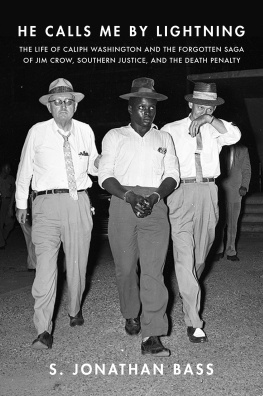

ALSO BY S. JONATHAN BASS

Blessed Are the Peacemakers: Martin Luther King, Jr.,

Eight White Religious Leaders, and the

Letter from Birmingham Jail

For Kathleen, Caroline, and Nathaniel

Copyright 2017 by S. Jonathan Bass

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Ellen Cipriano

Production manager: Anna Oler

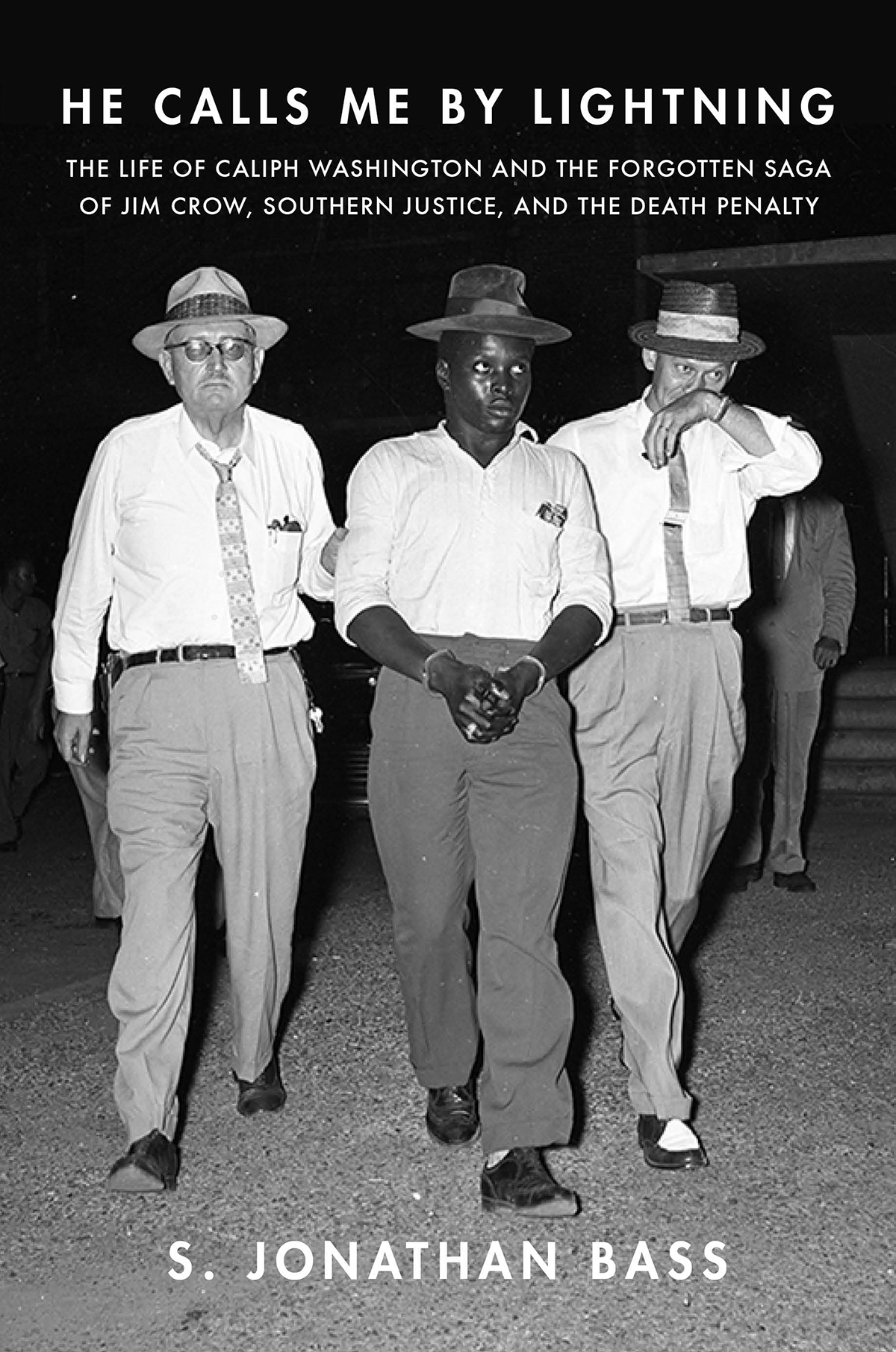

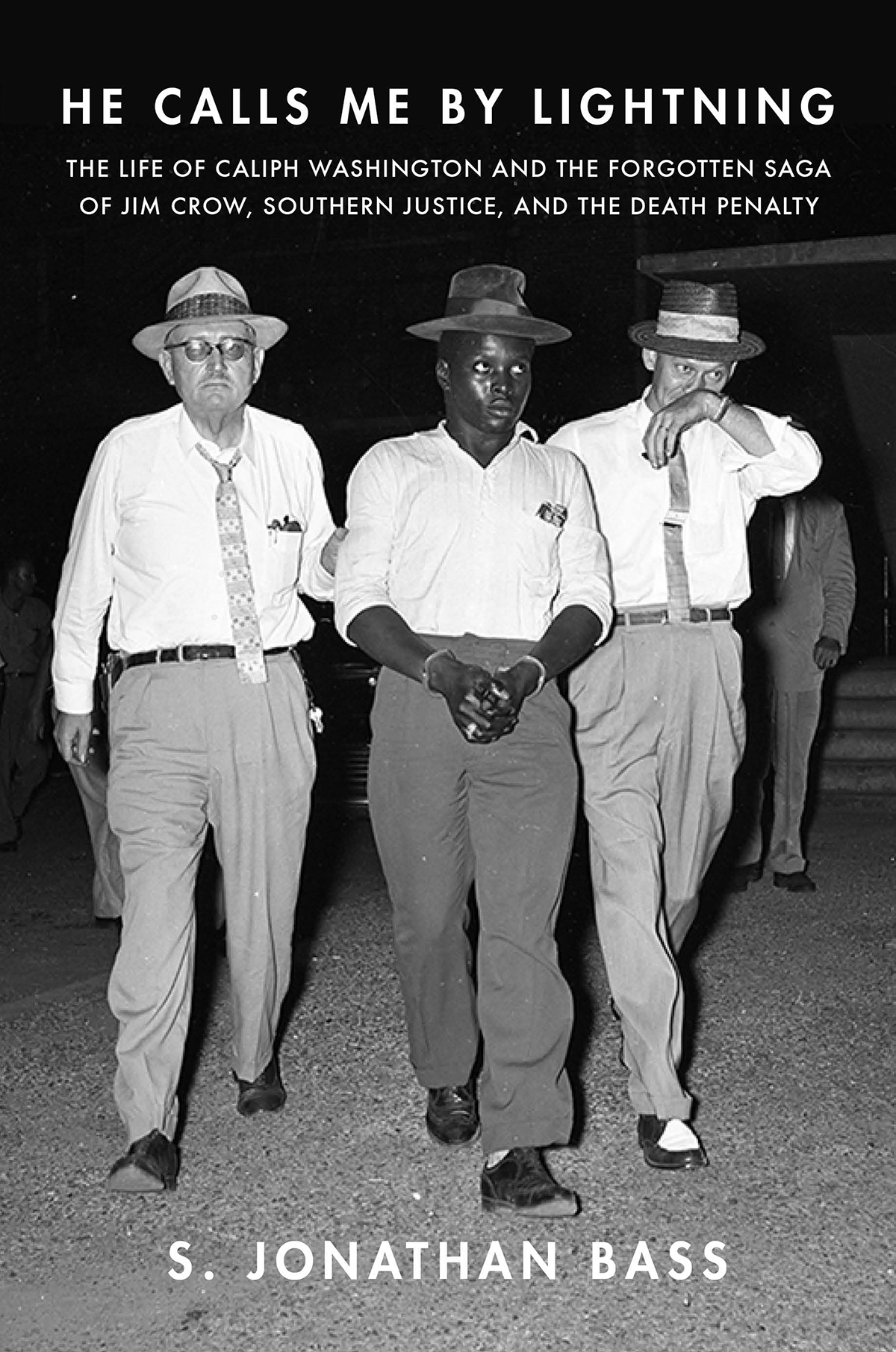

Jacket Photographs: The Birmingham News Archive / Advance

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Bass, S. Jonathan, author.

Title: He calls me by lightning : the life of Caliph Washington and the forgotten

saga of Jim Crow, southern justice, and the death penalty / S. Jonathan Bass.

Description: First edition. | New York ; London : Liveright Publishing Corporation,

[2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005135 | ISBN 9781631492372 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Washington, Caliph, 19392001. | Discrimination in

criminal justice administrationAlabamaHistory. | African American prisoners

AlabamaBiography. | Death row inmatesAlabamaBiography. |

AlabamaRace relationsHistory.

Classification: LCC E185.93.A3 B37 2017 | DDC 305.8009761dc23 LC record

available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005135

ISBN 978-1-63149-238-9 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

CONTENTS

For hardship does not spring from the soil, nor does trouble sprout from the ground.

JOB 5:6

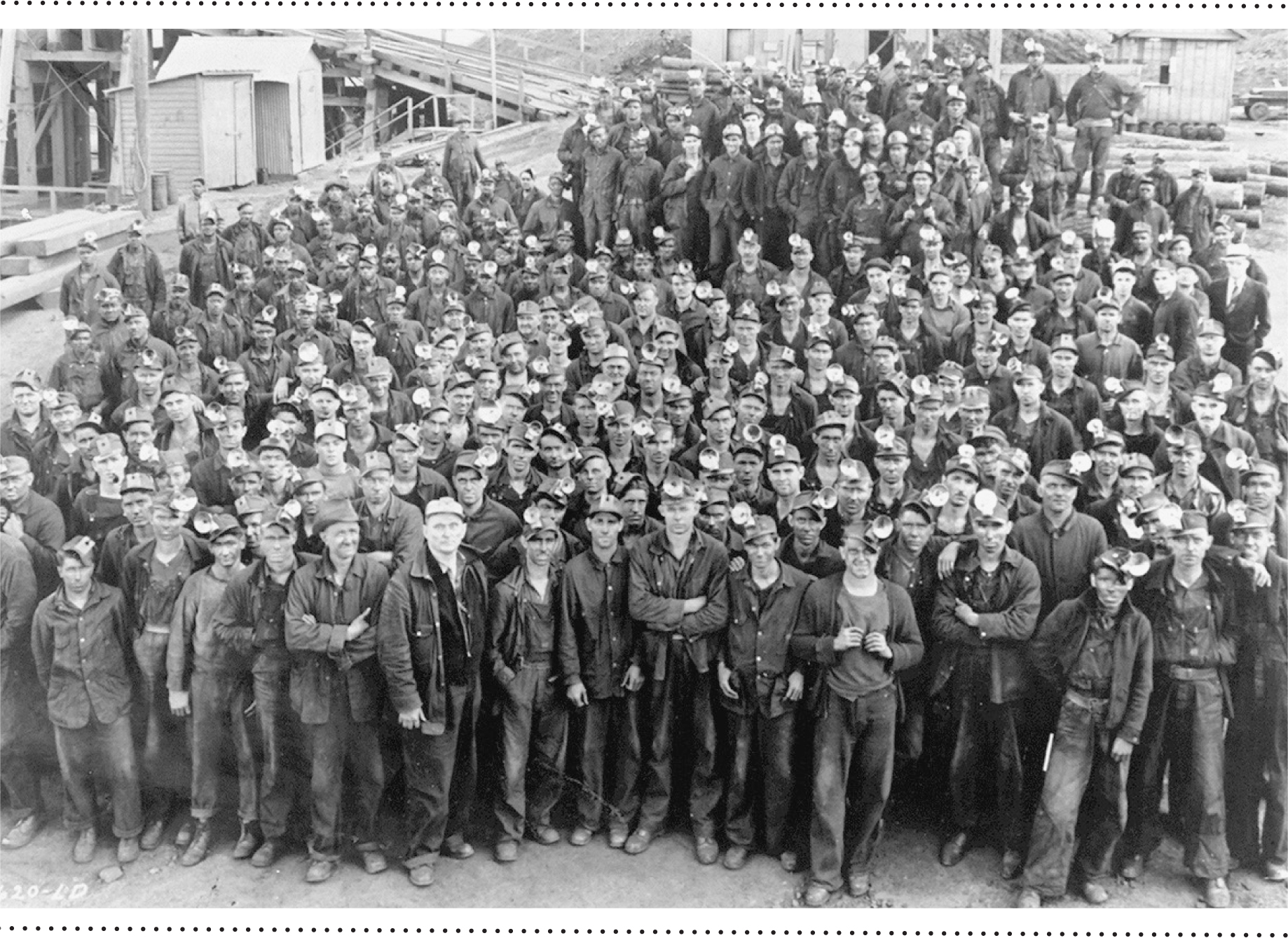

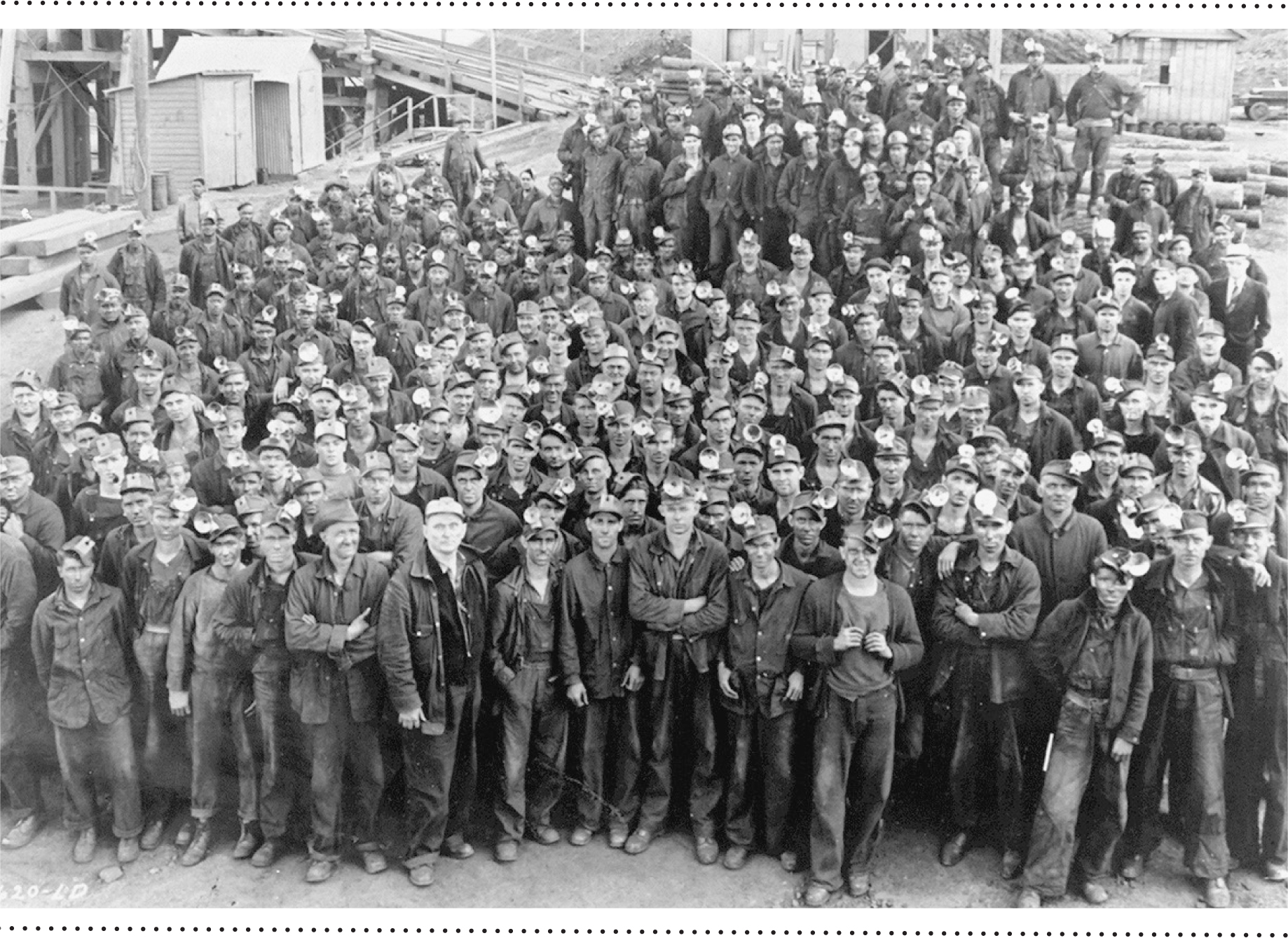

Muscoda Iron Ore miners in the early 1940s.

S HE WAS ALREADY lying in a coffin in the Bessemer Public Library the first time I saw Hazel Farris. I was on an elementary school field trip to see Bessemer, Alabamas most celebrated citizen: a leathery corpse known as Hazel the Mummy. When we arrived at the citys library, located in the majestic old post office building on Nineteenth Street, our hosts ushered us down the stairs to the basement and a makeshift hall of history where Hazel was lying in state. Never before had I seen a dead body, much less one that passed on over seventy years earlier. As I gazed upon this grotesque artifactfaded ruddy hair, hollow eye sockets, sunken cheekbones, and broken and missing teethmy thoughts were a mixture of horror and fascination. Her skin looked like an overcooked Idaho potato, and every joint, rib, and bone was visible underneath.

Decades later, when I came across an old promotional poster for Ms. Farris, her image came rushing back, as did the lore surrounding her death. According to the story, she was a pint-sized, red-headed woman in Louisville, Kentucky, who possessed a fierce temper, drank whiskey straight from the bottle, and fought with her husband. At breakfast on the morning of August 16, 1905, she announced her intention to buy a new hat. When her husband objected to this latest spending spree, she pulled a six-gun and shot him dead. As she stood over her spouses lifeless corpse and inspected the deed she had done, three city policemen rushed through the door. Farris turned and fired three more shotskilling each officer. Within minutes, a county sheriffs deputy arrived and slipped into the house. He saw the bodies littered across the floor, and as he tried to sneak up behind Hazel, she turned suddenly, and the pair tussled over the deputys gun. His gun discharged, and a wayward bullet tore off Hazels ring finger. She soon broke free from his grip, grabbed her pistol from the floor, and ended his life with a single shot.

Hazel Farris fled Kentucky and took refuge among the thieves, murderers, and whores living at the turn of the century in the wild young town of Bessemer, Alabama. She found work in a bordello in the red-light district and a new lovea police officer. It was short-lived, however. When she entrusted her cop-killing stories to her policeman, he opted for the $500 bounty on her head as opposed to her love. Rather than face the hangmans noose, Farris ended her life with a heady mixture of arsenic and whiskey on December 20, 1906. Her corpse was taken to a local furniture store, where it mummified and was later sold to a carnival show barker.

For over a hundred years, Bessemer residents recounted this sordid tale of Hazel Farris. Few locals, however, asked why a prostitute who murdered five men and took her own life was the citys most revered and celebrated citizen. The answer was undeniably obvious, even if it was lost upon the citys white residents: Hazel the Mummy was an all-too-fitting symbol of Bessemera small industrial town divided by race, labor, and ideologywhere an incendiary brew of vice, violence, and corruption thrived. This was a city that counted among its population Communists, vigilantes, black revolutionaries, union thugs, pathological racists, scabs, mobsters, and criminalsall of whom used violence as a necessity to gain or maintain power. And this was a place where crooked politicians and lawless policemen lined their pockets with money and sin, where vice was plentiful and virtue was lacking, where murder and mayhem were essential elements of the culture, and where poor, itinerant individuals like Hazel Farris looked to escape lifes sorrows in a city of strangers.

During the already fractious summer of 1957, fifty years after Hazels death, another downhearted resident searched for a way out of Bessemer. His name, unknown to history, was Caliph Washington. Just seventeen, he was the prime suspect in the shooting death of a policeman, James B. Cowboy Clark. The racial element to the apparent murderWashington was black; Clark was whitefueled the sweltering fury of Bessemers all-white police force. Most of the citys population was black, and race only intensified an already omnipresent feeling of danger as the lawmen hunted mercilessly for young Washington. Alone and abandoned, he hid in the woods and prayed for escape.

I first heard of Caliph Washingtons story from David Murphy, who brought a copy of an old handbill to my office at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama, and smacked it on top of my desk. Youve got to read this, he proclaimed. Murphy, then an undergraduate, was working on his research project for my civil rights history class. In a packet of materials he received from a far-away archive of the Roman Catholic Josephites was a leaflet entitled Wrongly Condemned Man Held Without Trial. The man was Caliph Washington. As I soon appreciated, it was indeed a great untold story, but there were, of course, plenty of forgotten tales from the civil rights era that needed telling. I slipped the article into a future projects folder and hoped, perhaps, that I would look at it again someday. Someday, however, came sooner than I expected.

One morning as I visited with Reverend Wilson Fallin, a Baptist pastor, historian, and Bessemer native, I asked if he had known Caliph Washington. In his rich, sonorous voice, he answered, Oh yes, and proceeded to give me a soul-stirring sermon on Caliph Washington. The minister had known him well and encouraged me to dig a little deeper into his tragic experiences. A few days later, Dr. Fallin spoke at St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Church in Bessemer, and afterward a small woman walked up to him and said, You probably dont remember me, but my husbands name was Caliph. Wilson responded, Of course I remember you, and I know someone that you need to talk to. The next day I received a message to call Mrs. Washington.

Next page