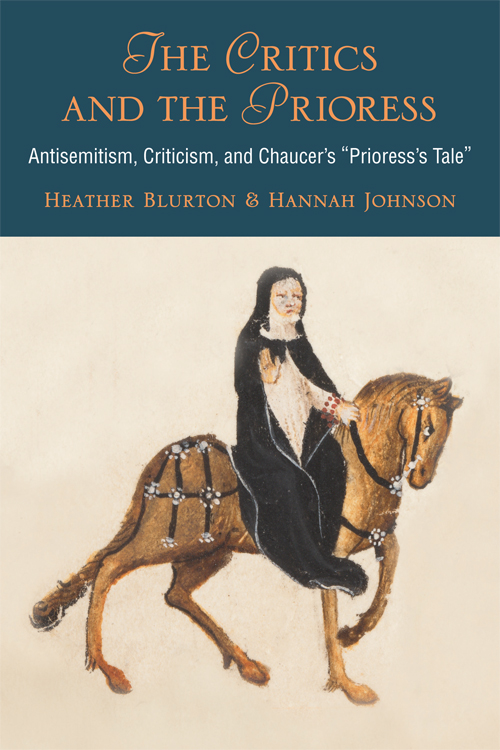

The Critics and the Prioress

The Critics and the Prioress

Antisemitism, Criticism, and Chaucers Prioresss Tale

Heather Blurton and Hannah Johnson

University of Michigan Press

Ann Arbor

Copyright by the University of Michigan 2017

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher.

Published in the United States of America by the

University of Michigan Press

Manufactured in the United States of America

A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Blurton, Heather, author. | Johnson, Hannah R., 1974 author.

Title: The critics and the prioress : antisemitism, criticism, and Chaucers Prioresss tale / Heather Blurton and Hannah Johnson.

Description: Ann Arbor : University of Michigan Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016045207| ISBN 9780472130344 (hardback : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780472122813 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Chaucer, Geoffrey, 1400. Prioresss tale. | Antisemitism in literature. | BISAC: LITERARY CRITICISM / Ancient & Classical.

Classification: LCC PR1868.P73 B87 2017 | DDC 821/.1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016045207

For Isaac

Contents

This project had its origin in conversations we had as Visiting Fellows at the Obermann Center for Advanced Studies at the University of Iowa along with Kathy Lavezzo in 2011. We thank the Obermann Center, and particularly Kathy Lavezzo, for the stimulating environment and the discussions we had there. We are grateful to the American Council of Learned Societies for a Collaborative Research Fellowship in 201314, which enabled us to complete much of the research and writing for this book, and to Anthony Bale and Lisa Lampert-Weissig for writing in support of our application. For their unflagging generosity in reading various drafts of these chapters, and especially for their tough-minded and extremely helpful advice, we owe a great debt to Lisa Lampert-Weissig and Kathy Lavezzo. Audiences at the University of California, Riverside; the Nineteenth Biennial International Congress of the New Chaucer Society in Reykjavik, Iceland; and the Networks and Neighbors Colloquium at the University of California, Santa Barbara heard early drafts and contributed thoughtful comments and suggestions. Steven Justice and an anonymous reader for the University of Michigan Press provided perceptive readings and discerning advice that enabled us to return to the project with fresh eyes. A version of the fourth chapter appeared as Reading the Prioresss Tale in the Fifteenth Century: Lydgate, Hoccleve and Marian Devotion, in the Chaucer Review 50 (2015). Another article is included in revised form as part of chapter 1: Hannah R. Johnson, Antisemitism and The Purposes of Historicism: Chaucers Prioresss Tale in Middle English Literature: Criticism and Debate, ed. D. Vance Smith and Holly Crocker (New York: Routledge, 2014), 192200. We thank the publishers for permission to reproduce this material. And, of course, we remain grateful as ever to Brian Donnelly and Stuart Braun for their support, encouragement, and pancakes. With such an illustrious group of supporters, it goes without saying that all errors and opinions remain our own.

Whan seyd was al this miracle, every man

As sobre was that wonder was to se

When the Prioress finishes her tale, the pilgrims response is silence. To break the sober moment, the Host begins to jape. Turning to Chaucer, he asks, what man artow? and requests a tale of mirth. Chaucer, that is, the character of Chaucer who appears among the pilgrims company in the Canterbury Tales, launches into the Tale of Sir Thopas, a tale of myrthe and of solas / Al of a knight was fair and gent. The Host, however, finds neither mirth nor solace in this tale, and cuts Chaucer short, requesting some mirth or some doctrine. Chaucer replies, in prose, with a moral tale virtuous, The Tale of Melibee. Accordingly, the Prioresss Tale is one of a series of tales that plays with the destabilized and destabilizing properties of language itself. Thus, in Peter Traviss words:

the ice-cold uncomedy of the Shipmans fabliau; the spiritual ferocities of the Prioresss boy martyrology; the narrative and prosodic pratfalls of Chaucers Sir Thopas; the monitory confusion of a thousand proverbs

This seems an apt characterization, and in this light, the sober reaction of the pilgrims to the Prioresss Tale functions as a sort of mise en abyme in an already incredibly self-reflexive work, where narrative itself pauses, for a moment, to reconsider.

But this pause also introduces a critical conundrum. The pilgrims sober response to the Prioresss Tale and the crisis of narrative that ensues have puzzled critics, who have struggled with the question of what it would mean to read it straight or askew. Is the audiences sobriety an appropriately worshipful and respectful response to a religious tale told by a nun? Or is their sobriety an indication that they are uncomfortably taken aback by the tales demonizing of its Jewish figures? The pilgrims, with their ambiguous response, stand as a kind of cipher for the terse economy of the tale itself. Is its impact primarily devotional or satirical? Does the tale comment on its teller, or reflect the culture that produced her? Does Chaucer surpass his contemporaries and transcend his moment, or produce an excellent exemplar of a predictable genre? None of these questions is untouched by the others, and concerning all of them, we find settled areas of dispute resounding with broadly similar arguments offered over the course of the past century or so.

The Prioresss Tale offers a narrative that, by any measure, already contains much that is askew by modern standards. The Prioress recounts the story of a young boy who is so devoted to the Virgin Mary that he continuously practices singing a hymn in her honor as he walks back and forth to school. His path takes him through the Jewish quarter of his town, where his incessant singing so provokes the Jews that they hire a killer to slit the boys throat and toss him in the sewer. However, his singing continues unabated even in death, enabling his bereaved mother to discover both his body and the conspirators. The Jews judged responsible are subsequently executed, and the boy is buried with honor in the local abbey. Despite the spare limits of Chaucers Prioresss Tale, as Hannah Johnson has noted elsewhere, even its glancing details now have a critical history of their ownthe tales setting in a greet cite, located in Asie rather than in England (488)... the sentimental diminutives that distinguish the Prioresss Long after the death of the author, these ghosts in the Chaucerian machine continue to polarize critics who are concerned about the poems ethical implications.

The problem of ambiguity in reception has erupted out of the Canterbury frame, one might say, to become a problem for understanding the tales intended or likely impact among Chaucers readers. Indeed, the tale has come to focus a series of questions related to Chaucers own ethical and authorial positioning. Despite a number of efforts to rehabilitate Chaucer on the grounds of satire, suggesting that he was mocking the Prioress and, by extension, her antisemitism with his tale, critics like Derek Pearsall and Emily Stark Zitter voice another commonly held view when they find him guilty of a regrettable but historically comprehensible ethical failing.about the tales ethical implications, and the authors implication in them. Over the past fifty years, in particular, scholars have asked whether the antisemitism in the tale is that of the Prioress, or of Chaucer the pilgrim, or of Chaucer the authoror, indeed, whether one ought to discuss antisemitism in the

Next page