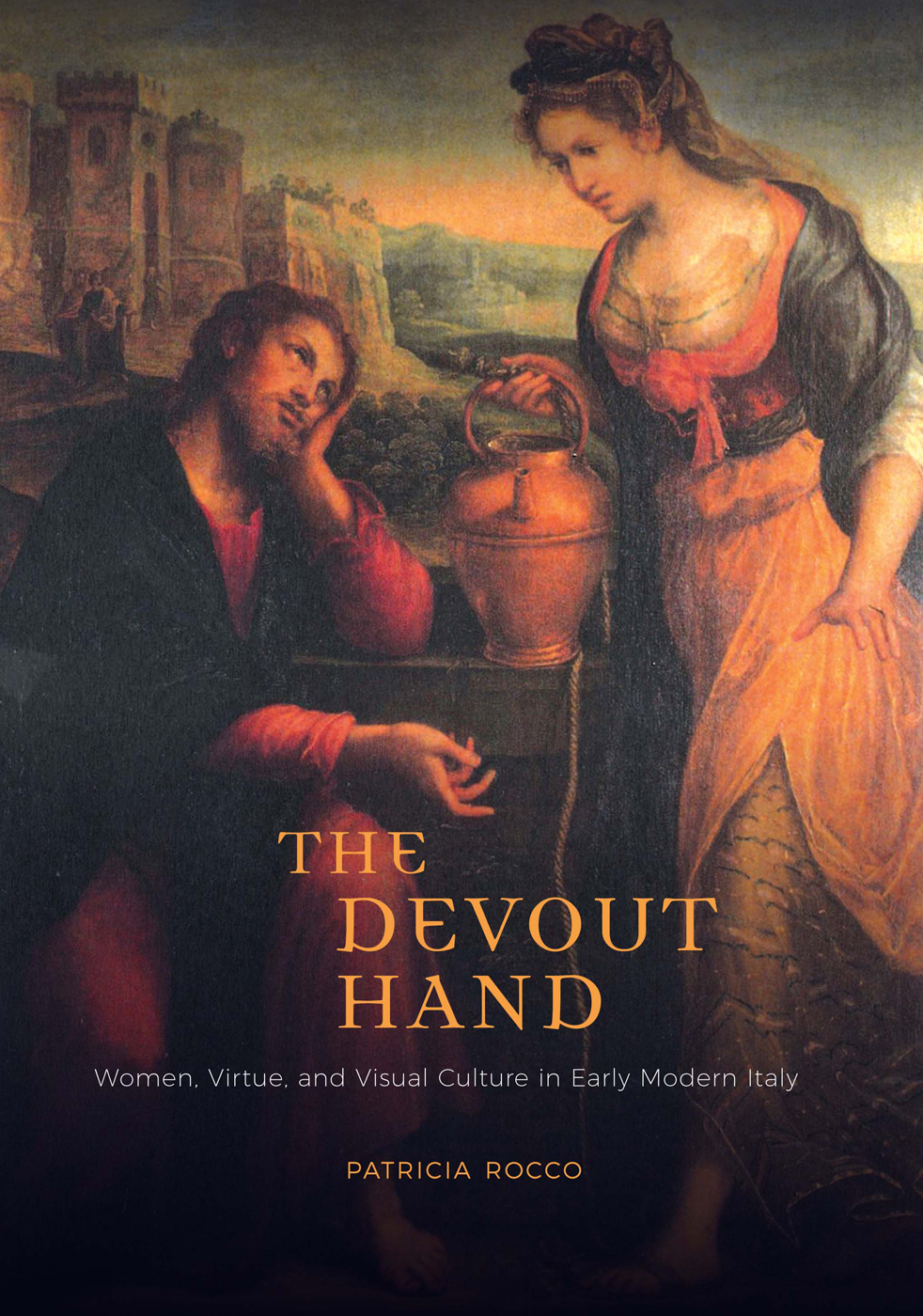

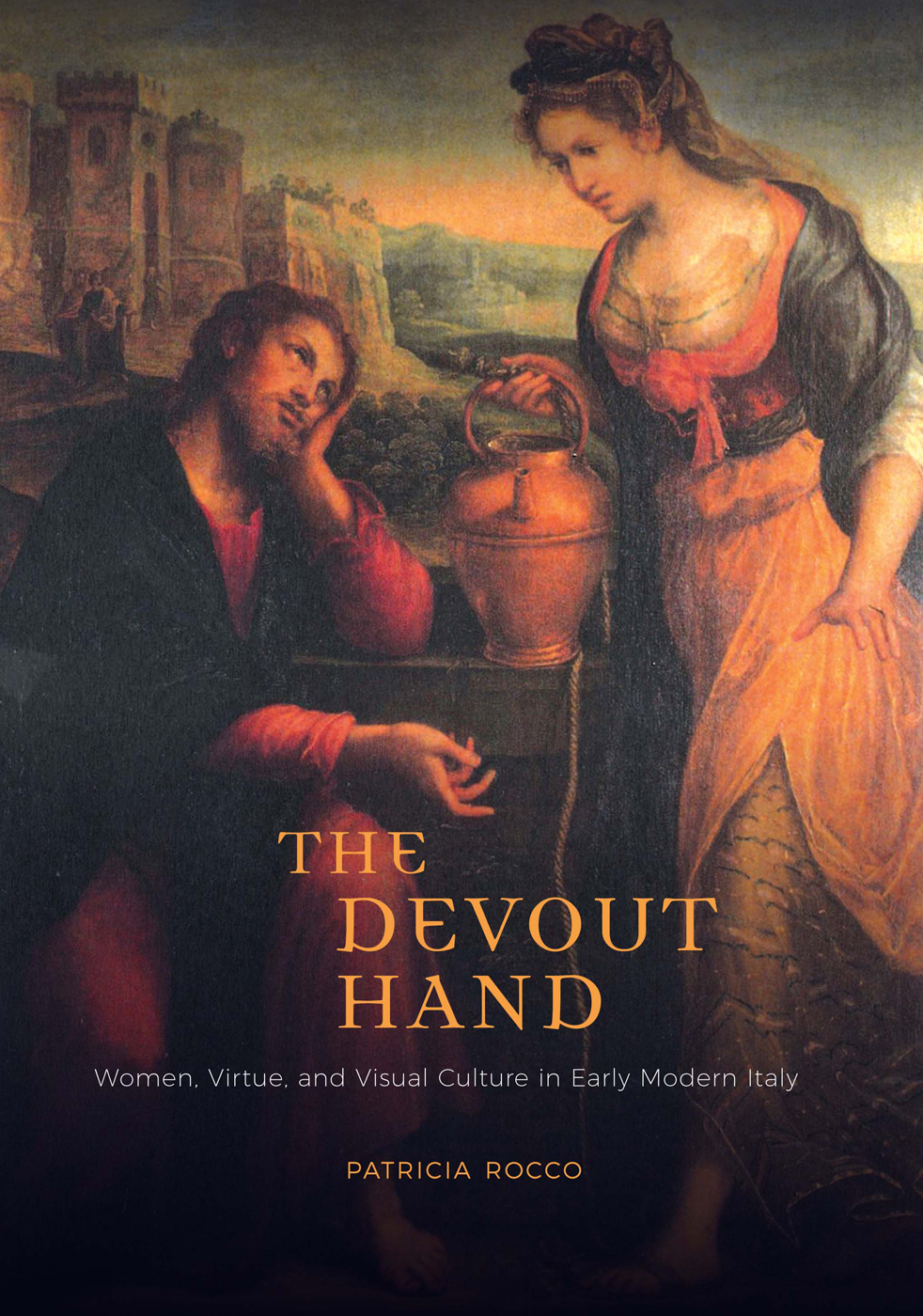

THE

DEVOUT HAND

THE

DEVOUT HAND

Women, Virtue, and Visual Culture in Early Modern Italy

PATRICIA ROCCO

McGill-Queens University Press

Montreal & Kingston London Chicago

McGill-Queens University Press 2017

ISBN 978-0-7735-5138-1 (cloth)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5219-7 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-0-7735-5220-3 (ePUB)

Legal deposit fourth quarter 2017

Bibliothque nationale du Qubec

Printed in Canada on acid-free paper

McGill-Queens University Press acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Rocco, Patricia B., 1967, author

The devout hand : women, virtue, and visual culture in early modern Italy / Patricia B. Rocco.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-7735-5138-1 (hardcover).ISBN 978-0-7735-5219-7 (ePDF).ISBN 978-0-7735-5220-3 (ePUB)

1. Art, ItalianItalyBologna16th century. 2. Art, ItalianItalyBologna17th century. 3. Women artistsItalyBolognaHistory16th century. 4. Women artistsItalyBolognaHistory17th century. 5. Bologna (Italy)Intellectual life16th century. 6. Bologna (Italy)Intellectual life17th century. 7. Women artistsItalyBolognaIntellectual life16th century. 8. Women artistsItalyBolognaIntellectual life17th century. 9. Bologna (Italy)HistoryPapal rule, 1506-1797. I. Title.

N6921.B7R63 2017 | 709.454110903 | C2017-904250-5 C2017-904251-3 |

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

FIGURES

FIGURES

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book is dedicated to my parents, Giovanni and Gilda, as a token of gratitude for their love, and in appreciation of the cultural heritage they passed on to me; to my husband, Erik, whose tireless dedication helped make this book possible; to the professors who mentored me at the Graduate Center CUNY: James Saslow, Elinor Richter, and Barbara Lane, and to my colleagues and friends there for their constant encouragement; to Bronwen Wilson at McGill University, who awoke in me a desire to study the material and visual culture of Renaissance Italy, and to those excellent scholars whose work inspired my interest in the women artists of the early modern period: to name but a few, Adelina Modesti, Vera Fortunati, Maria Teresa Cantaro, and Caroline Murphy. A special thanks goes to my editor, Kyla Madden, whose support in this project was invaluable, and to all the excellent staff at MQUP for their help in making this book a reality. Many thanks also go to the institutions and individuals who kindly gave me permission to reproduce the great works in their collections, galleries, museums, and churches. Last but not least, this book is dedicated to the mani donnesche of Bologna, the women artists and the girls of the conservatori, whose work I hope to bring alive in such a way that the tangibility of this visual culture may help them achieve a glimmer of immortality.

THE

DEVOUT HAND

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

It has long been evident in modern scholarship that womens participation in religious movements during the Early Modern period in Europe has received less comment than that of their male counterparts. With this book I hope to deepen our understanding of the role of women in the visual program of the Counter-Reformation in the Papal State of Bologna. I focus on Bologna because, as well as being a crucial site of Catholic reform, that city had an unprecedentedly large group of active women artists. However, knowledge of Bolognas women artists is still incomplete. What follows is therefore a series of interlinked case studies, some of which rescue forgotten artists, while others add new dimensions to better-known figures. This project takes a necessarily broad approach, combining aspects of iconography, patronage, gender studies, and reception studies; it also integrates media such as prints and embroidery, which have been underrepresented in previous studies.

To set Bolognas women artists in the philosophical and theoretical context of the citys intellectual history, I first investigate contemporary links between religion, science, and naturalism and then go on to unpack critical terms from the historiography of style that have come to bear on their work. Lastly, I explore Bolognas concern with womens virtue, a constant theme in the visual imagery of all media from the sixteenth into the seventeenth century. The synthesis of all this material offers a wider view of the still-understudied and ill-documented relationship between women, religion, and the visual arts in the complex period of the Counter-Reformation.

Fig. i.1. Lavinia Fontana, Self-Portrait, 1577. Oil on canvas. 27 24 cm. Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Galleria Accademica. Fontanas self-portrait was created for her marriage to Gian Paolo Zappi; however, she makes sure to include her easel in the background. Image reproduced courtesy of Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Roma.

Although this style was in decline by the mid-sixteenth century, the Counter-Reformation, pursuant to the Council of Trent (154563), brought a renewed interest in the maniera devota, and the women of Bologna were actively involved in its use and reception.

The term mano donnesca derives from sixteenth- and seventeenth-century art criticism relating to the gendered hand of the artists style. The term has traditionally been used in a pejorative sense to denote a style that was overly laboured, especially in regard to minute surface detail, and was thus considered appropriate only to female artists who, in the hierarchy of genres, were usually relegated to portraiture. However, such a reading of the term is limiting. The then powerful archbishop Gabriele Paleotti (15221597) encouraged women artists to take an active role in the Counter-Reformation movement to renew Christian imagery. Paleottis approach created a dialogue between maniera devota and mano donnesca in which gender both influenced the production of sacred visual culture and was, in turn, affected by it.

Early modern Bologna was unique in having several prodigious female artists, some of whom had been lost to modern art criticism until very recently, despite the fame they had attained during their lifetimes. The career of Lavinia Fontana (15521614;

Fig. i.2. Elisabetta Sirani, Self-Portrait, 1658. Oil on canvas. 114 85 cm. Moscow, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Siranis self-portrait stresses her learned education, and is meant to evoke the artist as the allegory of painting. Image reproduced courtesy of Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Paleotti wrote the definitive work on the reformation of images, Discorso intorno alle immagini sacre e profane, published in 1582. The Discorso enjoined artists to create clear visual imagery with a didactic purpose, promoting naturalism in reaction to mannerist excesses. Paleotti also called for womens participation in religious reform, thereby endowing women in Bologna with greater agency than elsewhere and producing opportunities for the first successful group of women artists. This attitude was in marked contrast to that prevalent in cities such as Florence, whose visual imagery in the late sixteenth century bears primarily the stamp of a more male-dominated ducal iconography. Paleottis far-reaching reforms also included promoting charitable institutions for the religious education and reform of young girls and wayward women. In turn, these institutions required new religious images with specific iconography tailored to their site, its functions, and its audience, works such as the embroidered copies of altarpieces by Fontana and Sirani created by women in these reform houses.

Next page

CONTENTS

CONTENTS