For my wife, Bernadette, and our children, Alexander, Charlotte, and Sebastianreaders every one.

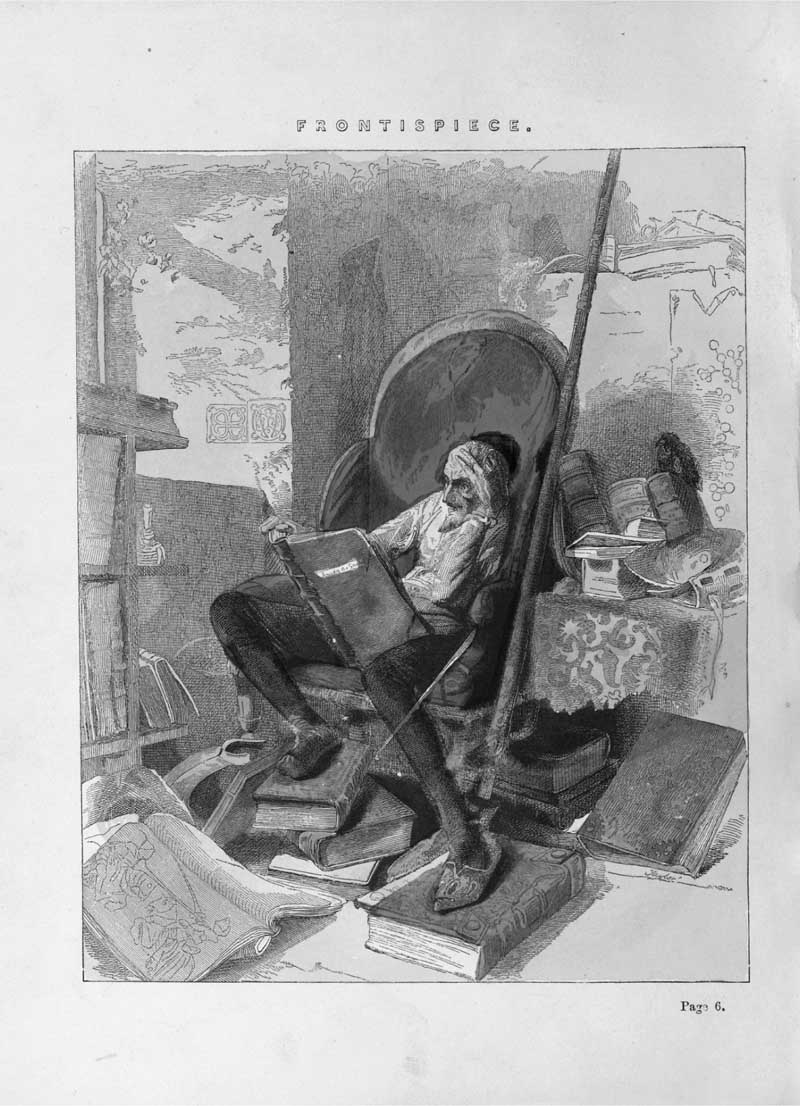

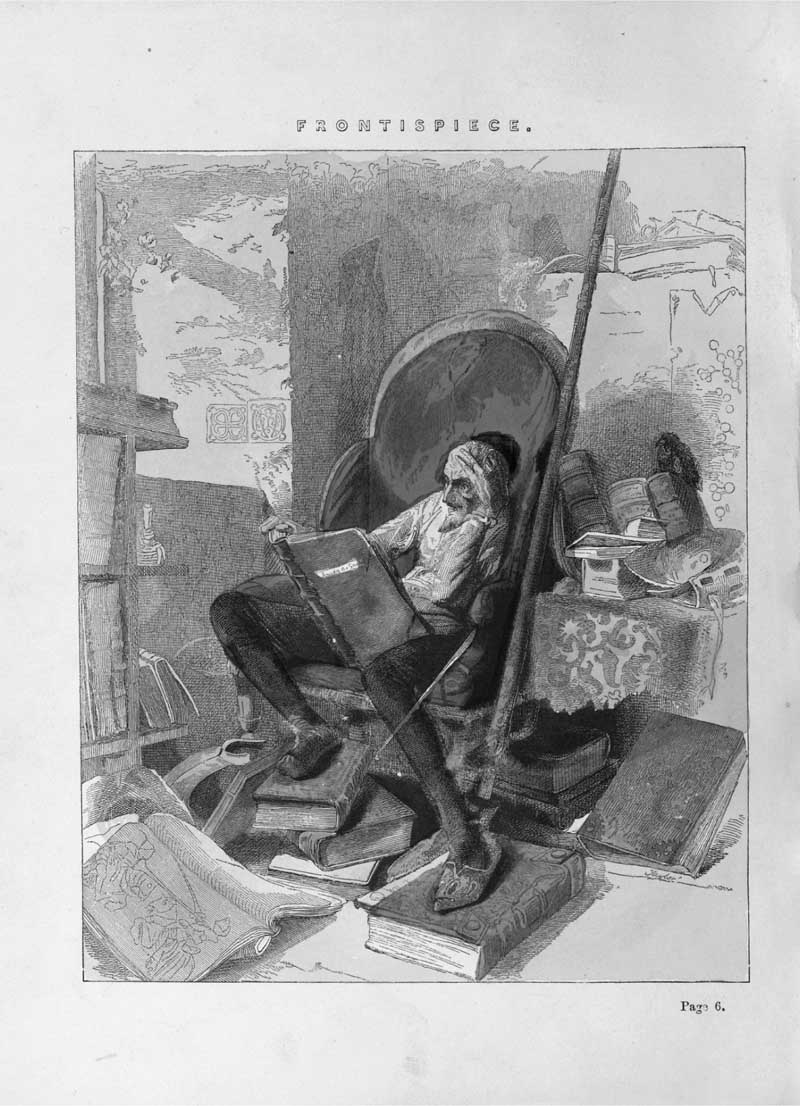

Sir Marvellous Crackjoke , with illustrations by Kenny Meadows and John Gilbert, The Wonderful Adventures of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza Adapted for Youthful Readers . London: Dean & Son, 1872. George Peabody Library, the Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

CONTENTS

Something strange happened in the winter of 1605. At the heart of the worlds most powerful empire, in a time of economic decline and political stagnation, word started spreading about, of all things, a book. The dealers quickly sold out; those who could read passed increasingly threadbare copies from hand to hand; and those who could not read began to congregate in inns, village squares, and taverns to hear the pages read aloud.

Packed in tightly around worn wooden tables, clutching goblets of acrid wine and warmed by a smoky hearth, those fortunate enough to be in attendance when a literate benefactor declaimed the opening words were not treated to an epic rendering of heroic deeds, a lyrical paean to a shepherds love, or a pious reflection on the martyrdom of a beloved saint. Instead, as they washed back their dregs and squeezed in closer to get a better seat, they were among the first to hear these now immortal opening words: Somewhere in La Mancha, in a place whose name I do not care to remember, a gentleman lived not long ago

It would not be long until the tipsy crowd was cackling in delight over the misadventures of what would become world literatures most recognizable protagonist: a rickety, geriatric member of the lower gentry who, foolish enough to have traded in much of his land for countless books of chivalry, became so caught up in reading that he spent his nights reading from dusk till dawn and his days reading from sunrise to sunset, and so with too little sleep and too much reading his brains dried up, causing him to lose his mind. In this state the pitiful gentleman has

the strangest thought any lunatic in the world ever had, which was that it seemed reasonable and necessary for him, both for the sake of his honor and as a service to the nation, to become a knight errant and travel the world with his armor and his horse to seek adventures and engage in everything he had heard that knights errant engaged in, righting all manner of wrong and, by seizing the opportunity and placing himself in danger and righting those wrongs, winning eternal renown and everlasting fame.

How they howled with laughter as they heard for the first time the exploits of this ridiculous geezer wandering a countryside they recognized as their own, and coming face-to-face with the kinds of people they spent their days with, the kinds of people they were likely rubbing shoulders with as they listened to his tale: mule drivers and scullery maids, farmers and prostitutes, barbers and innkeepers.

For the first half hour our tavern crowd is treated to the circus it came for: the aging madman mistakes a shabby inn for a castle, its owner for a noble knight, and two common wenches for exquisite ladies. He requests the boon of an official dubbing from the wily innkeeper, who knows his tales of chivalry enough to keep in character even as the hapless hero wreaks havoc on the innkeepers guests and provokes giggles in the ladies of easy virtue. And he chastises a farmer for beating his servant, but then trusts in his chivalry enough to send them off again together with a mere promise of recompense, to the farmers sly delight and the servants enduring agony. The story that our tavern crowd is hearing is pure and bawdy satire, an unbridled ribbing of an impoverished and degenerate gentry anaesthetized by the clichd literature of a previous century.

Well into their second or third round of libations, our tavern goers hear how the aged gentleman comes to realize he is missing something, and resolves to return to his house and outfit himself with everything, including a squire, thinking he would take on a neighbor of his, a peasant who was poor and had children but was very well suited to the chivalric occupation of a squire. At home for two weeks, the delusional knight convinces his peasant neighbor to join him, promising him upon completion of their quest an islandwhich he insists on calling, in proper epic form, by its Latinate name, an insula insouciant to the geographically inconvenient fact that they are wandering around the arid plains of central Spain, many days travel from any significant body of water.

The introduction of this stout, simple neighbor changes everythingfor the listeners in the tavern and for us, their literary descendants. Until Don Quixote seeks out Sancho Panza (for these, of course, are the characters I have been describing), he is but a foil, a rubea brilliantly crafted one, for sure, but nonetheless an object of derision that our tavern fellows would feel comfortable ridiculing. At the time, the mentally ill were protected from prosecution from certain crimes, but they were not protected from abuse, marginalization, or being used as the butt of the joke for a populace starved for entertainment. Having found Sancho Panza, though, Quixote suddenly becomes something quite different.

Within a page or two of setting off together, the two companions encounter their most iconic adventure:

Good fortune is guiding our affairs better than we could have desired, for there you see, friend Sancho Panza, thirty or more enormous giants with whom I intend to do battle and whose lives I intend to take, and with the spoils we shall begin to grow rich, for this is righteous warfare, and it is a great service to God to remove so evil a breed from the face of the earth.

What giants? said Sancho Panza.

Those over there, replies his master, with the long arms; sometimes they are almost two leagues long.

Look, your grace, Sancho responded, those things that appear over there arent giants but windmills, and what looks like their arms are the sails that are turned by the wind and make the grindstone move.

Predictably, famously, Don Quixote does not heed his good squires commonsense admonitions, but instead charges ahead, spearing the enormous sail of a windmills arm with his lance and being lifted, horse and all, off the ground and smashed back down in a miserable, aching heap. Sanchos reaction to his mishap, though, is different from those that greeted all Quixotes previous antics. Where the others treated Quixote as a spectacle, entertainment, or a nuisance, Sancho responds with compassion. Seeing his master lying next to his fallen horse and shattered lance, Sancho

hurried to help him as fast as his donkey could carry him, and when he reached them he discovered that Don Quixote could not move because he had taken so hard a fall with Rocinante.

God save me! said Sancho. Didnt I tell your grace to watch what you were doing, that these were nothing but windmills, and only somebody whose head was full of them wouldnt know that?

From the limited outlook of his own simplicity, Sancho sees his master fail, sees the calamitous consequences of his delusions, and yet decides to accept him despite them: Its in Gods hand, said Sancho. I believe everything your grace says, but sit a little straighter, it looks like youre tilting, it must be from the battering you took when you fell.

In the space of a few pages, what started as an exercise in comic ridicule and, as the narrator insists on several occasions, a satirical send-up of the tales of chivalry, has taken on an entirely different dimension; it has begun to transform itself into the story of a relationship between two characters whose incompatible takes on the world are bridged by friendship, loyalty, and eventually love. When deep in the second part (published ten years after the first) a mischievous duchess elicits Sanchos confession that he does indeed know that Quixote is mad, and then accuses him of being more of a madman and dimwit than his master for following him, Sancho replies:

Next page