To H:

For reminding me whats most important.

And to A, J, and K:

For being whats most important. Asannittumik.

Copyright 2017 by David Welky

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Lisa Buckley

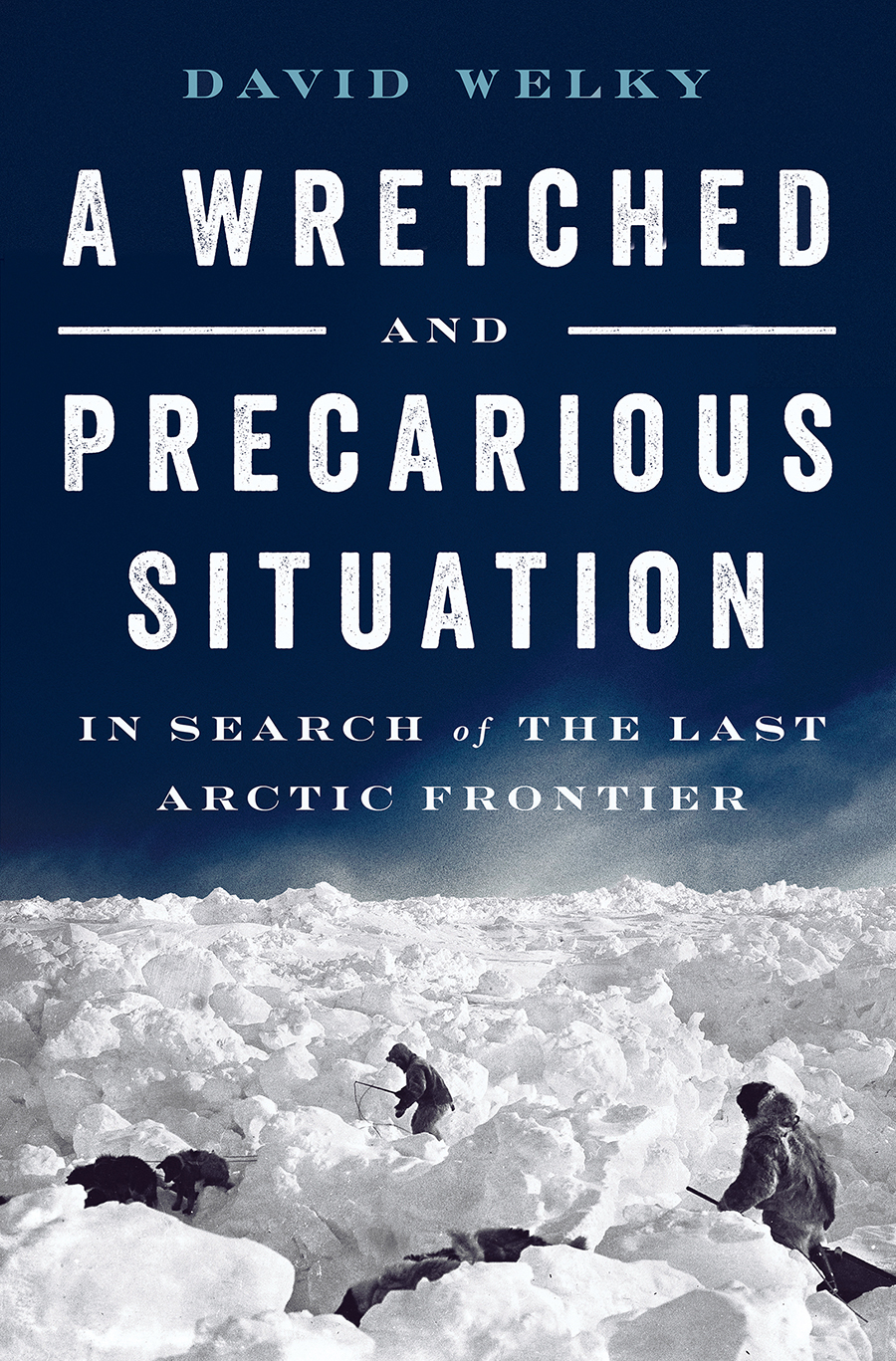

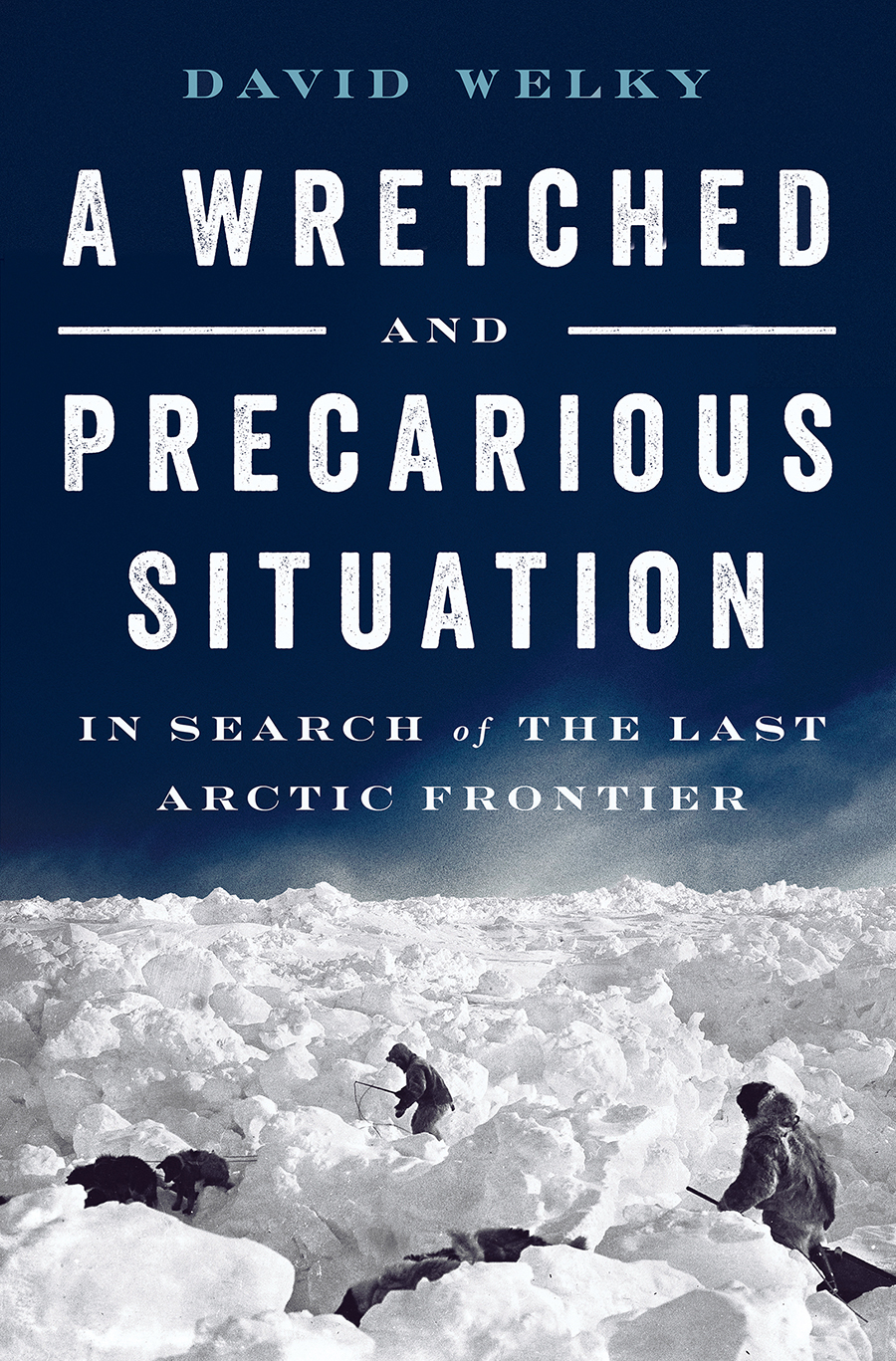

Jacket design by Pete Garceau

Jacket photograph: Image# 233094, American Museum of Natural History Library

Production manager: Anna Oler

ISBN 978-0-393-25441-9

ISBN 978-0-393-25442-6 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.,

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

Not here: The White North hath thy bones;

And thou, heroic sailor-soul,

Art passing on thine happier voyage now

Toward no earthly pole.

Alfred, Lord Tennyson,

epitaph for Rear Admiral Sir John Franklin, Arctic explorer

A NOTE ON NAMES

AND WORDS

ONE OF THE GREAT CHALLENGES of writing about the far north is figuring out who you are writing about. The Polar Inuit tribe of northwest Greenland had no written language at the time of the Crocker Land expedition. Visiting Westerners who transcribed what they heard therefore recorded many variants of a single persons name. To give but one example, a man named Qisuk appears in explorers notes as Kishu, Kissuk, Kessuh, Kubliknik, Qissuk, and Kusshan. When reading multiple accounts from the same time period, it becomes easy for a historian to inadvertently combine two people with similar names into one person, or to turn a single person into two or more people.

Throughout A Wretched and Precarious Situation, I have done my best to regularize the names of members of the Polar Inuit tribe, also known as the Inughuit (Inuk means person and Inughuit means people) in accordance with current official Greenlandic orthography. Except for a few clearly marked points in the text, I have silently modified names appearing in quoted material to conform with proper spellings. I have done the same with Inuktun words (Inuktun is the language of the Inughuit), again with a few exceptions. To avoid confusion, I use the conventional kayak instead of qajaq. The settlement of Iita has been consistently referred to as Etah for more than a century, so I have again opted for the westernized spelling. Finally, I have changed the plural form of some Inuktun words for the sake of Western sensibilities. The plural of qamutit (sledge), for example, is also qamutit, but I have added an s for ease of reading. The word kamik (boot) has two plurals: kamiik (a pair of boots), and kamiit (three or more boots). Instead of having people put a kamiik on their feet, I use kamiks when referring to multiple boots, despite it being grammatically incorrect.

MINE BY THE RIGHT

OF DISCOVERY

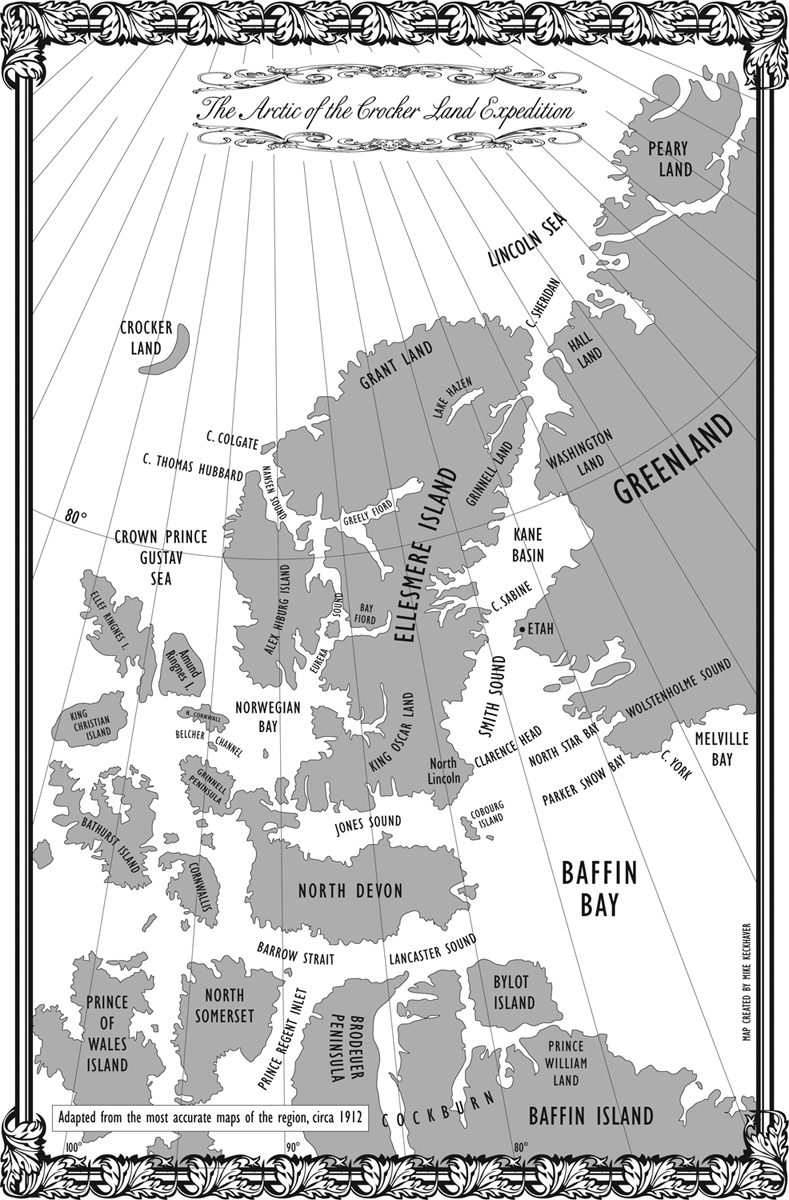

APRIL 21, 1906. NAVY COMMANDER Robert E. Peary, the worlds most famous explorer, had failed again.

An uninformed observer might disagree. Swaddled in furs against temperatures that sometimes reached 60 degrees Fahrenheit even when the wind was calm, as it was today, Peary appeared confident as he strode across the thick ice encrusting the polar sea. His most recent navigational sightings told him that he was standing at 87 6 north latitude. At that moment he and his men were more than the northernmost people on the planet; they were farther north than any humans had ever been.

Peary was in the ultimate no mans land. The nearest piece of solid ground lay over 350 miles to the south. His goal, the North Pole, lay 174 nautical miles in front of him, roughly the distance from Boston to New Yorkhalf again as far as he had already traveled.frozen surface. Over the past few decades he had earned a well-deserved reputation as the most determined, the most resourceful, and the most gifted leader in the history of Arctic exploration. If there was any way to get to the top of the Earth, he was the man to do it.

Then again, the travails the explorer had endured on his way to 87 6 would have killed an uninformed observer. Peary envisioned nature as a relentless, almost demonic foe bent on thwarting his dreams. On this frigid morning, four and a half years into Theodore Roosevelts presidency and eight years before the phrase world war had any real meaning, the enemy had defeated him again.

Pearys men had suffered a series of delays during their six weeks on the polar sea. One hundred miles out, after days of battering their sledges into unforgiving walls of uneven ice, the team had encountered a wide band of open water, called a lead, slashing across their path. Although common, leads were one of the great banes of dogsled travel. Native drivers prodded east and west for a way around but found no solid ice. No matter how much the commander stomped and fumed, he could not cross what he called the river Styx until that mythological boundary of Hades literally froze over.

Peary was losing the Pole. His entire campaign relied on his precise calculations of weight, distance, and time. Sled dogs could haul only so much food and vital equipment such as stoves and alcohol fuel. There was no hope of resupply this far out. Peary had set off with a large party and sledges packed full of supplies. Members sacrificed themselves for the good of the mission, consuming the supplies they carried until they were forced to peel away from the main group and return to safety. Having ensured Pearys further progress toward ninety north, their job was complete and they were expendable. But no amount of planning could restrain the seasons. Every day wasted before the river Styx increased the chance that climbing temperatures would break up the ice, stranding and eventually drowning the expedition. It was a paradox unfamiliar to other Americans: warmth meant death.

The men waited for an excruciating week before a rubbery strip of new ice created a bridge over the Styx. Not long after the crossing, the frustrated commander called another halt when the weather turned rotten. More precious days slipped away while the hell-born music of an Arctic blizzard battered the forlorn camp.

Peary then ran headlong into a maze of jagged rafters, the huge piles of ice heaved skyward when currents drove massive floes together in an aquatic version of the tectonic collisions that created mountain chains. The men muscled their sledges, or qamutits, over miles of frozen chaos. Inch by inch they pushed and pulled, often slowing their pace to a literal crawl as they nudged northward.

Each degree of latitude exacted a greater emotional and physical toll. Exhaustion marked the teams wind-scarred faces. Even the heartiest among them looked half dead. Frostbite blotched Pearys left cheek. Agonizing blisters enveloped his feet. His toeseight of them mere stumps, having been amputated seven years previously because of frostbite throbbed with pain. Food was running low.

The dogs whined with hunger. Peary had the six weakest ones killed and fed to the others. There was no game within 300 miles, no walruses or seals or caribou, so starvation would certainly claim more of the beasts. Fewer dogs meant slower travel, and slower travel meant death. The natives muttered doubts about ever seeing their families again.

Next page