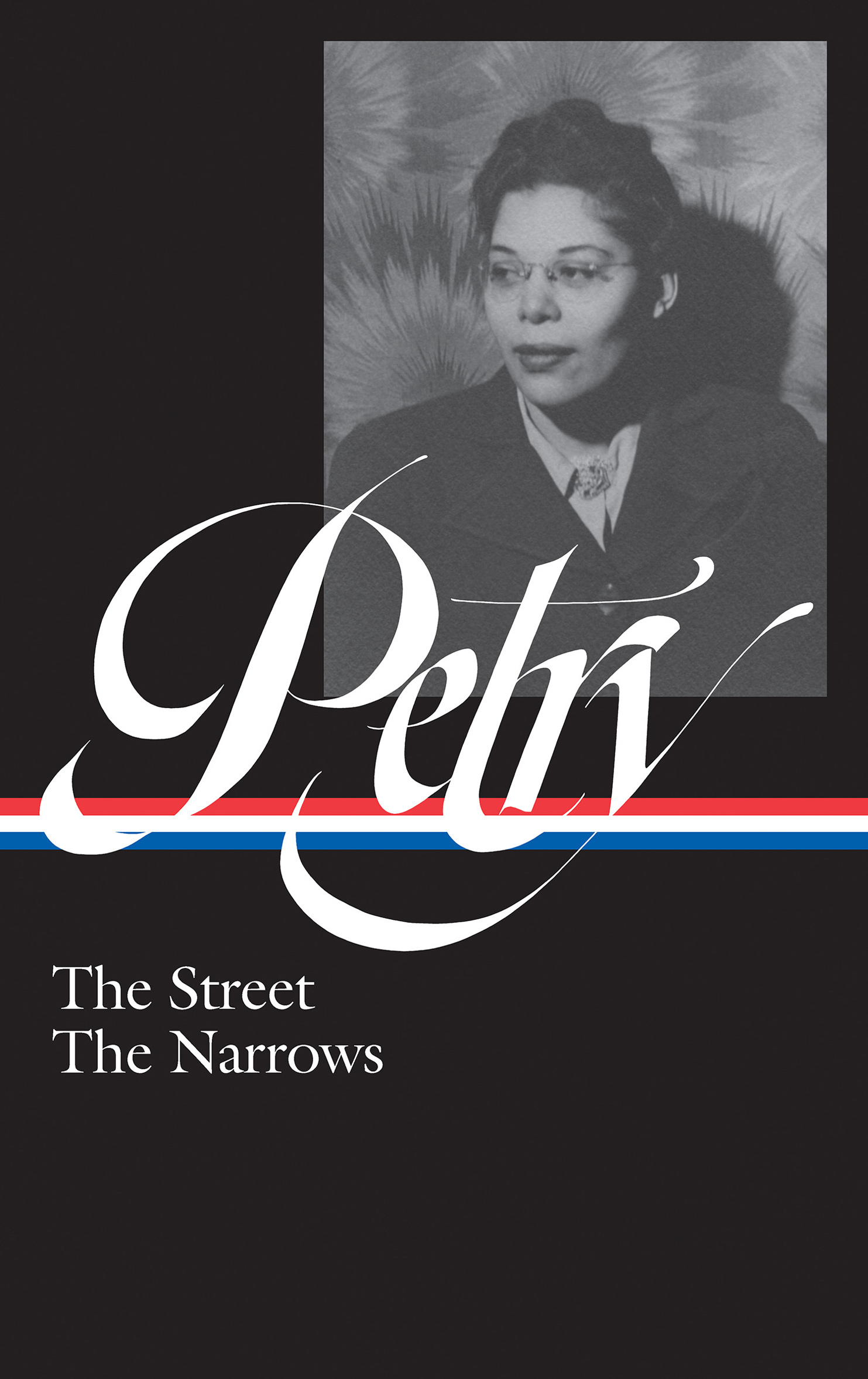

A NN P ETRY

THE STREET

THE NARROWS

Farah Jasmine Griffin, editor

LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

ANN PETRY: THE STREET, THE NARROWS

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

The Street copyright 1946, 1974 by Ann Petry. Published by arrangement

with Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

The Narrows copyright 1953, 1981 by Ann Petry. Harlem,

The Great Secret, and The Novel as Social Criticism

copyright 1949, 1950, 1977, 1978 by Ann Petry.

Published by arrangement with Elisabeth Petry.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of Americas best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors, and our popular

Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 9781598536027

Contents

The Street

To My Mother

BERTHA JAMES LANE

Chapter 1

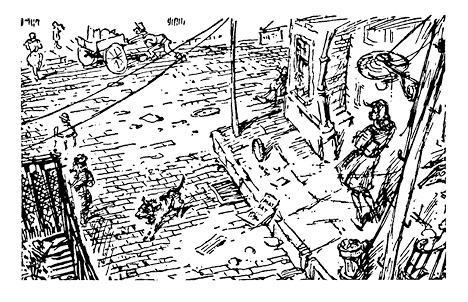

T HERE WAS A COLD November wind blowing through 116th Street. It rattled the tops of garbage cans, sucked window shades out through the top of opened windows and set them flapping back against the windows; and it drove most of the people off the street in the block between Seventh and Eighth Avenues except for a few hurried pedestrians who bent double in an effort to offer the least possible exposed surface to its violent assault.

It found every scrap of paper along the streettheater throwaways, announcements of dances and lodge meetings, the heavy waxed paper that loaves of bread had been wrapped in, the thinner waxed paper that had enclosed sandwiches, old envelopes, newspapers. Fingering its way along the curb, the wind set the bits of paper to dancing high in the air, so that a barrage of paper swirled into the faces of the people on the street. It even took time to rush into doorways and areaways and find chicken bones and pork-chop bones and pushed them along the curb.

It did everything it could to discourage the people walking along the street. It found all the dirt and dust and grime on the sidewalk and lifted it up so that the dirt got into their noses, making it difficult to breathe; the dust got into their eyes and blinded them; and the grit stung their skins. It wrapped newspaper around their feet entangling them until the people cursed deep in their throats, stamped their feet, kicked at the paper. The wind blew it back again and again until they were forced to stoop and dislodge the paper with their hands. And then the wind grabbed their hats, pried their scarves from around their necks, stuck its fingers inside their coat collars, blew their coats away from their bodies.

The wind lifted Lutie Johnsons hair away from the back of her neck so that she felt suddenly naked and bald, for her hair had been resting softly and warmly against her skin. She shivered as the cold fingers of the wind touched the back of her neck, explored the sides of her head. It even blew her eyelashes away from her eyes so that her eyeballs were bathed in a rush of coldness and she had to blink in order to read the words on the sign swaying back and forth over her head.

Each time she thought she had the sign in focus, the wind pushed it away from her so that she wasnt certain whether it said three rooms or two rooms. If it was three, why, she would go in and ask to see it, but if it said twowhy, there wasnt any point. Even with the wind twisting the sign away from her, she could see that it had been there for a long time because its original coat of white paint was streaked with rust where years of rain and snow had finally eaten the paint off down to the metal and the metal had slowly rusted, making a dark red stain like blood.

It was three rooms. The wind held it still for an instant in front of her and then swooped it away until it was standing at an impossible angle on the rod that suspended it from the building. She read it rapidly. Three rooms, steam heat, parquet floors, respectable tenants. Reasonable.

She looked at the outside of the building. Parquet floors here meant that the wood was so old and so discolored no amount of varnish or shellac would conceal the scars and the old scraped places, the years of dragging furniture across the floors, the hammer blows of time and children and drunks and dirty, slovenly women. Steam heat meant a rattling, clanging noise in radiators early in the morning and then a hissing that went on all day.

Respectable tenants in these houses where colored people were allowed to live included anyone who could pay the rent, so some of them would be drunk and loud-mouthed and quarrelsome; given to fits of depression when they would curse and cry violently, given to fits of equally violent elation. And, she thought, because the walls would be flimsy, why, the good people, the bad people, the children, the dogs, and the godawful smells would all be wrapped up together in one big packagethe package that was called respectable tenants.

The wind pried at the red skullcap on her head, and as though angered because it couldnt tear it loose from its firm anchorage of bobby pins, the wind blew a great cloud of dust and ashes and bits of paper into her face, her eyes, her nose. It smacked against her ears as though it were giving her a final, exasperated blow as proof of its displeasure in not being able to make her move on.

Lutie braced her body against the winds attack determined to finish thinking about the apartment before she went in to look at it. Reasonablenow that could mean almost anything. On Eighth Avenue it meant tenementsghastly places not fit for humans. On St. Nicholas Avenue it meant high rents for small apartments; and on Seventh Avenue it meant great big apartments where you had to take in roomers in order to pay the rent. On this street it could mean almost anything.

She turned and faced the wind in order to estimate the street. The buildings were old with small slit-like windows, which meant the rooms were small and dark. In a street running in this direction there wouldnt be any sunlight in the apartments. Not ever. It would be hot as hell in summer and cold in winter. Reasonable here in this dark, crowded street ought to be about twenty-eight dollars, provided it was on a top floor.

The hallways here would be dark and narrow. Then she shrugged her shoulders, for getting an apartment where she and Bub would be alone was more important than dark hallways. The thing that really mattered was getting away from Pop and his raddled women, and anything was better than that. Dark hallways, dirty stairs, even roaches on the walls. Anything. Anything. Anything.