Praise for

THE ISLAND OF LOST MAPS

A magical, endlessly engrossing map of a world most of us probably have thought fusty and uninteresting

CHICAGO SUN-TIMES

Elegantly written Miles Harvey has cleverly tapped into our collective fascination with maps and produced a quirky chronicle of cartographical development disguised as a literary crime story

DAILY TELEGRAPH

An all-consuming read that is impossible to put down.

BOOKLIST

A terrific look into one of the worlds million startling subcultures.

NEWSDAY

Harveys first book [is] as entertaining as the most fancifully illustrated old map you could find.

SAN FRANCISCO magazine

The Island of Lost Maps is a treat. It is part history, part detective story and part journey of self-discovery all rolled into one. The scholarship behind the work is exemplary, and the presentation a joy.

FORT WORTH STAR-TELEGRAM

A hardcover edition of this book was originally published in 2000 by Random House. It is here reprinted by arrangement with Random House.

THE ISLAND OF LOST MAPS . Copyright 2000 by Miles Harvey. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information, address: Random House, A Division of Random House, Inc., 299 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10171.

BROADWAY BOOKS and its logo, a letter B bisected on the diagonal, are trademarks of Broadway Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

owing to limitations of space, acknowledgments of permission to quote from unpublished and previously published materials will be found following the Index.

First Broadway Books trade paperback edition published 2001.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Random House edition as follows:

Harvey, Miles

The island of lost maps: a true story of cartographic crime / Miles Harvey.

p. cm.

1. LibrariesUnited StatesSpecial collectionsMapsHistory20th century. 2. Map theftsUnited StatesHistory20th Century. I. Bland,

Gilbert Joseph. II. Title.

Z702.H37 2000

025.82dc21 00-025604

eISBN: 978-0-307-76656-4

v3.1

T O B OB, T INKER, AND M ATTHEW

THE MAPS

T O R ENGIN AND A ZIZE

THE DESTINATIONS

I T IS NOT DOWN IN ANY MAP;

TRUE PLACES NEVER ARE.

HERMAN MELVILLE,

Moby-Dick

Contents

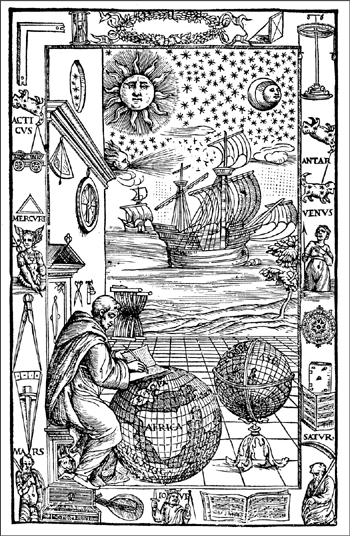

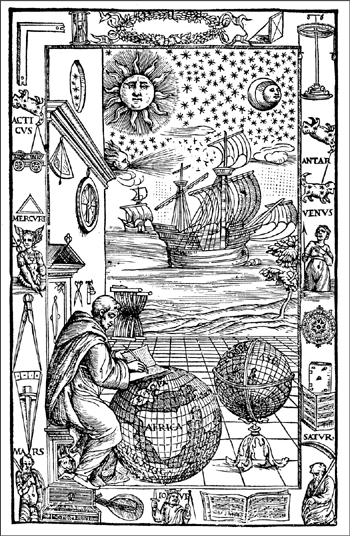

A PRINT FROM A 1537 EDITION OF A WORK BY THE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY GEOGRAPHER JOHANNES DE SACROBOSCO.

INTRODUCTION

Strange Waters

E XPLORERS PIN MAPS TO THEIR WALLS ; journalists tape stories to theirs. For both, doing so is a way of getting their bearings. As I sit down to write this book, the wall behind my computer is unadorned except for two photocopied articles, each of which helps me set the course for the journey ahead. The first one, which I ponder now while sipping coffee, is from a reference book called Who Was Who in World Exploration:

HOUTMAN, CORNELIUS (Cornelis de Houtman) (ca. 15401599).and his brother attempted to acquire classified Portuguese navigational charts detailing the sailing routes to the Indies. They were arrested and briefly held in a Portuguese jail when they were caught trying to smuggle the charts back to Holland.

The coffee I am drinking comes from a Chicago establishment called the Kopi caf, a place where my life was transformed one day and this book was born. As it happens, the story of how the Houtman brothers wound up in jail is also the story of how the Kopi got its name. That, however, is not the primary reason this article hangs on my wall. I keep it there to serve as a constant reminder of the extraordinary power of mapsand the lengths to which human beings will go in obtaining them.

Shakespeare once used the term mappery to describe the passionate study of a map or chart. I am neither a map scholar nor a map collector, but if theres one thing I should make clear about myself from the start its that I am an incorrigible mapperist, an ecstatic contemplator of things cartographic. On the desk in front of me now, in fact, is a reproduction of a very old and very famous map, one that, among other things, shows why the Houtman brothers felt compelled to spy on Portugal.

Published in 1569 by Gerard Mercatorthe greatest cartographer of his era and a Dutch contemporary of the Houtmansit was the first map to use a revolutionary system for projecting the three-dimensional world onto a flat plane. More than four hundred years later, this system is still in such common use that when most of us close our eyes and imagine a map of the world, we are seeing Mercators rendition of the Earth. But for all the works towering achievements, what I notice at first glance are its mistakes and misconceptions, its whimsies and wild stabs in the dark.

Gazing at Mercators chart, I see a planet strikingly different from our own, a world full of blank spaces and never-never lands. North America turns into an amorphous blob that reaches so far west it is almost joined to Asia at the hip. South America has an unaccountable protrusion from its southwestern shores, a topographic tail feather that makes the continent look something like a giant waterfowl. This beast is, in turn, perched upon a very peculiar nesta huge polar landmass, many times the size of present-day Antarctica. Known as the Great Southern Continent or the Unknown Southern Land (or, to more optimistic cartographers, the Country Not Yet Discovered), it was a place ancient geographers had dreamed up to complement their belief that the Earth was perfectly symmetrical. The Arctic region, meanwhile, is a massive donut of land, broken up by four rivers that lead into a polar ocean, through which water was thought to flow to the center of the Earth. From this strange sea rises a giant magnetic black rock, which, according to ancient versions of the myth, destroyed ships by pulling out the nails that held them together.

It is easy, with centuries of hindsight, to chuckle at such notions. But for people like Mercator and the Houtmans the stillhazy outlines of the world were no laughing matter. Having refrained from widespread ocean exploration until the fifteenth century, Renaissance Europe was in a high-stakes rush to make up for lost time. Portugal had led the charge. Beginning in around 1420 under the direction of a prince who would be dubbed Henry the Navigator by later generations, the Portuguese launched a series of explorations down the west coast of Africa. Bartolomeu Dias arrived at what we now call the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, and ten years later Vasco da Gama became the first European to travel to India by sea. In so doing, he helped establish a Portuguese economic empire in the Far East, the realm of pepper, spices, drugs, pearls, and silk.

The Portuguese controlled the Indies because the Portuguese controlled the maps. Attempting to establish and preserve a trade monopoly, Henry the Navigator and his successors guarded their navigational secrets with an iron hand. No foreign ship was allowed to sail to the Indies, wrote the historian George Masselman. The penalty was confiscation of the ship and committal of the crew to a lifetime in the galleys. Nor were maps allowed to circulate. When Pedro lvares Cabral returned from India in 1501ending a trip in which he became, according to some scholars, the first European to sight Brazilan Italian agent complained, It is impossible to get a chart of the voyage, because the [Portuguese] King has decreed the death penalty for anyone sending one abroad.