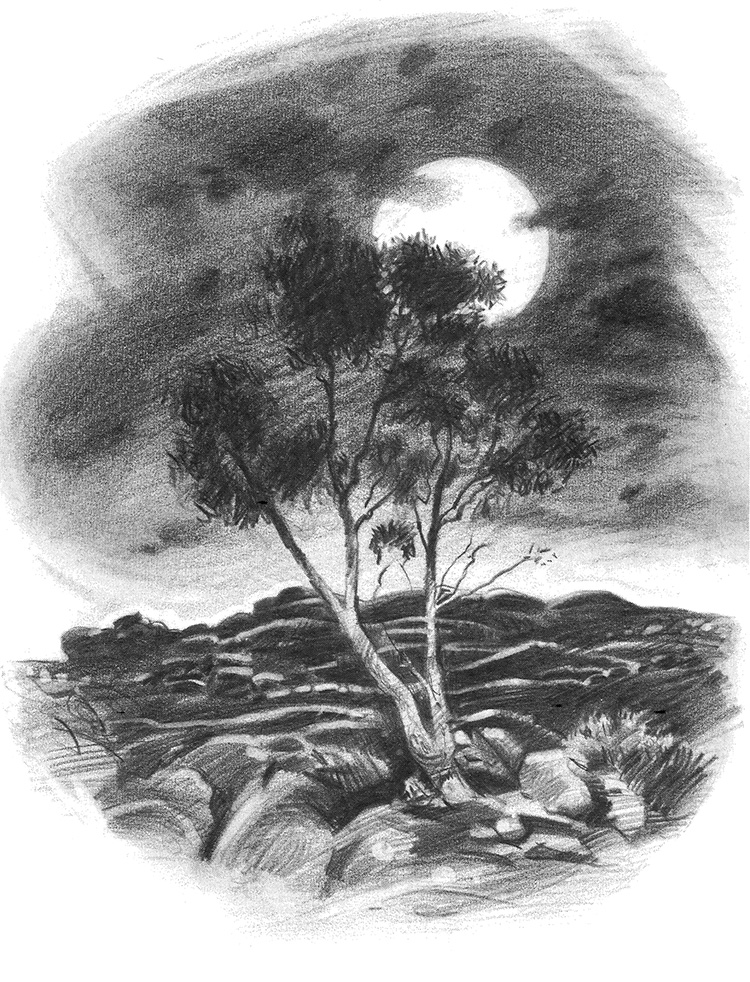

That night, under the watching eyes of the stars, among the Ancestral spirits of the ancient land, John Jagamarra knew that he would look for his mother and those people to whom he belonged and would keep on looking for them until they were found, no matter how many years it took.

And in the morning before they left, John Jagamarra gathered a handful of ashes and black charcoal from the fire, and rubbed it into his skin and the flesh of his young son. He rubbed it in as deep as he could, so that it might become part of them and never wash out again. Not now. Not so long as they lived.

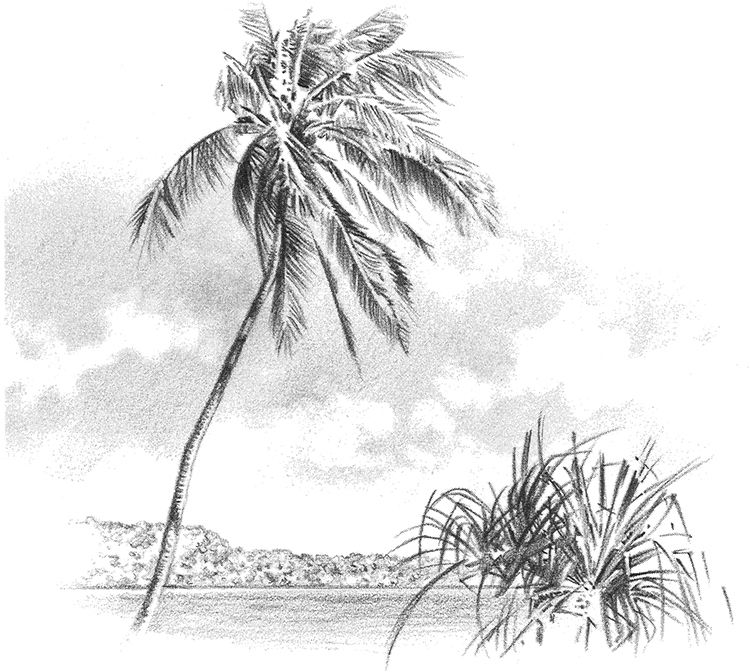

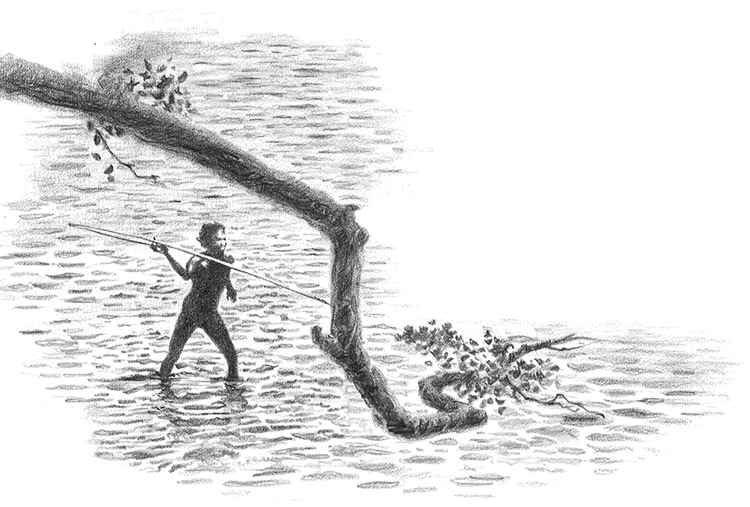

John Jagamarra grew up at the Pearl Bay Mission for Aboriginal Children by the coast in the far north-west. It was a very beautiful place. The palm trees and the scented vines grew down to the slow green tropical sea, where they used to fish and dive for trochus shells. But it was not home.

The Mission had been built many years ago by the Fathers. Mostly they were good men. They built a stone church with a bell tower and narrow windows with yellow glass that they remembered from their own country on the other side of the world. They read from the Bible of a loving God, and sang the Latin Mass every Sunday, the Aboriginal altar boys in white surplices.

The Fathers built a school of corrugated iron painted grey, with sleeping huts (four boys or girls to a room) and outhouses the dairy, bakery, and machinery shed. They planted a vegetable garden that grew almost anything beans and peanuts and ripe crimson watermelons and an orchard heavy with fruit mangoes and pawpaws and sweet bananas.

They taught the Aboriginal children how to read and write in English; how to add up and subtract, and how to recite the catechism. They taught them how to grow crops; how to thresh the rice at harvest; how to bake bread, and how to milk the goats.

They taught the girls how to cook and to sew cotton dresses, and the boys, like John Jagamarra, how to make bricks in the kiln, how to plane wood and to make things in the carpenters shop. Still, it was not like home.

For the Fathers did not teach the children the songs, the dancing and the picture making of their own people. They did not speak to them, as their families did, in the Aboriginal tongues, or tell them the stories of the Dreaming and the Ancestor spirits of the land that once had been told around the campfires. They did not show them how to follow the kangaroo through the bush, or how to make spears, or how to find where the wild yams grew. These things the Fathers did not know. Because the Fathers did not know them, they were not allowed. And because they were not allowed, as the years went by, most people forgot them.

No, it was not like home.

It was not like home because very few of the children had been born at Pearl Bay Mission. Nor were their families there, and they rarely came to visit. It was a long way, and often they were not permitted. Most of the children, like John Jagamarra, had been taken from their mothers when they were very young, and sent by the Government men from the Welfare Department to the Fathers at places like Pearl Bay. It was the law of the white people at the time, though it is different now.

The Welfare said it was for the childrens own good. After all, their fathers were generally white men sometimes stockmen, or cooks, or overseers on the cattle stations of the inland. It was felt to be best if those children with the light-coloured skin were sent to be taught in the white mans way.

Nobody asked the mothers before they took the children. Even if they had, it would have made no difference. The Welfare believed they would soon get over their loss. And nobody asked the children they would soon forget. Yet John Jagamarra did not forget. He was nearly five when the Big Man from Welfare came looking for him and you can remember many things when you are almost five years old.

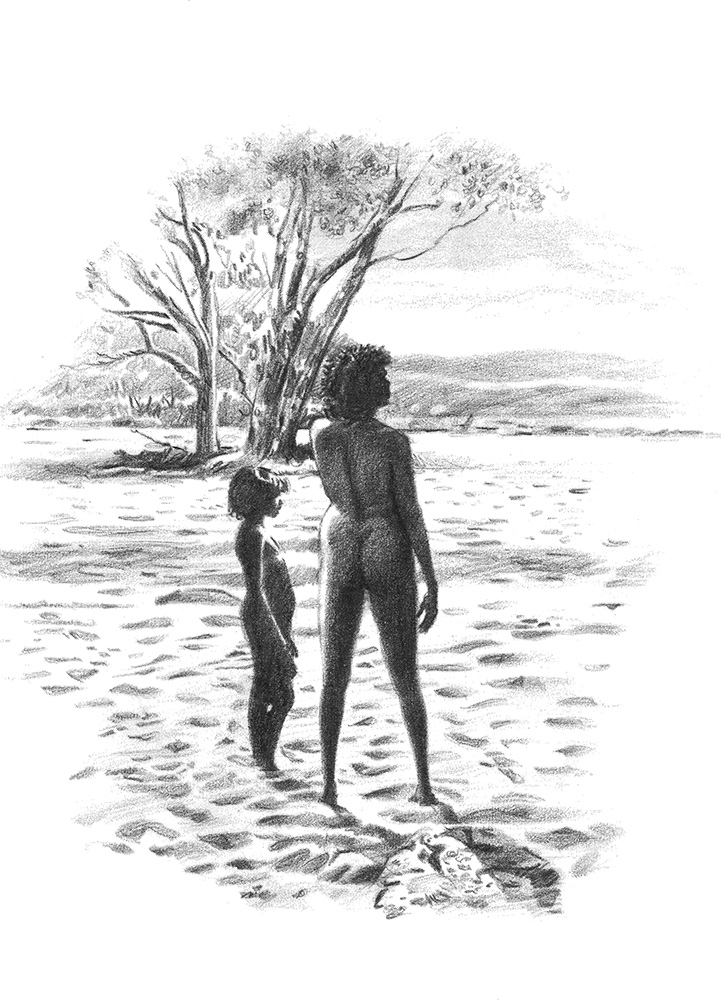

Growing up by the pearl shining sea, John Jagamarra remembered the heat and the dust, the low scrub and the red horizons of the inland desert country near Dryborough Station where he had been born. He remembered the pool in the creek bed where he and the others would swim naked after rain, and the flat lizard rock where they would lie afterwards, sunning themselves.

Sitting through the long afternoons in the schoolroom, sweaty in the shirts and trousers the Fathers said the boys must wear (though mercifully never shoes), John Jagamarra would remember the camp under the acacia trees, just down the track from the station homestead. He would remember the dogs stretched asleep in the shade, pink tongues hanging out; the sounds of women talking beneath the tin and bough shelters; and the sharp cries of excitement when the men rode in on their horses from a day mustering the long-horned cattle.

But it was at night, lying awake and lonely in his narrow iron bed at the Mission, that he could remember things most clearly. It was then that he could feel the cool desert night embracing him, folded in his mothers arms by the campfire after they had eaten lying there contented, half asleep, sensing her presence and the touch of her skin, the colour of evening, so much darker than his own.